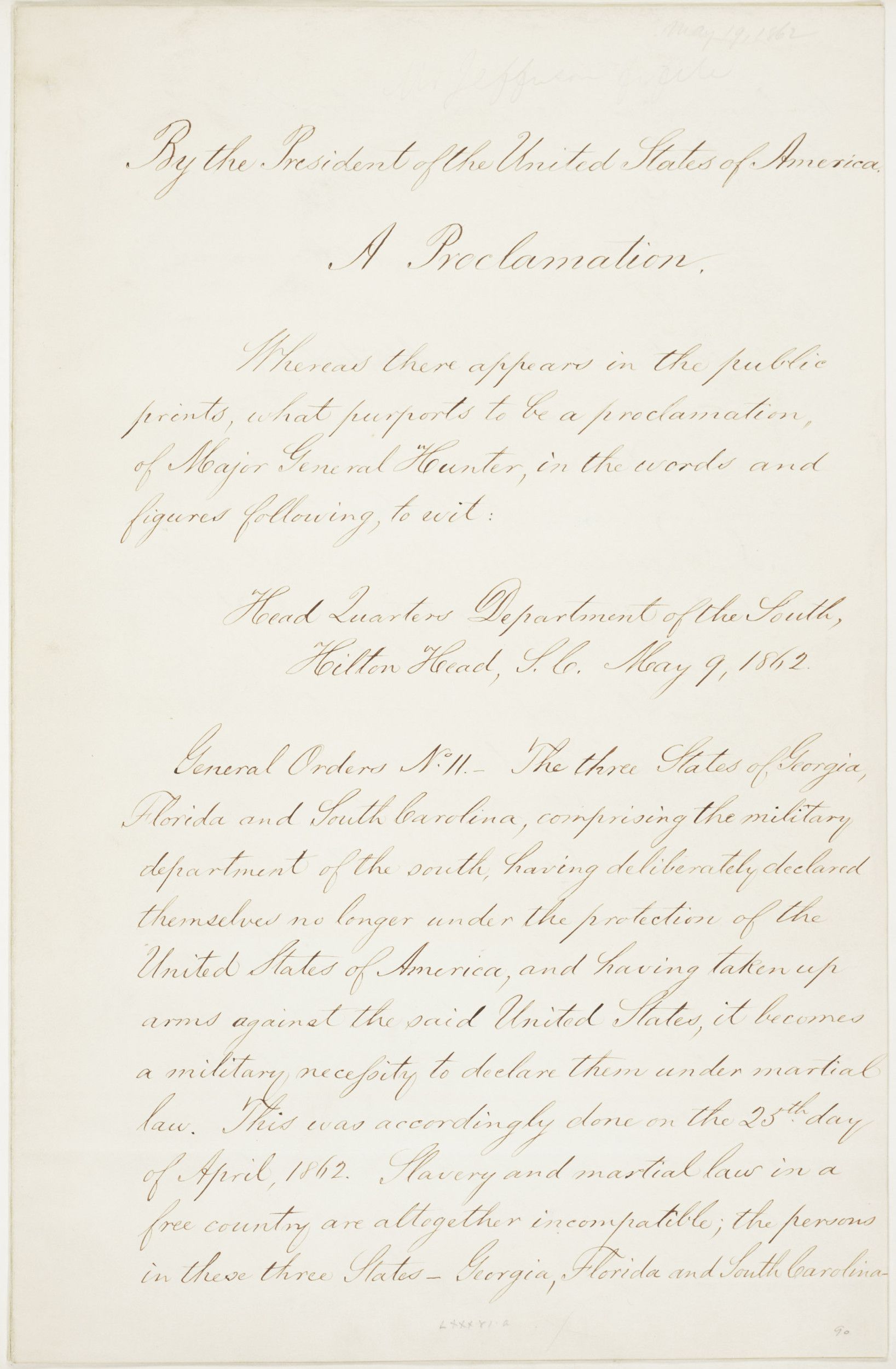

Presidential Proclamation 90 by President Abraham Lincoln Revoking General David Hunter's Order of Military Emancipation

