Who were some of the people who worked to end slavery?

Seeing the Big Picture

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

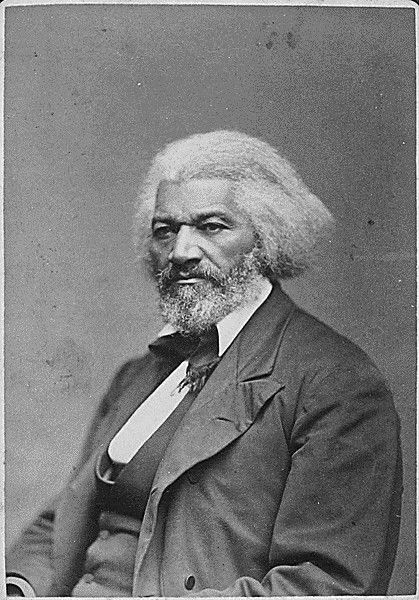

The abolitionist movement to end slavery in the United States began in the late 18th century (the 1700s). It grew and got stronger throughout the first half of the 19th century (1800s), until the Civil War erupted between the free states and the states with enslaved people.Many different people were involved in the movement to abolish slavery, and they used a variety of different strategies and methods. Look at the boxes below where you will learn about some of these people. Match each photograph of a person to the description of what they did to try to end slavery. (Click on the orange "open in new window" icons to read full descriptions and see larger pictures.)

Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

Who were some of the people who worked to end slavery?

Seeing the Big Picture

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Consider how each document or piece of text relates to each other and create matched pairs. Write the text or document number next to its match below. Write your conclusion response in the space provided.1

