Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al.

1960

Add to Favorites:

Add all page(s) of this document to activity:

Add only page 1 to activity:

Add only page 2 to activity:

Add only page 3 to activity:

Add only page 4 to activity:

Add only page 5 to activity:

Add only page 6 to activity:

Add only page 7 to activity:

In 1957, Frank Kameny was fired from his job in the Army Map Service as an astronomer because of his sexual orientation. He had been arrested in California a year earlier for consensual contact with another man. This happened during a time known as the Lavender Scare. Beginning in the late 1940s and continuing through the 1960s, thousands of gay employees were fired or forced to resign from the federal workforce because of their sexuality. This wave of repression was also bound up with anti-Communism and fueled by the power of congressional investigation.

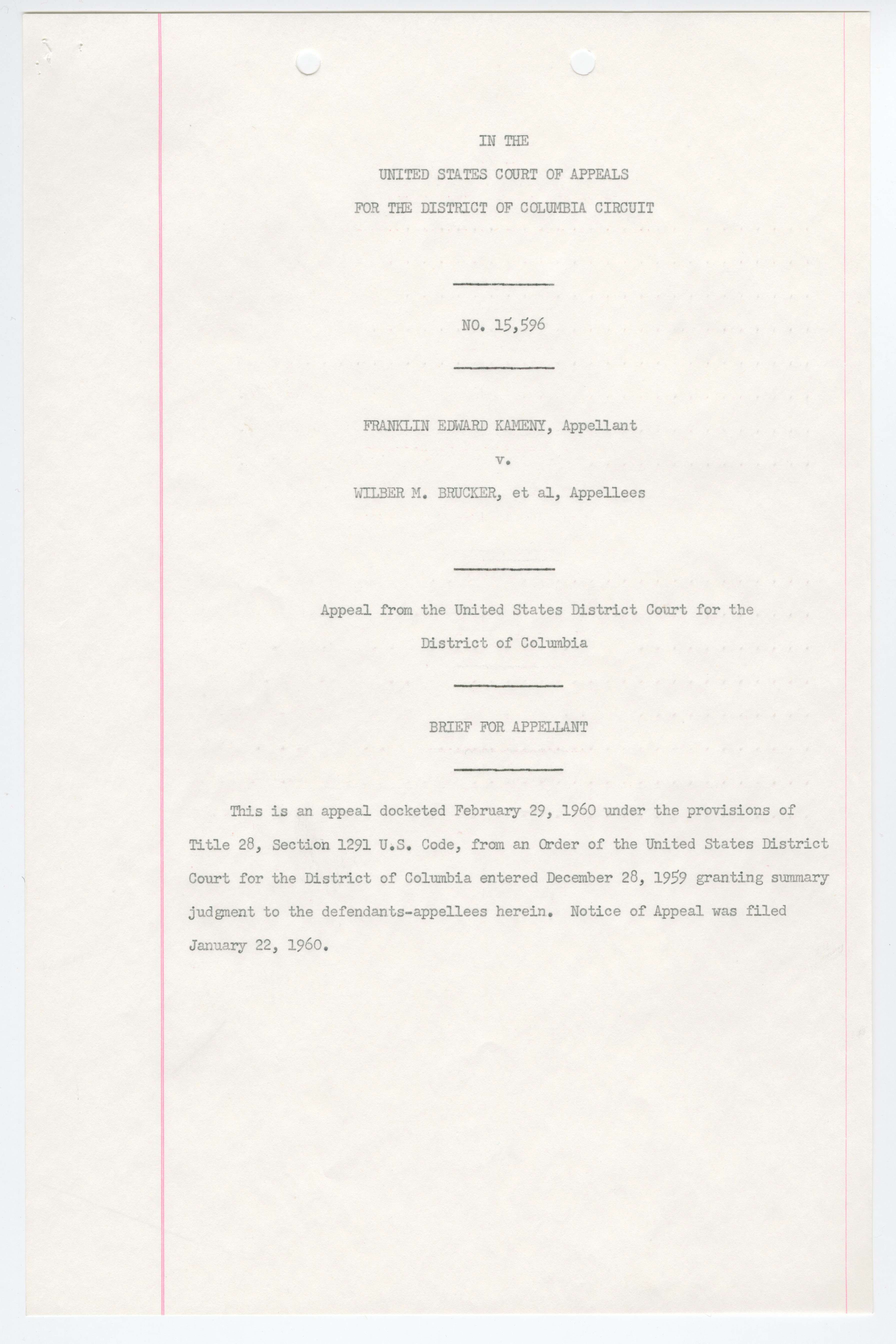

Kameny sought to have the termination of his employment overturned by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. That court did not rule in his favor. The documents shown here are his appeal of that lower court decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Ulitmately, Kameny appealed his firing all the way to the Supreme Court. When that appeal failed in 1961, Kameny co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., which battled anti-gay discrimination in general and the federal government's exclusionary policies in particular. It was the first gay rights organization in the nation’s capital.

