Lincoln's Spot Resolutions

Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

A National Archives Foundation educational resource using primary sources from the National Archives

Published By:

Historical Era:

Thinking Skill:

Bloom’s Taxonomy:

Grade Level:

This activity can be used during a unit on manifest destiny or the Mexican-American War. For grades 7-12. Approximate time needed is 20-30 minutes.

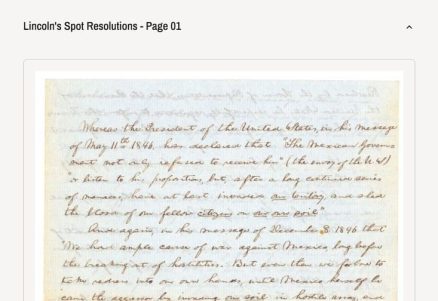

Ask students to begin the activity, working individually or in pairs. They will be instructed to read the Congressional resolution and to summarize Lincoln’s main points in their own words, page by page. If students are struggling to read the handwriting, they can click on “View Primary Source Details” to zoom in and access a transcription. Check in with students as needed to ensure they have identified the main idea of each of Lincoln’s eight resolutions.

When they have finished with the document, they should click on When You’re Done and respond to the following:

Discuss students’ responses and opinions. Provide the following additional background information as needed:

Prior to Texas’s independence, the Nueces River was recognized as the northern boundary of Mexico. Spain had fixed the Nueces as a border in 1816, and the United States ratified it in the 1819 treaty by which the United States had purchased Florida and renounced claims to Texas.

Even following Mexico’s independence from Spain, American and European cartographers fixed the Texas border at the Nueces. When Texas declared its independence, however, it claimed as its territory an additional 150 miles of land, to the Rio Grande. With the annexation of Texas in 1845, the United States adopted Texas’s position and claimed the Rio Grande as the border.

Mexico broke diplomatic relations with the United States and refused to recognize either the Texas annexation or the Rio Grande border. President James Polk sent special envoy John L. Slidell to propose cancellation of Mexico’s debt to United States citizens who had incurred damages during the Mexican Revolution, provided Mexico would formally recognize the Rio Grande boundary. Slidell was also authorized to offer the Mexican government up to $30 million for California and New Mexico.

Between Slidell’s arrival on December 6, 1845, and his departure in March 1846, the regime of President Jose Herrara was overthrown and a nationalistic government under General Mariano Paredes seized power. Neither leader would speak to Slidell. Paredes publicly reaffirmed Mexico’s claim to all of Texas.

On January 13, 1846, more than 3,500 U.S. troops commanded by General Zachary Taylor moved south under President Polk’s order, from Corpus Christi on the Nueces River to a location on the north bank of the Rio Grande. Advancing on March 8 to Point Isabel, the U.S. troops found that the settlement had been burned by fleeing Mexicans. By March 28, the troops were near the mouth of the Rio Grande across from the Mexican town of Matamoros.

Polk claimed the move was a defensive measure, and expansionists and Democratic newspapers in the United States applauded his action. Whig newspapers said that the movement was an invasion of Mexico rather than a defense of Texas. On April 25, Mexican cavalry crossed the Rio Grande and attacked a mounted American patrol, killing five, wounding 11, and capturing 47.

In Washington, President Polk, although unaware of the developments, had drafted a message asking Congress to declare war on Mexico on the basis of Mexico’s failure to pay U.S. damage claims and refusal to meet with Slidell. On May 9, Polk received Taylor’s account of the April 25 skirmish. Polk revised his war message, then sent it to Congress on May 11 asserting, “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon America’s soil.” On May 13, Congress declared war, with a vote of 40-2 in the Senate and 174-14 in the House.

Although Congress had declared war, it was not without reservation. An amendment was proposed, although defeated, to indicate that Congress did not approve of Polk’s order to move troops into disputed territory. Sixty-seven Whig representatives voted against mobilization and appropriations for a war.

Freshman Whig Congressman from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, questioned whether the “spot” where blood had been shed was really U.S. soil. His Spot Resolutions were not debated nor adopted by the House of Representatives, however.

Lincoln would not be reelected to the House, in part due to his opposition to the war. Ironically, later as President during the Civil War, Lincoln would greatly expand presidential war powers. Following the firing on Fort Sumter, he declared a naval blockade on his own authority.

This activity asks students to read, analyze, and summarize Abraham Lincoln’s Spot Resolutions, which he introduced in 1847 to protest the Mexican-American War during his only term in the House of Representatives.