2

3

4

5

6

1

Activity Element

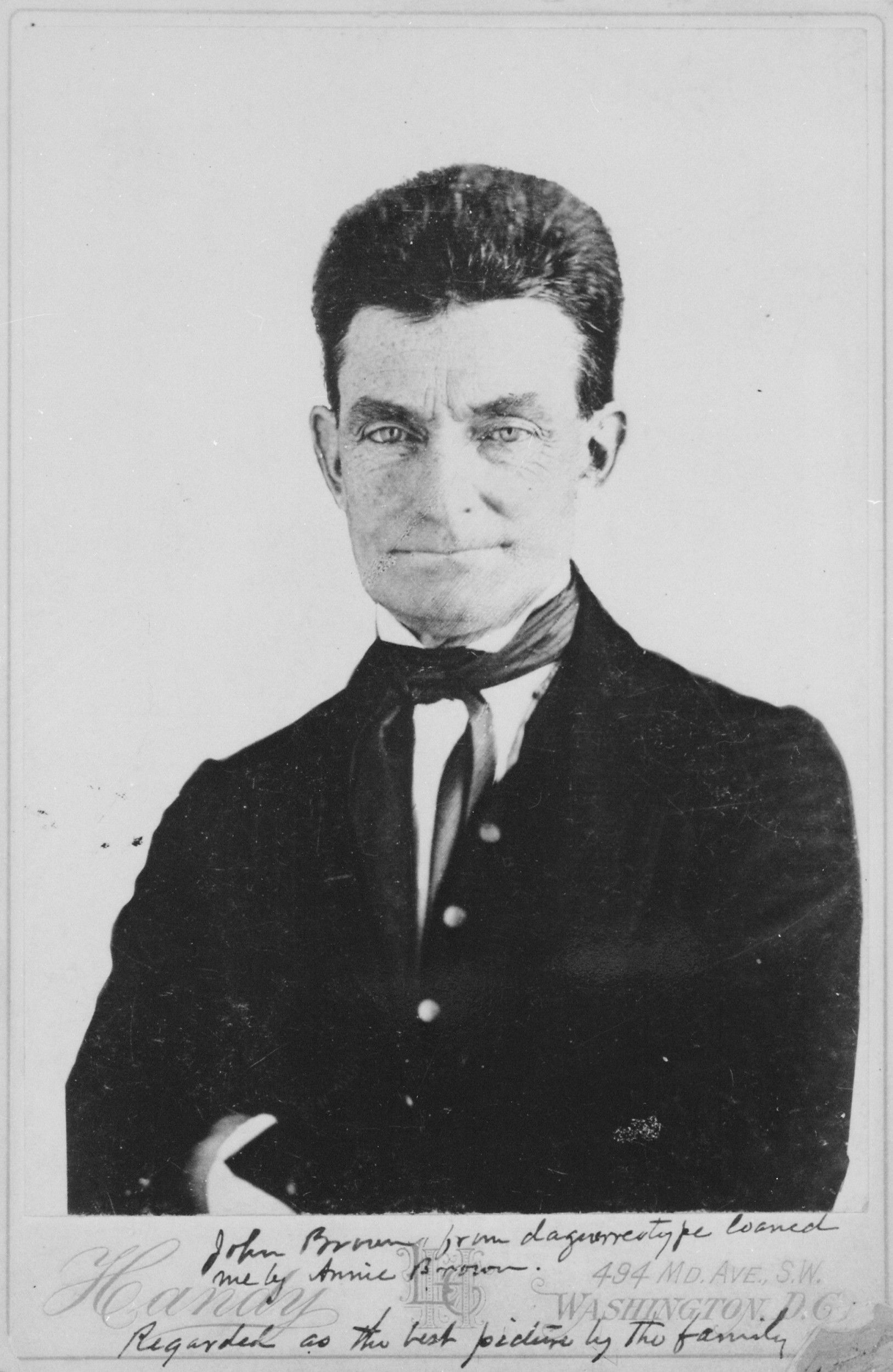

The destruction of slavery in the United States was the driving ambition of abolitionist John Brown. He believed that it would take bloodshed to root out the evil of slavery. By the mid-1850s, he dedicated himself to an all-out war for liberation. On October 16, 1859, he and his "army" of some 20 men seized the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). By the morning of October 18, Marines under the command of Bvt. Col. Robert E. Lee (who later resigned from the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy) stormed the building and captured Brown and the survivors of his party.