5/19/1862

Add to Favorites:

Add all page(s) of this document to activity:

Add only page 1 to activity:

Add only page 2 to activity:

Add only page 3 to activity:

Add only page 4 to activity:

Add only page 5 to activity:

Additional details from our exhibits and publications

On May 9, 1862, Gen. David Hunter declared all slaves in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida “forever free” and authorized them to serve in the U.S. Army. President Lincoln believed only he could give such an order. Twelve days later he issued this proclamation revoking Hunter’s edict. He scolded the general for exceeding his authority but warned slaveholders that such an order might “become a necessity indispensable to the maintenance of the government.”

Transcript

By the President of the United States of America

A Proclamation

A Proclamation

Whereas there appears in the public prints, what purports to be a proclamation of Major General Hunter, in the words and figures following, to wit:

Head Quarters Department of the South,

Hilton Head, S.C. May 9 1862

General Orders No 11._ The three States of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, comprising the military department of the south, having deliberately declared themselves no longer under the protection of the United States of America, and having taken up arms against the said United States, it becomes a military necessity to declare them under martial law. This was accordingly done on the 25th of April, 1862. Slavery and martial law in a free country are altogether incompatible; the persons in these three States _ Georgia, Florida and South Carolina heretofore held as slaves, are therefore declared forever free.

(Official) David Hunter,

Major General Commanding

Major General Commanding

Ed H Smith,

Acting Assistant Adjutant General

And whereas the same is producing some excitement, and misunderstanding; therefore I Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, proclaim and declare, that the government of the United States, had no knowledge, information, or belief, of an intention on the part of General Hunter to issue such a proclamation; nor has it yet any authentic information that the document is genuine _ And further, that neither General Hunter, nor any other commander, or person, has been authorized by the Government of the United States, to make proclamations declaring the slaves of any State free and that the supposed proclamation, now in question, whether genuine or false, is altogether void, so far as respects such declaration.

I further make known that whether it be competent for me, as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, to declare the slaves of any State or States, free, and whether at any time, in any case, it shall have become a necessity indispensable to the maintenance of the government, to exercise such supposed power, are questions which, under my responsibility, I reserve to myself and which I cannot feel justified in leaving to the decision of commanders in the field. These are totally different questions from those of police regulations in armies and camps.

On the sixth day of March last, by a special message, I recommended to Congress the adoption of a joint resolution to be substantially as follows:

Resolved, That the United States ought to co-operate with any State which may adopt a gradual abolishment of slavery, giving to such State pecuniary aid, to be used by such State in its discretion to compensate for the inconveniences, public and private, produced by such a change of system.

The resolution, in the language above quoted, was adopted by large majorities in both branches of Congress, and now stands an authentic, definite, and solemn proposal of the nation to the States and people most immediately interested in the subject matter. To the people of those States I now earnestly appeal—I do not argue. I beseech you to make the arguments for yourselves. You can not if you would, be blind to the signs of the times. I beg of you a calm and enlarged consideration of them, ranging, if it may be far above personal and partizan politics. This proposal makes common cause for a common object, casting no reproaches upon any. It acts not the pharisee. The change it contemplates would come gently as the dews of heaven, not rending or wrecking anything. Will you not embrace it? So much good has been done, by one effort, in all past time, as in the providence of God, it is now your high privilege to do. May the vast future not have to lament that you have neglected it.

In witness thereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington

this the nineteenth day of May,

in the year of our Lord one

thousand eight hundred

and sixty two, and of the

Independence of the United

States the eighty sixth.

Abraham Lincoln

By the President

William H Seward

Secretary of State

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 4656009

Full Citation: Presidential Proclamation 90 by President Abraham Lincoln Revoking General David Hunter's Order of Military Emancipation; 5/19/1862; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/presidential-proclamation-90-president-abraham-lincoln, April 29, 2024]Activities that use this document

- From Slavery to Juneteenth: Emancipation and Ending Enslavement

Created by the National Archives Education Team

Rights: Public Domain, Free of Known Copyright Restrictions. Learn more on our privacy and legal page.