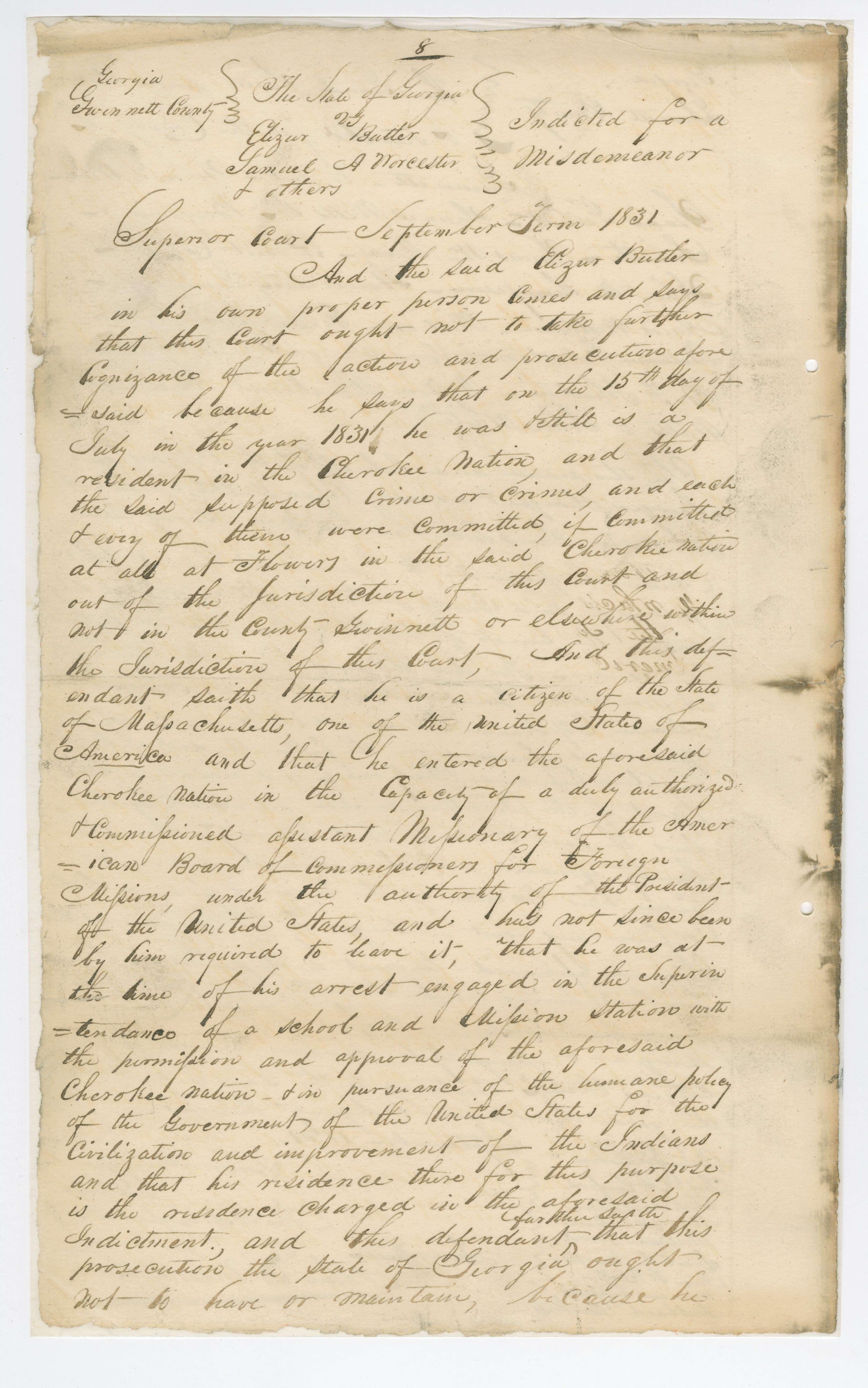

Butler and Worcester's Testimony in Response to Their Indictment

9/15/1831

Add to Favorites:

Add all page(s) of this document to activity:

Add only page 1 to activity:

Add only page 2 to activity:

Add only page 3 to activity:

Add only page 4 to activity:

In 1830, Georgia passed a law requiring non-Cherokee to obtain a permit from the state of Georgia to reside on Cherokee land. A group of missionaries, including Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler, were indicted after they went to live on Cherokee land in Georgia with permission from the Cherokee Nation and the U.S. Government.

Worcester and Butler pleaded not guilty. This document provides an account of Butler's explanation, and Worcester's sworn agreement, in a Georgia court as to why the State of Georgia should not have charged them. He argues that Georgia lacked jurisdiction to try and punish them. The document comes from the case file for Worcester v. Georgia.