2

Activity Element

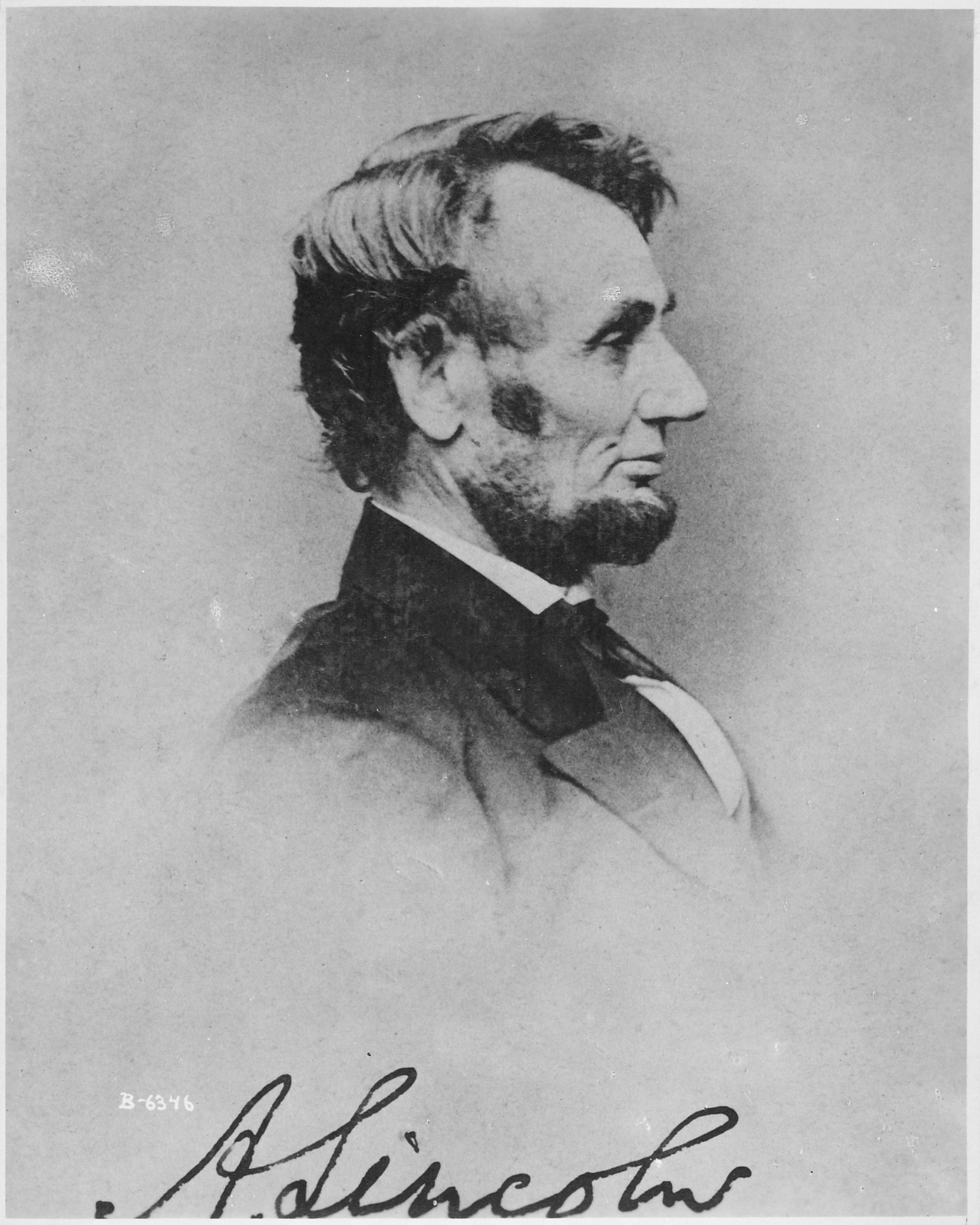

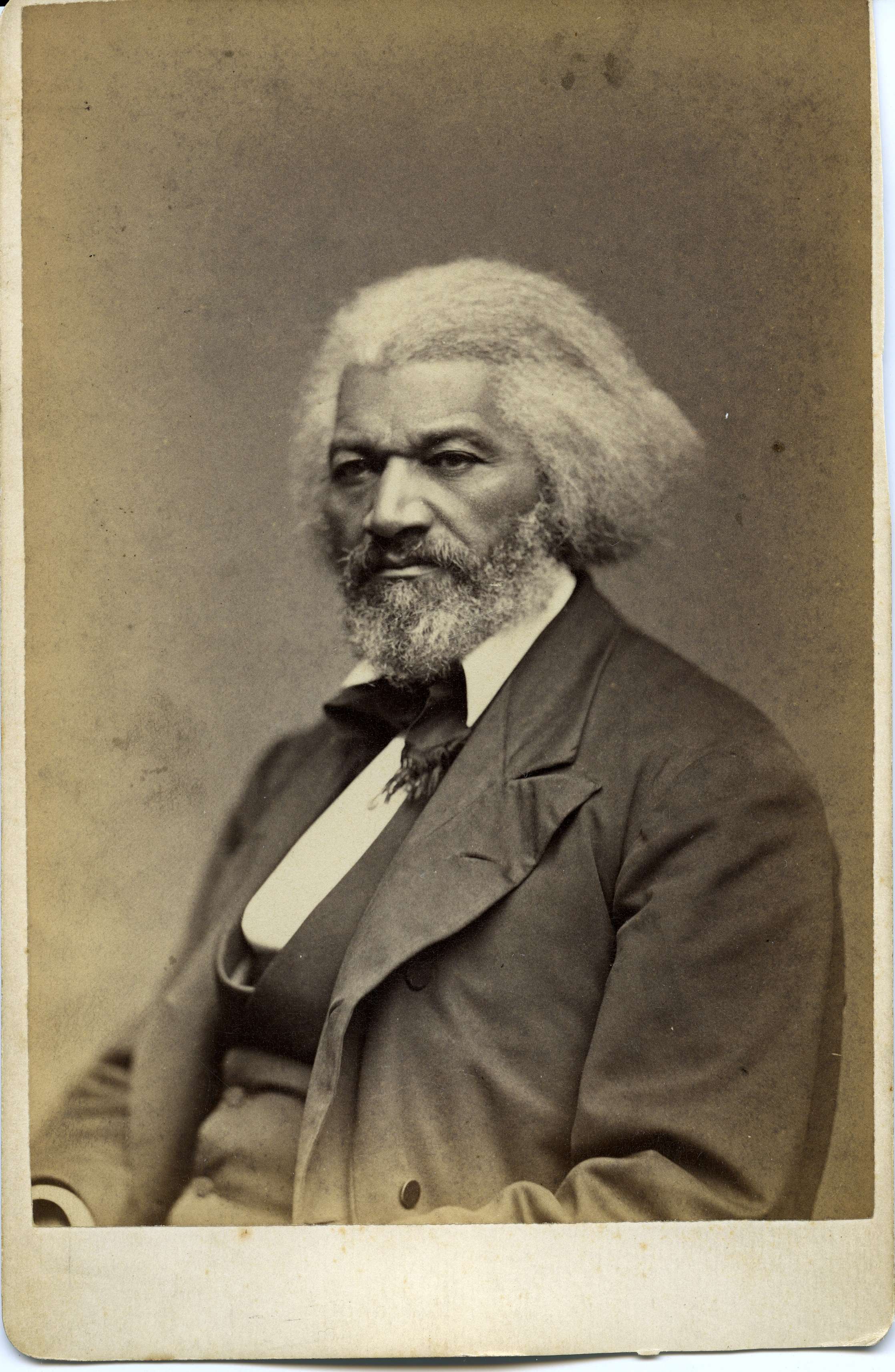

Frederick Douglass was a statesman, abolitionist, and champion of the people. He firmly believed that free men should have the right to defend their freedom, and he convinced President Lincoln of the importance of enlisting African-American troops in the Union Armies. He helped to organize the 54th Massachusetts Regiment that fought in the Civil War.

3

Activity Element

Harriet Tubman’s name is synonymous with the Underground Railroad for her work helping enslaved people escape to their freedom. Once the Civil War began and more paths to freedom opened, she concentrated her efforts on supporting the Union.

Tubman transferred the stealthy skills she mastered while working in the Underground Railroad to help the Union in the Civil War. While serving as a scout in the Union Army, Harriet Tubman earned the distinction of being the first American woman to lead American troops into battle. She also served as a nurse, cook, and spy.

Tubman transferred the stealthy skills she mastered while working in the Underground Railroad to help the Union in the Civil War. While serving as a scout in the Union Army, Harriet Tubman earned the distinction of being the first American woman to lead American troops into battle. She also served as a nurse, cook, and spy.

4

Activity Element

5

Activity Element

6

Activity Element

7

Activity Element

8

Activity Element

Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote the novel, "Uncle Tom's Cabin," to aid the cause of the abolitionism. When the novel was published in 1852, it sold an average of 10,000 copies per week. For Harriet Beecher Stowe, slavery was an abomination. In the opening of "Uncle Tom's Cabin," she wrote "So long as the law considers all these human beings, with beating hearts, and living affections...as...things belonging to a master, ...it is impossible to make anything desirable in the best regulated administration of slavery."

