Opening Statement of the Hoey Committee Hearings

Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

A National Archives Foundation educational resource using primary sources from the National Archives

Published By:

Historical Era:

Thinking Skill:

Bloom’s Taxonomy:

Grade Level:

This activity would work well for units that include the civil rights movements of the 1960s, or for specific units on LGBTQ+ (LGBT, LGBTQIA) history. For grades 8-12. Approximate time needed is 40 minutes.

Note: Students will see commonly used words from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s in these primary sources: “homosexual” and “Negro” – rather than today’s more acceptable terms “gay” and “Black.” This is explained in the activity’s instructions, but historical terminology and changes in language over time may be something you want to discuss with students either before or after the activity.

To begin, display the activity for students and select one primary source with which to model document analysis. Then ask students to begin the activity working individually or in pairs. They should read through each source, then place them all in chronological order. Remind students to carefully examine each primary source by clicking on the orange “open in new window” icon to see it more closely (this is also necessary to watch the video) and to read the historical context provided for each one.

Instruct students to analyze each historical source in full (and not just look for the date) because they should be thinking about (or writing down) the issues presented, how people tried to change things, and the successes of the movement in preparation for the follow-up questions.

The correct order for the sources is:

After the students complete the sequencing of the sources, they should click on “When You’re Done” and answer the questions provided. Conduct a full-class discussion based on these questions:

You may also wish to discuss with students what kinds of sources are missing from this activity that would be useful for understanding LGBTQ+ civil rights history. (All of these documents come from the holdings of the National Archives. At the National Archives, we hold documents and other records largely created by the Federal Government in the course of doing Federal business. The scope of our holdings is limited by this factor.)

In this activity, students will read and analyze 10 primary sources related to LGBTQ+ civil rights, then place them in chronological order. The activity will introduce students to a wide range of sources from LGBTQ+ civil rights history and help them understand the issues at different points in time, as well as when, how, and why changes occurred.

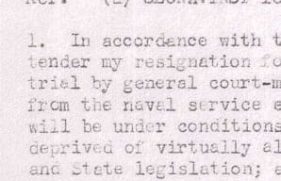

The sources range from the 1950 Hoey Committee opening statement during the Lavender Scare – a time when thousands of gay employees were fired or forced to resign from the Federal workforce because of their sexuality – to a 2015 phone call from President Barack Obama congratulating Jim Obergefell on his victory in the Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges, that legalized same-sex marriage in the United States.