Dunlap Broadside

Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

A National Archives Foundation educational resource using primary sources from the National Archives

Published By:

Historical Era:

Thinking Skill:

Bloom’s Taxonomy:

Grade Level:

This activity can be used during a unit on the American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, or while exploring key American ideals and values from our Founding documents. For grades 9-12. Approximate time needed is 45-60 minutes. Students can complete the activity individually, in pairs, or in small groups.

Begin the activity by asking students what they already know about the American Revolution in general and the Declaration of Independence specifically. Ask students to take 60 seconds to brainstorm people, places, events, and concepts they associate with these terms in small groups or pairs.

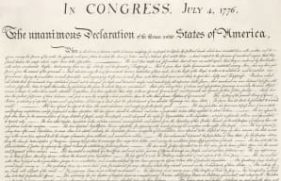

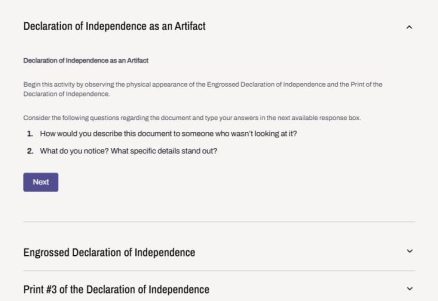

After discussing their ideas as a class, introduce the activity. Inform students that they will be doing a close reading of the Declaration of Independence. But first they will be looking at the Engrossed Declaration of Independence and a Print of the Declaration of Independence as an object/artifact. Tell students to focus on the following questions and answer in the next available blank response box:

After discussing their observations, direct students to the Dunlap Broadside copy of the Declaration of Independence. Inform students they will be analyzing this printed version of the Declaration of Independence as a primary source by specifically answering the following in the next available blank response box:

After analyzing it as a primary source, tell students they are now going to analyze the language of the Declaration of Independence as a persuasive argument. They will be looking at short sections of the document. This portion of the activity can be completed individually, in pairs, or in small groups and/or as a jigsaw activity where different students explore an individual section of the document. Direct students to answer the following questions in the next available blank response box:

After reading the selections, ask students to enter their answer in the blank text box that follows, or to conduct a turn-and-talk with a partner to share their phrase and word selections and explain why they were chosen. Ask students to volunteer their phrase and word selections, with explanations, for the rest of the class. As students share, ask if other students selected the same phrase or word, and facilitate a conversation about the reasons why specific phrases and words were selected. After discussing their word choices, ask students to evaluate the argument for independence–is this a strong or weak argument for independence?

After completing the activity, students should click on “When You’re Done” and answer the following:

Share the following historical context, if necessary:

In the early 1770s, more and more colonists became convinced that Parliament intended to take away their freedom. In fact, the Americans saw a pattern of increasing oppression and corruption happening all around the world. Parliament was determined to bring its unruly American subjects to heel. Britain began to prepare for war in early 1775. The first fighting broke out in April in Massachusetts. In August, the King declared the colonists “in a state of open and avowed rebellion.” For the first time, many colonists began to seriously consider cutting ties with Britain. The publication of Thomas Paine’s stirring pamphlet Common Sense in early 1776 lit a fire under this previously unthinkable idea. The movement for independence was now in full swing.

The colonists elected delegates to attend a Continental Congress that eventually became the governing body of the union during the Revolution. Its second meeting convened in Philadelphia in 1775. The delegates to Congress adopted strict rules of secrecy to protect the cause of American liberty and their own lives. In less than a year, most of the delegates abandoned hope of reconciliation with Britain. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution “that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states.” They appointed a Committee of Five to write an announcement explaining the reasons for independence. Thomas Jefferson, who chaired the committee and had established himself as a bold and talented political writer, wrote the first draft.

On June 11, 1776, Jefferson holed up in his Philadelphia boarding house and began to write. He borrowed freely from existing documents like the Virginia Declaration of Rights and incorporated accepted ideals of the Enlightenment. Jefferson later explained that “he was not striving for originality of principal or sentiment.” Instead, he hoped his words served as an “expression of the American mind.” Less than three weeks after he’d begun, he presented his draft to Congress. He was not pleased when Congress “mangled” his composition by cutting and changing much of his carefully chosen wording. He was especially sorry they removed the part blaming King George III for the slave trade, although he knew the time wasn’t right to deal with the issue.

On July 2, 1776, Congress voted to declare independence. Two days later, it ratified the text of the Declaration. John Dunlap, official printer to Congress, worked through the night to set the Declaration in type and print approximately 200 copies. These copies, known as the Dunlap Broadsides, were sent to various committees, assemblies, and commanders of the Continental troops. The Dunlap Broadsides weren’t signed, but John Hancock’s name appears in large type at the bottom. One copy crossed the Atlantic, reaching King George III months later. The official British response scolded the “misguided Americans” and “their extravagant and inadmissable Claim of Independency.”

For additional materials related to Declaration of Independence Close Reading (including Guiding Questions, National Standards, Historical Background and Supplemental Educational Resources).

In this activity, students will explore the Declaration of Independence through a close reading. They will explore three different versions of the Declaration of Independence (the Engrossed copy, a Print, and the Dunlap Broadside) as an object, a primary source, and a persuasive argument.