9

Activity Element

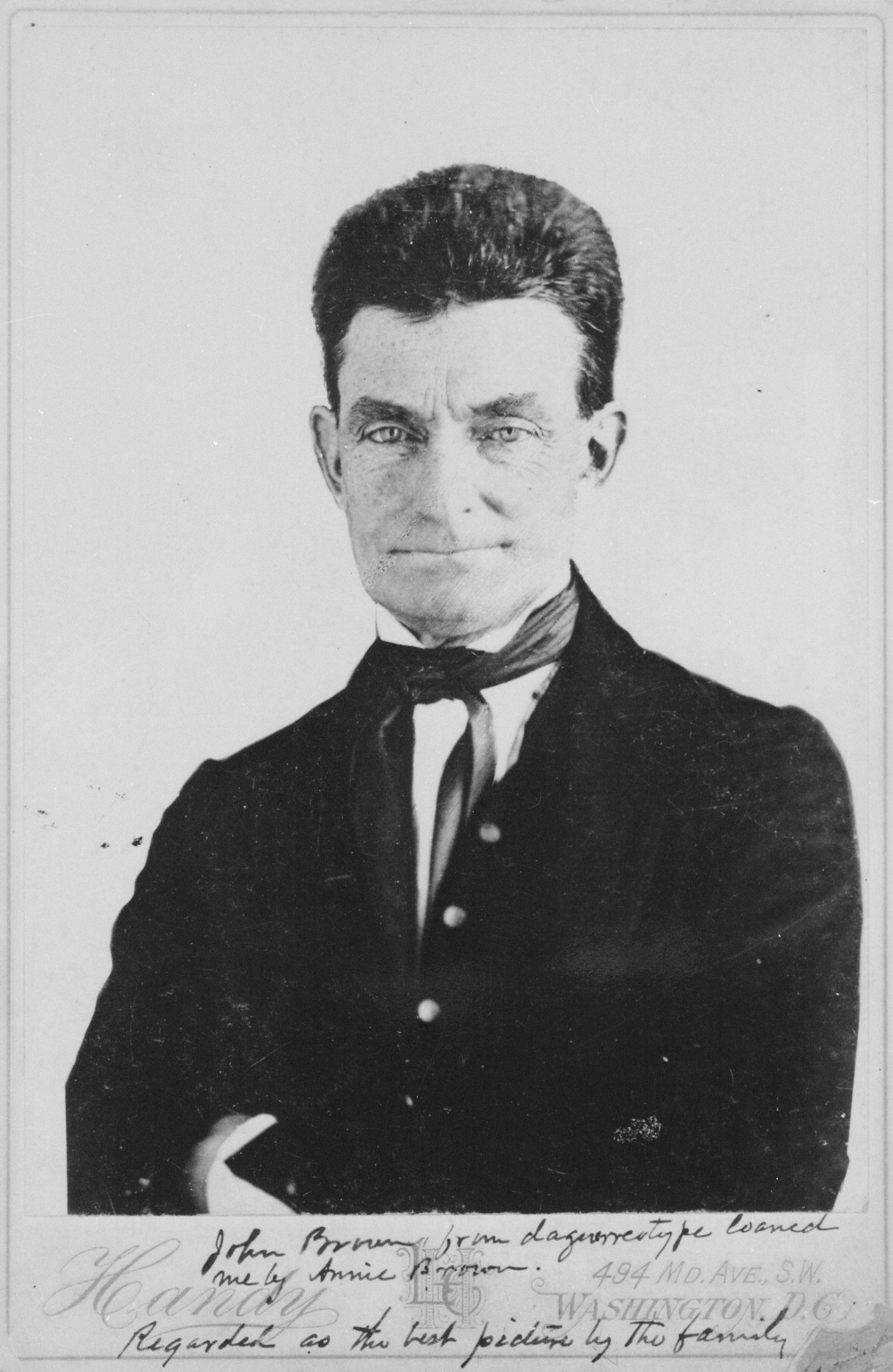

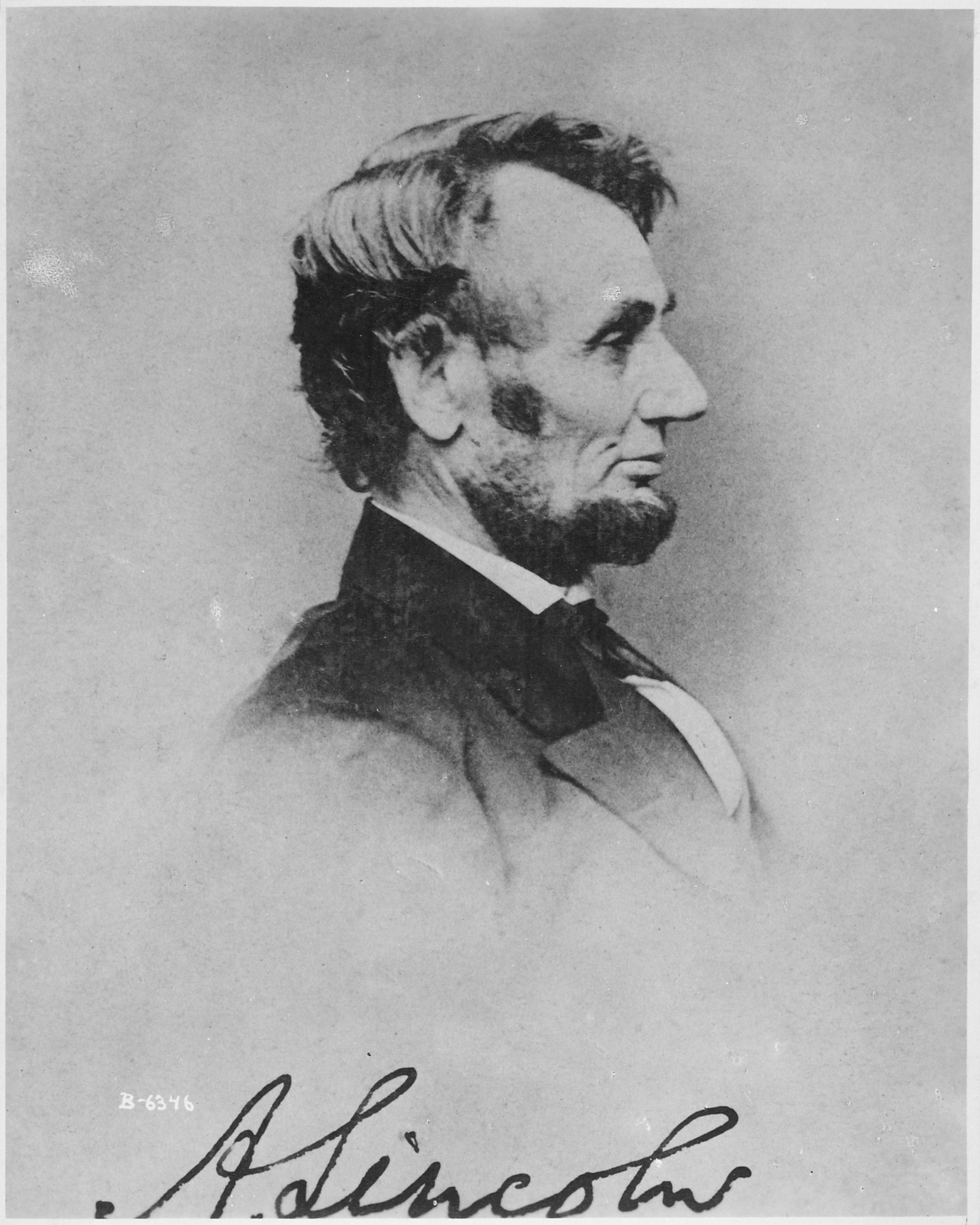

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, announcing, "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Initially, the Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that enslaved people in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free. One hundred days later, with the rebellion unabated, President issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Initially, the Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that enslaved people in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free. One hundred days later, with the rebellion unabated, President issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

10

Activity Element

11

Activity Element

12

Activity Element

William Lloyd Garrison was a journalist crusader who published the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, and helped lead the crusade against slavery. In the first issue, dated January 1, 1831, he stated his views on slavery vehemently: “I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation.… I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.”