The Georgia court found them guilty, and sentenced them to four years of hard labor. They appealed. After they were unsuccessful in the highest state court, they appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court on a writ of error (which demands the lower court provide the full record to a higher court for review of errors) in Worcester v. Georgia. The Federal question raised (necessary to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court) was whether the state of Georgia had jurisdiction, since the men were present in the territory under authority of the U.S. President doing missionary work, and with the permission of the Cherokee Nation. In other words, did the state of Georgia have the authority to hear the case or to pass laws concerning sovereign Indian nations?

The question had been asked of the Supreme Court before. In 1828, Georgia had passed a series of acts taking away rights of Cherokees residing within the state, including Cherokee removal from land that the state wanted. The Cherokee asserted that Georgia did not have the jurisdiction or authority to do these things, since the Cherokee Nation was sovereign and protected under a treaty with the United States. They sought an injunction — or order to stop what the State of Georgia was doing — from the U.S. Supreme Court in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia in 1831. The Supreme Court said they lacked jurisdiction to hear the case and it was dismissed, leaving the Cherokee at the mercy of the laws of the state of Georgia.

In Worcester v. Georgia in 1832, however, the Supreme Court ruled that states, like Georgia, could not diminish rights of tribes because the Cherokee Nation constituted a nation holding distinct sovereign powers as granted by Congress and the United States. This established the principle of "tribal sovereignty." The Court also issued a mandate to release Worcester and Butler.

Georgia ignored the ruling, however, and did not release the men. President Andrew Jackson did not intervene to enforce the Supreme Court ruling. (Georgia Governor Wilson Lumpkin pardoned Butler and Worcester in 1833.)

So the judicial branch handed down a ruling that should have freed Butler and Worcester and established more sovereignty for the tribes; but it didn't have that effect because the executive branch did not enforce it.

President Andrew Jackson had called for the relocation of eastern Native American tribes to land west of the Mississippi River, and Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act, in 1830. The Cherokee were forcibly removed from Georgia — a journey west that became known as the “Trail of Tears” because of the thousands of deaths along the way.

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2016 summer workshop in Washington, D.C.

Worcester and Butler pleaded not guilty. This document provides an account of Butler's explanation, and Worcester's sworn agreement, in a Georgia court as to why the State of Georgia should not have charged them. He argues that Georgia lacked jurisdiction to try and punish them. The document comes from the case file for Worcester v. Georgia.

The Georgia court found them guilty, and sentenced them to four years of hard labor. They appealed. After they were unsuccessful in the highest state court, they appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court on a writ of error (which demands the lower court provide the full record to a higher court for review of errors) in Worcester v. Georgia. The Federal question raised (necessary to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court) was whether the state of Georgia had jurisdiction, since the men were present in the territory under authority of the U.S. President doing missionary work, and with the permission of the Cherokee Nation. In other words, did the state of Georgia have the authority to hear the case or to pass laws concerning sovereign Indian nations?

The question had been asked of the Supreme Court before. In 1828, Georgia had passed a series of acts taking away rights of Cherokees residing within the state, including Cherokee removal from land that the state wanted. The Cherokee asserted that Georgia did not have the jurisdiction or authority to do these things, since the Cherokee Nation was sovereign and protected under a treaty with the United States. They sought an injunction — or order to stop what the State of Georgia was doing — from the U.S. Supreme Court in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia in 1831. The Supreme Court said they lacked jurisdiction to hear the case and it was dismissed, leaving the Cherokee at the mercy of the laws of the state of Georgia.

In Worcester v. Georgia in 1832, however, the Supreme Court ruled that states, like Georgia, could not diminish rights of tribes because the Cherokee Nation constituted a nation holding distinct sovereign powers as granted by Congress and the United States. This established the principle of "tribal sovereignty." The Court also issued a mandate to release Worcester and Butler.

Georgia ignored the ruling, however, and did not release the men. President Andrew Jackson did not intervene to enforce the Supreme Court ruling. (Georgia Governor Wilson Lumpkin pardoned Butler and Worcester in 1833.)

So the judicial branch handed down a ruling that should have freed Butler and Worcester and established more sovereignty for the tribes; but it didn't have that effect because the executive branch did not enforce it.

President Andrew Jackson had called for the relocation of eastern Native American tribes to land west of the Mississippi River, and Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act, in 1830. The Cherokee were forcibly removed from Georgia — a journey west that became known as the “Trail of Tears” because of the thousands of deaths along the way.

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2016 summer workshop in Washington, D.C.

