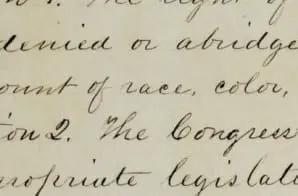

Passed by Congress on February 26, 1869, and ratified February 3, 1870, the 15th amendment granted African-American men the right to vote: the right of male U.S. citizens to vote shall not be denied or abridged “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This document is the joint resolution – a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch – proposing the amendment. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the 15th amendment appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the 13th amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the 14th amendment, Black males were given the vote by the 15th amendment.

African Americans voted and held office in many Southern states through the 1880s, but in the early 1890s, steps were taken to ensure subsequent “white supremacy.” The 15th Amendment had been carefully worded to maximize its chances of ratification. It didn’t go so far as to grant the right to vote to all citizens regardless of race —instead, it barred states from denying suffrage based on race, opening a loophole for literacy, land ownership, or other requirements. It was a loophole that Southern states quickly exploited to effectively ban Black people from the polls.

Literacy tests for the vote, “grandfather clauses” excluding those whose ancestors had not voted in the 1860s, and other devices to disenfranchise African Americans were written into the laws of former Confederate states.

Social and economic segregation were added to Black America’s loss of political power. In 1896, the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson legalized “separate but equal” facilities for the races. For more than 50 years, the overwhelming majority of African American citizens were reduced to second-class citizenship under the “Jim Crow” segregation system.

During that time, African Americans sought to secure their rights and improve their position through organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) and the National Urban League, and through the individual efforts of reformers like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and A. Philip Randolph.

The most direct attack on the problem of African-American disfranchisement came in 1965. Prompted by reports of continuing discriminatory voting practices in many Southern states, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Congress to pass legislation “which will make it impossible to thwart the 15th amendment.” He reminded Congress that “we cannot have government for all the people until we first make certain it is government of and by all the people.”

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, extended in 1970, 1975, and 1982, abolished all remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorized federal supervision of voter registration where necessary. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the act involving federal oversight of voting rules in nine states.

The 15th Amendment is a part of America’s 100 Docs, an initiative of the National Archives Foundation in partnership with More Perfect that invites the American public to vote on 100 notable documents from the holdings of the National Archives. Visit 100docs.vote today.