Culminating Document

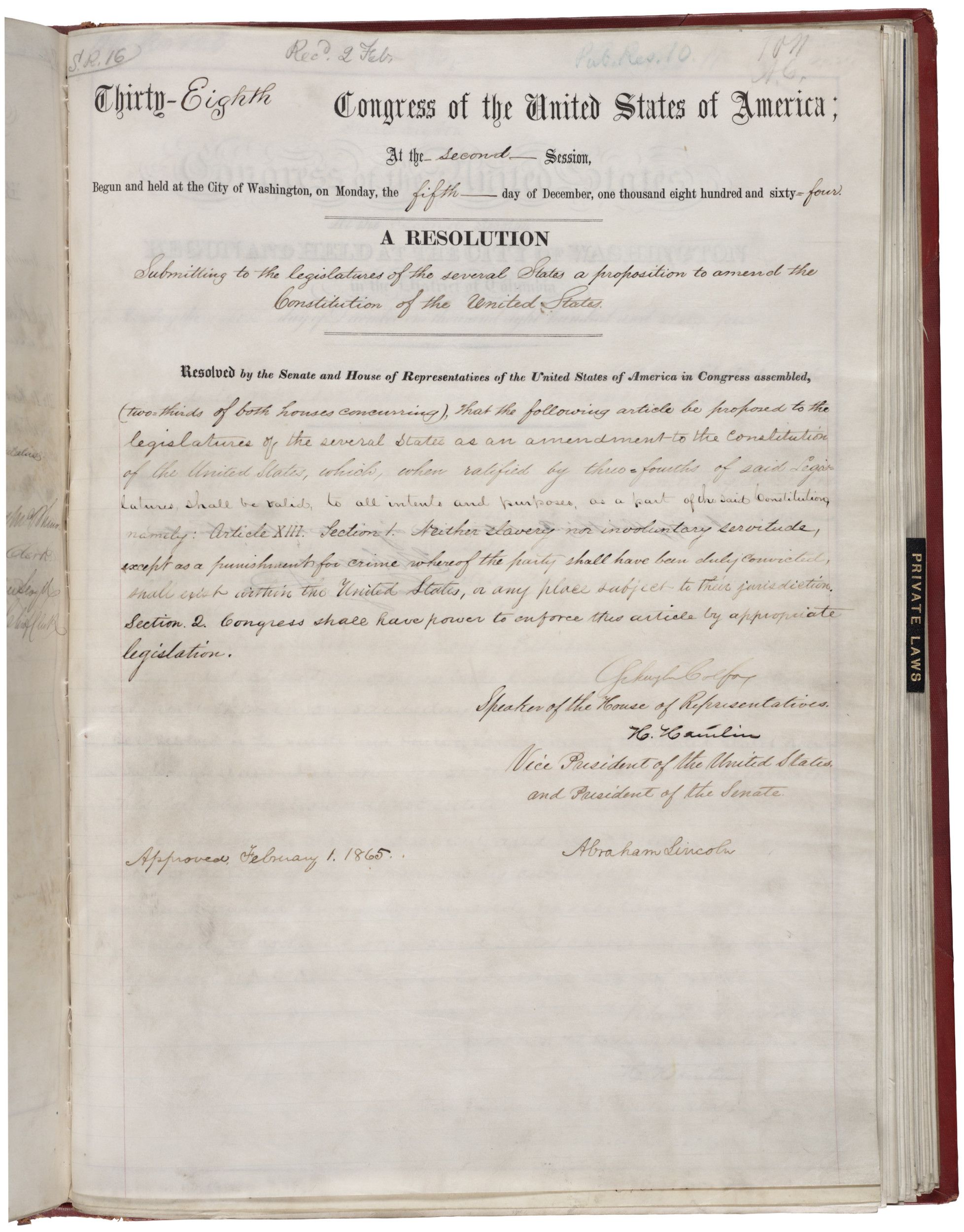

Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

1/31/1865

This is a draft of a joint resolution proposing the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution that started in the Senate. A joint resolution is a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification. This particular resolution became the 13th Amendment, ending slavery in the United States in 1865.

In 1863, President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Nonetheless, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation since it only applied to areas of the Confederacy currently in a state of rebellion (and not even to the loyal “border states” that remained in the Union). Lincoln recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

The 13th Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War before the Southern states had been restored to the Union, and should have easily passed in Congress. However, though the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through Congress. He insisted that passage of the 13th Amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming 1864 Presidential election. His efforts met with success when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119–56.

On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. The necessary number of states (three-fourths) ratified it by December 6, 1865. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery. The 13th Amendment, along with the 14th and 15th, is one of the trio of Civil War amendments that greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans.

In 1863, President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Nonetheless, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation since it only applied to areas of the Confederacy currently in a state of rebellion (and not even to the loyal “border states” that remained in the Union). Lincoln recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

The 13th Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War before the Southern states had been restored to the Union, and should have easily passed in Congress. However, though the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through Congress. He insisted that passage of the 13th Amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming 1864 Presidential election. His efforts met with success when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119–56.

On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. The necessary number of states (three-fourths) ratified it by December 6, 1865. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery. The 13th Amendment, along with the 14th and 15th, is one of the trio of Civil War amendments that greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans.

Transcript

Thirty-Eighth Congress of the United StatesAt the Second Session

Begun and held at the City of Washington, on Monday, the fifth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four

A Resolution

Submitting to the legislatures of the several States a proposition to amend the Constitution of the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

(two-thirds of both houses concurring), that the following article be proposed to the legislatures of the several states as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said Legislatures shall be

valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the said Constitution, namely: Article XIII. Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Schuyler Colfax

Speaker of the House of Representatives

Hannibal Hamlin

Vice President of the United States

and President of the Senate

Approved February 1, 1865 Abraham Lincoln

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 1408764

Full Citation: Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; 1/31/1865; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/thirteenth-amendment, April 26, 2024]Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 2

Conclusion

Who were some of the people who worked to end slavery?

Seeing the Big Picture

In 1865, the 13th amendment abolished slavery in the United States – that's the document you saw when you made all of your matches.The people you learned about who helped bring about then end of slavery were: Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, and Abraham Lincoln.

In the box below, make a list of each person and one method or strategy that they used to try to get slavery abolished.

Your Response

Document

Frederick Douglass

ca. 1879

Additional details from our exhibits and publications

Born into slavery in Maryland, Frederick Douglass became an advocate for the equality of rights for all people. If there is no struggle, there is no progress.––Frederick Douglass, August 3, 1857

This primary source comes from the Frank W. Legg Photographic Collection of Portraits of Nineteenth-Century Notables.

National Archives Identifier: 558770

Full Citation: Frederick Douglass; ca. 1879; Frank W. Legg Photographic Collection of Portraits of Nineteenth-Century Notables, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/frederick-douglass, April 26, 2024]Frederick Douglass

Page 1

Document

Great Lakes Seaway Trail - Harriet Tubman

1870s

This full-length portrait of Harriet Tubman was taken by Harvey B. Lindsley between 1871 and 1876 in Auburn, NY. Tubman stands posed, with her hands perched on a chair. She was the most famous conductor along the Underground Railroad.

Harriet Tubman’s name is synonymous with the Underground Railroad for her work helping runaway slaves escape to their freedom. Once the Civil War began and more paths to freedom opened, she concentrated her efforts on supporting the Union.