Transcript

8Georgia

Gwinnett County

The State of Georgia vs

Elizur Butler, Samuel A Worcester & others

Indicted for a Misdemeanor

Superior Court — September Term 1831

And the said Elizur Butler in his own proper person comes and says that this court ought not to take further of this cognizance action and prosecutions aforesaid because he says that on the 15th day of July in the year 1831 he was & still is a resident in the Cherokee Nation, and that the said supposed crime or crimes and each & every of them were committed, if committed at all at Flowers in the said Cherokee Nation out of the Jurisdiction of this Court and not in the County Gwinnett or elsewhere within the Jurisdiction of this Court, And this defendant saith that he is a citizen of the State of Massachusetts, one of the United States of America and that he entered the aforesaid Cherokee Nation in the capacity of a duly authorized & commissioned assistant Missionary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, under the authority of the President of the United States, and has not since been by him required to leave it, that he was at the time of his arrest engaged in the Superintendence of a school and Mission station with the permission and approval of the aforesaid Cherokee Nation & in pursuance of the humane policy of the Government of the United States for that civilization and improvement of the Indians and that his residence there for this purpose is the residence charged in the aforesaid Indictment, and this defendant ^further saith that this prosecution the State of Georgia ought not to have or maintain, because he

9

saith that several Treaties have from time to time been entered into between the United States and the Cherokee Nation of Indians (to wit) at Hopewell on the 28th day of Nov. 1785 at Holeston the 2nd day of July 1791 at Philadelphia on the 25th day of June 1794 at Tellico on the 2nd day of Oct. 1798, at Tellico on the 24th day of Oct 1804, at Tellico on the 25th day of Oct 1805 at Tellico on the 27th day of Oct 1805, at Washington City on the 7th day January 1806 at Washington City on the 22nd day of March 1816 at the Chickasaw Council House on the 14th day of September 1816, at the Cherokee Agency on the 8th day of July 1817 and at Washington City on the 29th day of Feby 1819. All which treaties have been Duly ratified by the Senate of the United States of America and by which Treaties the United States acknowledges the said Cherokee Nation to be a sovereign nation, authorized to govern themselves and all persons who have settled within their territory free from any right of Legislative interference by the several states composing the United States of America, in reference to acts done within their own Territory, and by which treaties the whole of the Territory now occupied by the Cherokee Nation on the east of the Mississippi has been solemnly guaranteed to them, all of which treaties are existing treaties at this day & in full force, by these treaties and particularly by the treaties of Hopewell & Holeston the aforesaid Territory is acknowledged to be without the Jurisdiction of the Several States composing the Union of the United States, And it is thereby specially

10

stipulated that the Citizens of the United States shall not enter the aforesaid Territory, even on a visit without a passport from the Governor of a State or from some one duly authorized thereto, by the President of the United States all of which will more fully and at large appear by reference to the aforesaid Treaties, And this defendant saith that the Several acts charged in the Bill of Indictment were done or omitted to be done if at all, within the said Territory so recognized as belonging to the said Nation and so as aforesaid held by them under the guaranty of the United States that for those acts the defendant is not amenable to the laws of Georgia nor to the Jurisdiction of the Courts of the said State, and that the Laws of the State of Georgia which profess to add the said Territory to the several adjacent counties of the said State and to extend the laws of Georgia, over the said Territory and persons inhabiting the same and in particular the act on which the Indictment against this defendant is grounded, (To wit “An act to prevent the exercise of assumed an arbitrary power by all persons under [illegible] of authority from the Cherokee Indians and their Laws, and to prevent white persons from residing within that part of the Chartered limits of Georgia occupied by the Cherokee Indians, and to provide a guard for the protection of the Gold mines & to enforce the laws of the State within the aforesaid Territory are

11

void & of no effect – That the said laws of Georgia are also unconstitutional & void, because they impair the obligation of the various contracts, formed by and between the aforesaid Cherokee Nation, and the said United States of America as above incited, Also that the said Laws of Georgia are unconstitutional and void because they impare the obligation of the various contracts, formed by and between the aforesaid Cherokee Nation, and the said United States of America as above cited, also that the said Laws of Georgia are unconstitutional and void because they interfere with & attempt to regulate & control the intercourse with the said Cherokee Nation – which by the said Constitution belongs exclusively to the Congress of the United States & Because the said Laws are repugnant to the Statute of the United States passed on the – day of March 1802 entitled an Act to regulate Trade & further intercourse with the Indian tribes & to preserve peace on the frontiers, and that therefore this Court has no Jurisdiction to cause this defendant to make further or other answer to the said Bill of Indictment or further to try & punish this defendant for the said supposed offense or offences alleged in the Bill of Indictment, or any of them & therefore this defendant prays Judgment written he shall be held bound to answer further to said Indictment

Georgia Gwinnett County Personally appeared in open court Samuel A. Worcester and being sworn saith that the several matters and things contained in the above and foregoing plea are true in substance & in fact.

S. A. Worcester

Sworn to & Subscribed in open court this 15th Sept 1831

John G. Park Clk

This primary source comes from the Records of the Supreme Court.

National Archives Identifier: 38995510

Full Citation: Butler and Worcester's Testimony in Response to Their Indictment; 9/15/1831; Appellate Case File Number 1705; Case File for Worcester v. Georgia; Appellate Jurisdiction Case Files, 1792-2010; Records of the Supreme Court, Record Group 267; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/worcester-v-georgia-response-to-indictment, April 19, 2024]Rights: Public Domain, Free of Known Copyright Restrictions. Learn more on our privacy and legal page.