In 1963, Kameny became the first openly gay person to testify before Congress. He did so in defense of Mattachine after Congressman John Dowdy of Texas introduced a bill, H.R. 5990, to try to revoke the organization's permit to operate by amending the existing D.C. Charitable Solicitations Act. Dowdy’s bill stipulated that before granting a fundraising license, the D.C. Board of Commissioners had to certify that the grantee would "benefit or assist in promoting the health, welfare, and the morals of the District of Columbia."

Kameny went on to become a chief organizer of the first gay rights demonstrations in the nation’s capital. In 1965, he led protests at the White House, the Pentagon, and the Civil Service Commission. To remind the country that gay Americans lacked basic civil rights, Kameny and Mattachine joined with other gay rights organizations for "annual reminder" protests at Independence Hall in Philadelphia each Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969. Kameny later ran to become D.C.’s delegate to Congress. He lost the election, but his attempt marked the first time an openly gay candidate had run for Congress.

In 1975, the Civil Service Commission announced new rules stipulating that gay people could no longer be barred or fired from federal employment because of their sexuality.

Select pages of this document are shown. Find the entire court case in the National Archives Catalog.

Kameny sought to have the termination of his employment overturned by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. That court did not rule in his favor. The documents shown here are his appeal of that lower court decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Ulitmately, Kameny appealed his firing all the way to the Supreme Court. When that appeal failed in 1961, Kameny co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., which battled anti-gay discrimination in general and the federal government's exclusionary policies in particular. It was the first gay rights organization in the nation’s capital.

In 1963, Kameny became the first openly gay person to testify before Congress. He did so in defense of Mattachine after Congressman John Dowdy of Texas introduced a bill, H.R. 5990, to try to revoke the organization's permit to operate by amending the existing D.C. Charitable Solicitations Act. Dowdy’s bill stipulated that before granting a fundraising license, the D.C. Board of Commissioners had to certify that the grantee would "benefit or assist in promoting the health, welfare, and the morals of the District of Columbia."

Kameny went on to become a chief organizer of the first gay rights demonstrations in the nation’s capital. In 1965, he led protests at the White House, the Pentagon, and the Civil Service Commission. To remind the country that gay Americans lacked basic civil rights, Kameny and Mattachine joined with other gay rights organizations for "annual reminder" protests at Independence Hall in Philadelphia each Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969. Kameny later ran to become D.C.’s delegate to Congress. He lost the election, but his attempt marked the first time an openly gay candidate had run for Congress.

In 1975, the Civil Service Commission announced new rules stipulating that gay people could no longer be barred or fired from federal employment because of their sexuality.

Select pages of this document are shown. Find the entire court case in the National Archives Catalog.

Transcript

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT__________

NO. 15,596

___________

FRANKLIN EDWARD KAMENY, Appellant

v.

WILBER M. BRUCKER, et al, Appellees

_____________

Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia

________________

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

________________

This is an appeal docketed February 29, 1960 under the provisions of Title 28, Section 1291 U.S. Code, from an Order of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia entered December 28, 1959 granting summary judgment to the defendants appellees herein. Notice of Appeal was filed January 22, 1960.

[pages omitted]

ARGUMENT

A. The Court erred in granting the motion for summary judgment as to appellee Brucker since there was a genuine issue as to a material fact.

1. The issue was, did plaintiff-appellant deliberately and intentionally falsify his answers to Items 33 and 34 in the Standard Form 57?

a. "Disorderly Conduct." [underlined] In his answers to Items 33 and 34 appellant properly revealed that he had been arrested and disclosed the time and place of the arrest. He described the charge not in the terms of the ordinance, but in words which he though properly described the alleged offense. In his affidavit appellant says that at the time he filled out the Form 57 he could not recall the exact working of the charge. He was not sure that he had ever heard it; he was certain that he had never seen it written down. In his affidavit he says that he was, of course, aware of what happened in San Francisco and had often heard like conduct referred to as "disorderly conduct". He says he used the words in good faith believing that "I was describing exactly the nature of the charge". He says that the words, in his mind, indicated a serious charge.