Tubman transferred the stealthy skills she mastered while working in the Underground Railroad to help the Union in the Civil War. While serving as a scout in the Union Army, Harriet Tubman earned the distinction of being the first American woman to lead American troops into battle. She also served as a nurse, cook, and spy.

After the war she received a pension as the widow of Union veteran Nelson Davis, who had served as a private in the 8th United States Colored Infantry, but she received very little compensation for her own service. For decades she petitioned Congress seeking additional benefits for her service. An increase in her pension was finally granted by an act of Congress in 1899.

Harriet Tubman’s name is synonymous with the Underground Railroad for her work helping runaway slaves escape to their freedom. Once the Civil War began and more paths to freedom opened, she concentrated her efforts on supporting the Union.

Tubman transferred the stealthy skills she mastered while working in the Underground Railroad to help the Union in the Civil War. While serving as a scout in the Union Army, Harriet Tubman earned the distinction of being the first American woman to lead American troops into battle. She also served as a nurse, cook, and spy.

After the war she received a pension as the widow of Union veteran Nelson Davis, who had served as a private in the 8th United States Colored Infantry, but she received very little compensation for her own service. For decades she petitioned Congress seeking additional benefits for her service. An increase in her pension was finally granted by an act of Congress in 1899.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Federal Highway Administration.

National Archives Identifier: 7718799

Full Citation: Photograph 406-NSB-052-395px-Harriet_Tubman.jpg; Great Lakes Seaway Trail - Harriet Tubman; 1870s; Digital Photographs Relating to America's Byways, ca. 1995 - ca. 2013; Records of the Federal Highway Administration, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/harriet-tubman-photograph, April 26, 2024]Great Lakes Seaway Trail - Harriet Tubman

Page 1

Document

Harriet Beecher Stowe, circa 1870s-80s

ca. 1870s - 1880s

Harriet Beecher Stowe, seen in this image from the 1870s-80s, was an abolitionist, author, and figure in the woman suffrage movement. She wrote more than 20 books and was influential both for her writing and her public stance on social issues of the day.

Her most known work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), was a depiction of life for enslaved people in the mid-19th century. It energized antislavery forces in the North and provoked widespread anger in the South.

After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which punished anyone who offered food or temporary shelter to enslaved people who ran away, and following the loss of her 18-month-old son, Samuel, Stowe was inspired to write about slavery. She used the personal accounts of formerly enslaved people to write her antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life Among the Lowly. When it first appeared in installments in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era between June 5, 1851 and April 1, 1852, it met with hostility by slavery proponents.

Stowe expected that she would write the story in three or four installments, but she eventually wrote more than 40. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was then published as a two-volume book in 1852. It was a best seller in the United States, Britain, and Europe and was translated into over 60 languages.

The book received both high praise and harsh criticism and propelled Stowe and the issue of slavery into the international spotlight. Slavery proponents argued that the novel was nothing more than abolitionist propaganda. In the South, and in the North too, people protested that the depiction of slavery had been melodramatically twisted. Southerners particularly promoted the idea that the institution of slavery was benevolent and benign. Responding to charges that the book was a distortion, Stowe published another book, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which documented the actual cases upon which her book was based to refute critics’ claims that her work was fabricated and based on supposition.

Later, Stowe embraced woman suffrage and briefly considered an alliance with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who tried in 1869 to recruit her to write for their newspaper, The Revolution. Stowe declined the partnership, but eventually developed a deeper empathy for the women’s rights movement and the activities of the suffragists. She wrote a series for the Atlantic, and in one installment, she wrote, “The question of Woman and her Sphere is now, perhaps, the greatest of the age....If the principles on which we founded our government are true, that taxation must not exist without representation, and if women hold property and are taxed, it follows that women should be represented in the State by their votes, or there is an illogical working of our government.”

Throughout her life, Stowe used literature to shape public opinion and leaned on her own experiences as a woman and a mother. She was keenly aware of racial differences and regional customs, and it translated into her distinct influence on the American experience. Writing at a time when women were denied the vote and had no representation in Congress, Stowe used literature as her political voice.

Her most known work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), was a depiction of life for enslaved people in the mid-19th century. It energized antislavery forces in the North and provoked widespread anger in the South.

After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which punished anyone who offered food or temporary shelter to enslaved people who ran away, and following the loss of her 18-month-old son, Samuel, Stowe was inspired to write about slavery. She used the personal accounts of formerly enslaved people to write her antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life Among the Lowly. When it first appeared in installments in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era between June 5, 1851 and April 1, 1852, it met with hostility by slavery proponents.

Stowe expected that she would write the story in three or four installments, but she eventually wrote more than 40. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was then published as a two-volume book in 1852. It was a best seller in the United States, Britain, and Europe and was translated into over 60 languages.

The book received both high praise and harsh criticism and propelled Stowe and the issue of slavery into the international spotlight. Slavery proponents argued that the novel was nothing more than abolitionist propaganda. In the South, and in the North too, people protested that the depiction of slavery had been melodramatically twisted. Southerners particularly promoted the idea that the institution of slavery was benevolent and benign. Responding to charges that the book was a distortion, Stowe published another book, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which documented the actual cases upon which her book was based to refute critics’ claims that her work was fabricated and based on supposition.

