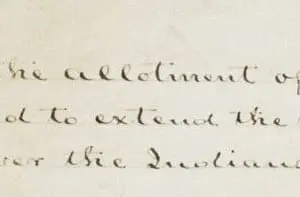

This “Act to Provide for the Allotment of Lands in Severalty to Indians on the Various Reservations” emphasized the treatment of Native Americans as individuals rather than as members of tribes.

It was different than the earlier Federal Indian policy (1870 to 1900) of removal, treaties, reservations, and war. This new policy sought to break up reservations by granting land allotments to individual Native Americans and encouraging them to take up agriculture.

It was reasoned that if a person adopted “White” clothing and ways, and was responsible for their own farm, they would gradually drop their “Indian-ness” and be assimilated into White American culture. Then it would no longer be necessary for the government to oversee Indian welfare in the paternalistic ways it had previously done, including providing meager annuities, with American Indians treated as dependents.

The Dawes Act, named for its author, Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, and also known as the General Allotment Act, authorized the President to break up reservation land, which was held in common by the members of a tribe, into small allotments to be parceled out to individuals. Native Americans registering on a tribal “roll” were granted allotments of reservation land.

The purpose of the Dawes Act, and the subsequent acts that extended its initial provisions, was purportedly to protect American Indian property rights, particularly during the land rushes of the 1890s. But in many instances the results were vastly different. The land allotted to individuals included desert or near-desert lands unsuitable for farming. In addition, the techniques of self-sufficient farming were much different from their tribal way of life. Many did not want to take up agriculture, and those who did want to farm could not afford the tools, animals, seed, and other supplies necessary to get started.

There were also problems with inheritance. Often young children inherited allotments that they could not farm because they had been sent away to boarding schools. Multiple heirs also caused a problem; when several people inherited an allotment, the size of the holdings became too small for effective farming. Tribes were also often underpaid for the land allotments, and when individuals did not accept the government requirements, their allotments were sold to non-Native individuals, causing American Indian communities to lose vast acreage of their tribal lands.

Some groups were exempt from the law: Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Seminoles; Osage, Miamies and Peorias; Sacs and Foxes; those “in the Indian Territory”; the Seneca Nation of New York Indians in the State of New York; and “that strip of territory in the State of Nebraska adjoining the Sioux Nation on the south.”

Subsequent events, however, extended the act’s provisions to these groups as well. In 1893, President Grover Cleveland appointed the Dawes Commission to negotiate with the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles, who were known as the Five Civilized Tribes. As a result of these negotiations, several acts were passed that allotted a share of common property to members of the Five Civilized Tribes in exchange for abolishing their tribal governments and recognizing state and Federal laws. In order to receive the allotted land, members were to enroll with the Office of Indian Affairs (later renamed the Bureau of Indian Affairs [BIA]). Once enrolled, the individual’s name went on the “Dawes Rolls.” This process assisted the BIA and the Secretary of the Interior in determining the eligibility of individual members for land distribution.

The Dawes Act is a part of America’s 100 Docs, an initiative of the National Archives Foundation in partnership with More Perfect that invites the American public to vote on 100 notable documents from the holdings of the National Archives. Visit 100docs.vote today.