b. "Action Taken." [underlined] In his affidavit, appellant says that he specifically asked the probation officer how to answer such a question and was advised that he could answer it as he did and be truthful. He says he thought he was quoting the record.

c. Not willful, deliberate or intentional misinformation. [sentence underlined] Appellant certainly disclosed the incident fully and in his affidavit says that he expected the Civil Service Commission to investigate the incident. He made no effort to conceal or mislead. The "False" answer does not fall within the fraud ruling of Kolber [underlined] v. Gray [underlined], 93 U.S. App. D.C. 97; 207 F 2d 35. A false answer in a Form 57 must be a willing or intentional one to justify a separation, 5 FC.R. 2.104(4); Kolberg [underlined] v. Gray, [underlined] supra.

d. Appellant was not accorded his procedural rights by the Army Map Service [sentence underlined].

- 6 -

The charges against appellant, dated December 10, 1957 were signed "For the Commander" by "B. D. Hull. Civilian Personal Officer". (Ex. No. 1, J.A. ___)." The December 20, 1957 letter of decision was signed "For the Commander" by "B. D. Hull, Civilian Personal Officer". (Ex. No. 4, J.A. ___)." Appellant invoked the grievance procedure provided for in Civilian Personnel Regulation E 2. The Hearing Board was composed of the Commander and B. D. Hull, Civilian Personnel Officer. (Complaint Count I ss 7, J.A. __). Thus the charges were brought, initially decided and decided on appeal by the same two men. This is not due process.

C.P.R. E 2,1,4,b provides:

Complaints or grievance arising from the following types of decision or actions will be processed under the regulations with authority for final action vested in the commanding Officer. Hearings may be held at the commanding officer discretion, but the employee concerned will not be entitled to request a review, except as provided in (8) below. (The exceptions are not material to this case).

C.P.R. E a, 1, 2, 3, j provides under "Definitions":

Hearing. A formally convened meeting, or a series of meetings, at which an officially appointed, impartial disinterested group serves as a fact-finding body to develop pertinent testimony and evidence relating to a grievance case as a basis for recommending appropriate decision or action by the installation commander. (Ex. No. 6, J.A.__).

Appellant, having invoked the grievance procedure as a matter of right, and the Commander, having granted a hearing, was entitled under the C.P.R. provision to a hearing before an "impartial, disinterested group" "officially appointed" and "formally convened". He didn't get it. Under Watson v. U.S., 162 F. Supp. 755, appellant would be entitled to an order to reinstate because of the Army Map Service' failure to follow its own regulations, Service v. Dulles, 354, U.S. 363,386,387; Vitarelli v. Seaton,

- 7 -

359 U.S. 535,547; Graham v. Richmond, _U.S. App. D.C.__, 272 F. 2d , 522; U.S. ex rel Accardi v. Shaughnessy, 347 U.S. 260.

An order to the Secretary of the Army to reinstate appellant would be ineffective, however, in the face of the Civil Service Commission's finding of unsuitability. The granting of the motion as to appellee Brucker should, however, now be reversed by this Court.

B. The Court erred in granting the motion for summary judgement as to defendant-appellees Jones, Lawton and Gunderson since there was a genuine issue as to material fact.

1. The issue was, did the Civil Service Commission have anything in its files upon which to base a finding of immoral conduct?

a. What did the Commission have? Appellant, in his complaint and in his affidavit states that he had been informed by responsible personnel of the Commission that the Civil Service Commission had nothing in its files upon which to base a finding of unsuitability on the grounds of immoral conduct. The Commission had the record of the San Francisco arrest and the disposition of the case. In his affidavit, appellant describes the incident in the same manner as he had described it in his appeal to the Commission. He was not the actor. He did not even respond but was a victim. There was nothing in the incident which established immoral conduct as a matter of law. The Commission also had the transcripts of his interviews.

In his complaint and in his affidavit, appellant states that he has been told by employees of the Civil Service Commission that the Commission's section in declaring his unsuitable was not based upon any evidence in the files, nor upon anything he had said in the interviews, but rather upon the "tone and tenor" of his answers to the questions put to him by the investigators.

b. Refusal to answer questions. Appellant, in the interviews, refused to answer questions concerning his sexual behavior. This refusal has to be what the said employee meant by the "tone and tenor" of his