Later, Stowe embraced woman suffrage and briefly considered an alliance with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who tried in 1869 to recruit her to write for their newspaper, The Revolution. Stowe declined the partnership, but eventually developed a deeper empathy for the women’s rights movement and the activities of the suffragists. She wrote a series for the Atlantic, and in one installment, she wrote, “The question of Woman and her Sphere is now, perhaps, the greatest of the age....If the principles on which we founded our government are true, that taxation must not exist without representation, and if women hold property and are taxed, it follows that women should be represented in the State by their votes, or there is an illogical working of our government.”

Throughout her life, Stowe used literature to shape public opinion and leaned on her own experiences as a woman and a mother. She was keenly aware of racial differences and regional customs, and it translated into her distinct influence on the American experience. Writing at a time when women were denied the vote and had no representation in Congress, Stowe used literature as her political voice.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of War Information.

National Archives Identifier: 535784

Full Citation: Photograph 208-N-25004; Harriet Beecher Stowe, circa 1870s-80s; ca. 1870s - 1880s; Photographs of Allied and Axis Personalities and Activities, 1942 - 1945; Records of the Office of War Information, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/harriet-beecher-stowe, April 26, 2024]Harriet Beecher Stowe, circa 1870s-80s

Page 1

Document

Garrison, William Lloyd; three-quarter-length, seated

ca. 1860 - 1865

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives Identifier: 530489

Full Citation: Garrison, William Lloyd; three-quarter-length, seated; ca. 1860 - 1865; Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/garrison-william-lloyd-threequarterlength-seated, April 26, 2024]Garrison, William Lloyd; three-quarter-length, seated

Page 1

Document

Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln

ca. 1860-1865

Shortly after being elected the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln faced a divided nation. The Civil War lasted almost his entire Presidency. Just weeks into his second term as President, Lincoln was assassinated while watching a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives Identifier: 530413

Full Citation: Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln; ca. 1860-1865 ; Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, 1921 - 1940; Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/photograph-of-president-abraham-lincoln, April 26, 2024]Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln

Page 1

Document

Abolitionist John Brown

ca. 1850

Abolitionist John Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut, to a deeply religious Congregationalist and overtly antislavery family. At age five, his family moved west to Hudson, Ohio, where his father, Owen Brown, owned a successful tannery and supported the founding of Oberlin College, a racially inclusive co-ed high learning institution with an antislavery curriculum.

In 1825 Brown moved to western Pennsylvania. He opened his own tannery and started the Franklin Land Company with 700 acres for suburban development. The tannery was a major stop on the underground railroad. However, the panic of 1837, a financial crisis that caused plunging profits, prices, and wages and increasing unemployment, bankrupted Brown.

After the crisis, Brown emerged as an unyielding abolitionist. In 1851 he helped found the League of Gileadites, an organization of whites, free blacks, and runaway slaves dedicated to protecting fugitive slaves from slave catchers. By the end of 1856, Brown was one of the most renowned figures in “bleeding Kansas,” the violent confrontations over the legality of slavery in the Kansas territory.

On Sunday, October 16, 1859, Brown and his men began their raid on Harpers Ferry. Brown considered Harpers Ferry an ideal location to attack because it was close to a relatively high population of slaves; its proximity to the Blue Ridge mountain range offered an escape route; and the Federal armory and arsenal contained weapons Brown could use to defend himself.

After completing their mission, instead of running for the hills, Brown and his men remained in the armory in Harpers Ferry awaiting the army of slaves that Brown thought would rise up to join them. They never came. Brown was in custody before midday on October 18. Brown’s trial and sentence were carried out swiftly, and on December 2, 1859, he was hanged for treason, murder, and conspiring with slaves to rebel.

In 1825 Brown moved to western Pennsylvania. He opened his own tannery and started the Franklin Land Company with 700 acres for suburban development. The tannery was a major stop on the underground railroad. However, the panic of 1837, a financial crisis that caused plunging profits, prices, and wages and increasing unemployment, bankrupted Brown.

After the crisis, Brown emerged as an unyielding abolitionist. In 1851 he helped found the League of Gileadites, an organization of whites, free blacks, and runaway slaves dedicated to protecting fugitive slaves from slave catchers. By the end of 1856, Brown was one of the most renowned figures in “bleeding Kansas,” the violent confrontations over the legality of slavery in the Kansas territory.

On Sunday, October 16, 1859, Brown and his men began their raid on Harpers Ferry. Brown considered Harpers Ferry an ideal location to attack because it was close to a relatively high population of slaves; its proximity to the Blue Ridge mountain range offered an escape route; and the Federal armory and arsenal contained weapons Brown could use to defend himself.

After completing their mission, instead of running for the hills, Brown and his men remained in the armory in Harpers Ferry awaiting the army of slaves that Brown thought would rise up to join them. They never came. Brown was in custody before midday on October 18. Brown’s trial and sentence were carried out swiftly, and on December 2, 1859, he was hanged for treason, murder, and conspiring with slaves to rebel.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Marine Corps.

National Archives Identifier: 532587

Full Citation: Abolitionist John Brown ; ca. 1850; Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/abolitionist-john-brown, April 26, 2024]Abolitionist John Brown

Page 1