In late 1863, President Abraham Lincoln and Congress began to consider the question of how the Union would be reunited if the North won the Civil War. In December, President Lincoln proposed a reconstruction program that would allow Confederate states to establish new state governments after 10 percent of their male population took loyalty oaths and the states recognized the permanent freedom of formerly enslaved people.

Several congressional Republicans thought Lincoln’s 10 percent plan was too lenient. Senator Benjamin F. Wade, of Ohio, and Representative Henry Winter Davis, of Maryland, proposed a more stringent plan in February 1864.

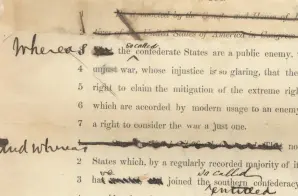

The Wade-Davis Reconstruction Bill would also have abolished slavery, but it required that 50 percent of a state’s White males take a loyalty oath to the United States (and swear they had never assisted the Confederacy) to be readmitted to the Union. Only after taking this “Ironclad Oath” would they be able to participate in conventions to write new state constitutions.

Congress passed the Wade-Davis Bill, but President Lincoln chose not to sign it, killing the bill with a pocket veto. Lincoln continued to advocate tolerance and speed in plans for the reconstruction of the Union in opposition to Congress.

After Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, however, Congress had the upper hand in shaping federal policy toward the defeated South and imposed the harsher reconstruction requirements first advocated in the Wade-Davis Bill. Some of the policies included in this bill were implemented in a series of four Reconstruction Acts (1867-1868), which were passed into law after Congress overrode the vetoes of President Andrew Johnson.