Following the Toy Safety Act, consumers continued to write to the Food and Drug Administration—and then the Consumer Product Safety Commission—about harmful playthings, calling on the U.S. bureaucracy to remove these goods from the market. Despite the work of government agencies to outlaw specific toys and to set new standards for safe design, familiar hazards continued to appear.

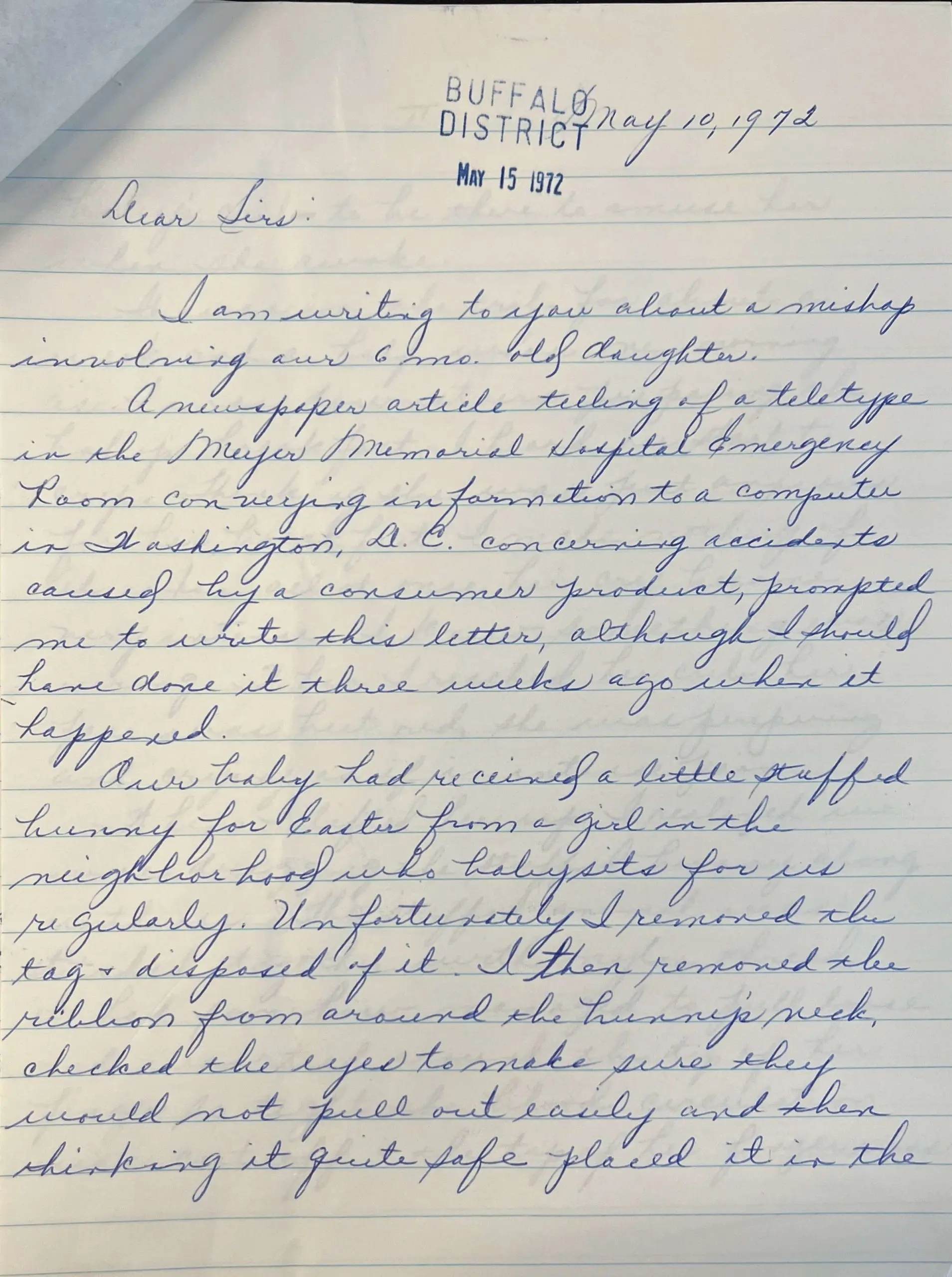

On May 10, 1972, Evelyn Buckley of Buffalo, New York, recounted a worrisome accident involving another stuffed Easter bunny. After checking that the doll’s eyes were securely attached to its head and taking off the ribbon around its neck, she decided the toy was “quite safe” and gave the rabbit to her infant daughter. A week-and-a-half later, Buckley heard the baby crying in her crib and found a stray nylon thread wrapped so tightly around her finger that a friend had to cut the string with nail clippers. “The very frightening part,” she reflected, “is that a large amount of the thread had pulled loose, enough so that it could have just as easily wrapped around the neck.”

This letter and dozens of others were sent to Federal agencies, especially the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). They serve as invaluable resources for learning about the toy safety crisis of the 1960s and 1970s. The troubling experiences of children and their families not only showcased the hidden risks of contemporary toys but also contributed to new laws regulating the safety of consumer products.