Comparing Civil War Recruitment Posters

Compare and Contrast

Share to Google Classroom

Recommended Activity

Published By:

National Archives Foundation

Historical Era:

Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Thinking Skill:

Historical Analysis & Interpretation

Bloom’s Taxonomy:

Analyzing

Grade Level:

Middle School, High School

Suggested Teaching Instructions

Use this activity when studying the different perspectives on the recruitment of African Americans and the institution of slavery during a unit on the Civil War. It can provide an introduction to the relationship between military service, emancipation, and Union victory. For grades 7-12.

Prompt students to carefully examine the two documents with the discussion questions provided. Remind them to click on the magnifying glass for further detail.

- Who do you think created each of these posters. For what purpose?

- Who do you think is the intended audience?

- What does the creator of each poster hope the audience will do?

- Are the posters effective? Why or why not?

Ask students, after closely reading and analyzing the language in each poster, how the language used reflects the differences in attitude and perspective regarding African Americans in the Union and the Confederacy?

Share the following historical context, if necessary:

Explain that issues of emancipation and military service were intertwined from the onset of the Civil War. News from Fort Sumter set off a rush by free black men to enlist in U.S. military units. They were turned away, however, because a Federal law dating from 1792 barred them from bearing arms for the U.S. army (although they had served in the American Revolution and in the War of 1812).

The Lincoln administration wrestled with the idea of authorizing the recruitment of black troops, concerned that such a move would prompt the border states to secede. When Gen. John C. Frémont in Missouri and Gen. David Hunter in South Carolina issued proclamations that emancipated slaves in their military regions and permitted them to enlist, their orders were overturned.

But the increasingly pressing personnel needs of the Union Army pushed the Government into reconsidering the ban. On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, freeing slaves who had masters in the Confederate Army. Two days later, slavery was abolished in the territories of the United States, and on July 22 President Lincoln presented the preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet.

After the Union Army turned back Lee’s first invasion of the North at Antietam, MD, and the Emancipation Proclamation was subsequently announced, black recruitment was pursued in earnest. In May 1863, the Government established the Bureau of Colored Troops to manage the burgeoning numbers of black soldiers.

To the extent possible under law, National Archives Foundation has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to “Comparing Civil War Recruitment Posters”

Description

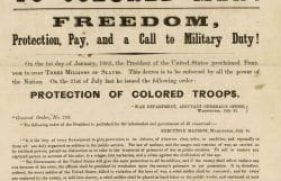

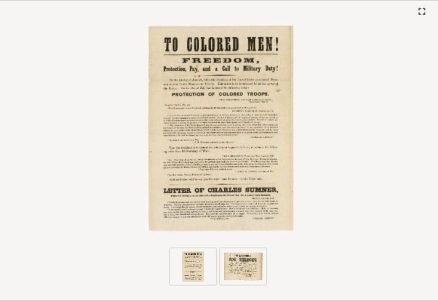

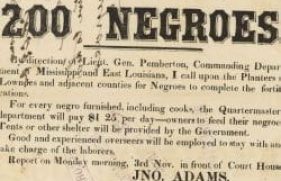

Students will compare and contrast military recruitment posters to analyze various perspectives regarding the role of African Americans during the Civil War. They will determine the purpose of each poster—one recruiting black men for the Union Army and one for the Confederacy—and analyze how the use of language conveys the intended message.

Share this activity with your students

Documents in this Activity

Broadside Titled, "Wanted! 200 Negroes"

Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)