- 8 -

remarks. His refusal to answer questions on homosexuality were not admissions of immoral conduct, UIIman v. U.S., 350 U.S. 422. Use of the fifth Amendment or simply a refusal to answer any questions cannot be made grounds for disqualification for Federal employment as unsuitable, SIochower v. Board Of Higher Education, 350 U.S. 551; Graham v. Richmond, __U.S. App. D.C.__, 272 F. 2d 517,521, yet it is obvious that this is exactly what the Commission did. There is nothing in the law, Executive Orders or regulations which gives the Civil Service Commission the power or authority to disqualify an employee because he refuses to answer questions put to him by the Commissions Investigators.

c. Granting of the motion effectively denied appellant an opportunity to assert a denial of his Constitutional rights. Appellant was entitled to a denial of the motion for summary judgement and an opportunity to question Civil Service personnel under oath as to the information that was not in the files which might or might not show that appellant had been guilty of immoral conduct. He was entitled to an opportunity to examine and cross-examine witnesses under oath to find out what this "immoral conduct" was. If the San Francisco incident is all that the Commission has appellant would be entitled to an order reinstating him. Implicit in the Commission's finding, of course, is a conclusion that appellant is a homosexual and an unwritten rule that it is "immoral conduct" to be a homosexual. Appellant was entitled to find out, by a trial of the issues, whether this was the basis for the Commission's finding. If this could have been established by evidence adduced at a trial, then appellant would have been in a position to challenge the constitutionally of an unwritten rule that one is guilty of "immoral conduct" if he is a homosexual, and is unsuitable for Federal employment because he is a homosexual. Granting of the motion denied appellant this opportunity. Such an arbitrary, discriminatory and unreasonable rule of disqualification of Federal employment violates due process, Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183. In that case the Supreme Court struck

- 9 -

down a so-called 'loyalty oath' because it based employability solely on the fact of membership in certain organizations. The Court pointed out that membership itself may be innocent and held that the classification of innocent and guilty together was arbitrary. In SIochower, supra, the Court said that the Wieman case "rests squarely on the proposition that 'constitutional protection does extend to the public servant whose exclusion pursuant protection does extend to the public servant whose exclusion pursuant to a statute is patently arbitrary or discriminatory'". Proof, or even a tacit admission, that a person is a homosexual does not, standing alone, prove that he has been guilty of immoral conduct. Disqualification of homosexuals for employment by the Government is arbitrary, discriminatory, and unreasonable, and denies to each member of the group (sizable, it is said) equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

C. Court may review firing and finding of unsuitability. Even where prescribed procedures are followed meticulously (as they were not by the Army) the Courts will review and reverse firings on a showing that the firing was an abusive of discretion, or capricious, as would be the case were it established that appellant did not intend to deceive and that there was no evidence of immoral conduct in the Commission's files, Gadaden v. U.S., 78 F. Supp. 126, 111, Ct. CI. 487; 100 F. Supp. 455; Novogroski v. U.S. (Ct. CI. 1957) 153 F. Supp. 421; Eclov v. U.S. 137 Ct. CI. 341; v. U.S., Knotts v. U.S., 121 F. Supp. 630; 128 Ct. CI. 489.

Conclusion

Since genuine issues as to material facts exist, and procedural rights granted to appellant by CPR E2 have been violated, and the Court may review firings and findings of unsuitability when a showing of abuse of discretion has been made as here, and since the granting of appellees' motion deprived appellant of his rights and protection under the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, the decision of the lower court should be reversed and the case remanded for a trial of the issues.

Respectfully submitted,

[signature]

BYRON N. SCOTT

Attorney for Appellant

517 Wyatt Building

Washington 5, D. C.

[pages omitted]

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 15,596 September Term, 1959.

Franklin Edward Kameny, Appellant,

v.

Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellees.

Civil 1628-59

[stamp] United States Court of Appeals For the District of Columbia Circuit FILED JUN 23 1960 Joseph W. Stewart CLERK

Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

Before: Wilbur K. Miller, Danaher and Bastian, Circuit Judges.

JUDGMENT

This cause came on to be heard on the record on appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, and was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof It is ordered and adjudged by this Court that the order of the District Court appealed from in this cause be, and it is hereby, affirmed.

Per Curiam.

Dated: JUN 23 1960

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Courts of Appeals.

National Archives Identifier: 28360662

Full Citation: Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee; 1960; Case No. 15596; General Appellate Jurisdiction Case Files, 1893 - 1996; Records of the U.S. Courts of Appeals, Record Group 276; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/kameny-v-brucker, April 23, 2024]Activities that use this document

- The Long Struggle for LGBTQ+ Civil Rights

Created by the National Archives Education Team

Rights: Public Domain, Free of Known Copyright Restrictions. Learn more on our privacy and legal page.