Separation of Powers or Shared Powers

Weighing the Evidence

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

When the framers were crafting the Constitution, they enacted the principles of separation of powers and checks and balances to create a stable and free government. "Separation of powers" meant that our government would be divided into 3 branches with different roles, while checks and balances made the government "share power" between the branches to limit the power of each branch.Your job is to determine whether in practice the US government follows the model of “separation of powers” or “shared powers.” Analyze each document, note which branches are involved and how they interact, then place the document on the scale.

Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

Separation of Powers or Shared Powers

Weighing the Evidence

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Consider how each document does or does not support two opposing interpretations or conclusions. Fill in the topic or interpretations if they are not provided. To show how the documents support the different interpretations, enter the corresponding document number into the boxes near the interpretation. Write your conclusion response in the space provided. Interpretation 1

The relationship between the branches of the Federal government is best described as following the concept of "separation of powers."

The relationship between the branches of the Federal government is best described as following the concept of "separation of powers."

Relationship between the Legislative, Executive and Judicial Branches of the Federal Government

Interpretation 2

The relationship between the branches of the Federal government is best described as following the concept of "shared powers."

The relationship between the branches of the Federal government is best described as following the concept of "shared powers."

1

Activity Element

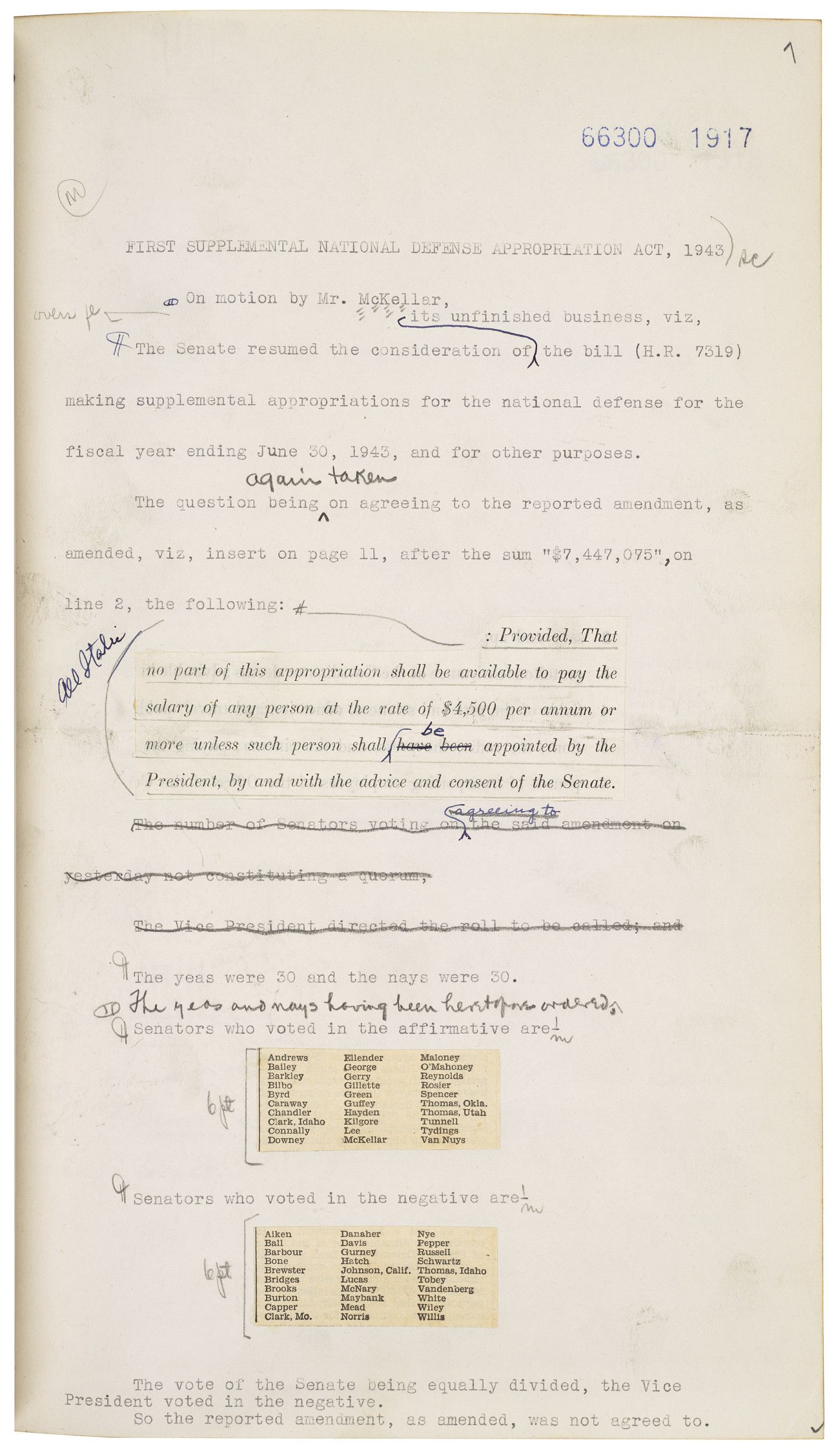

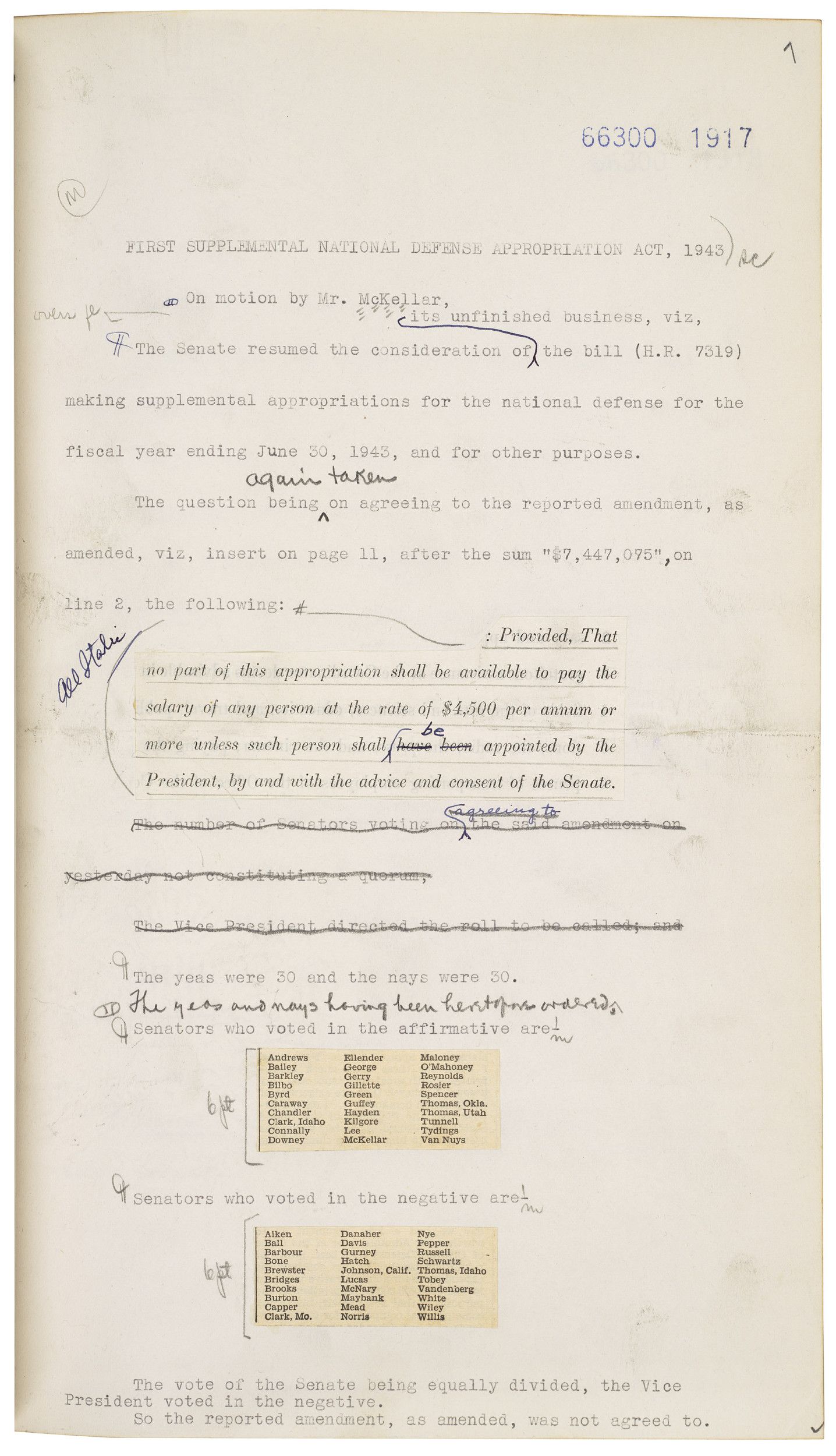

Senate Journal for the Second Session of the 77th Congress

Page 1

2

Activity Element

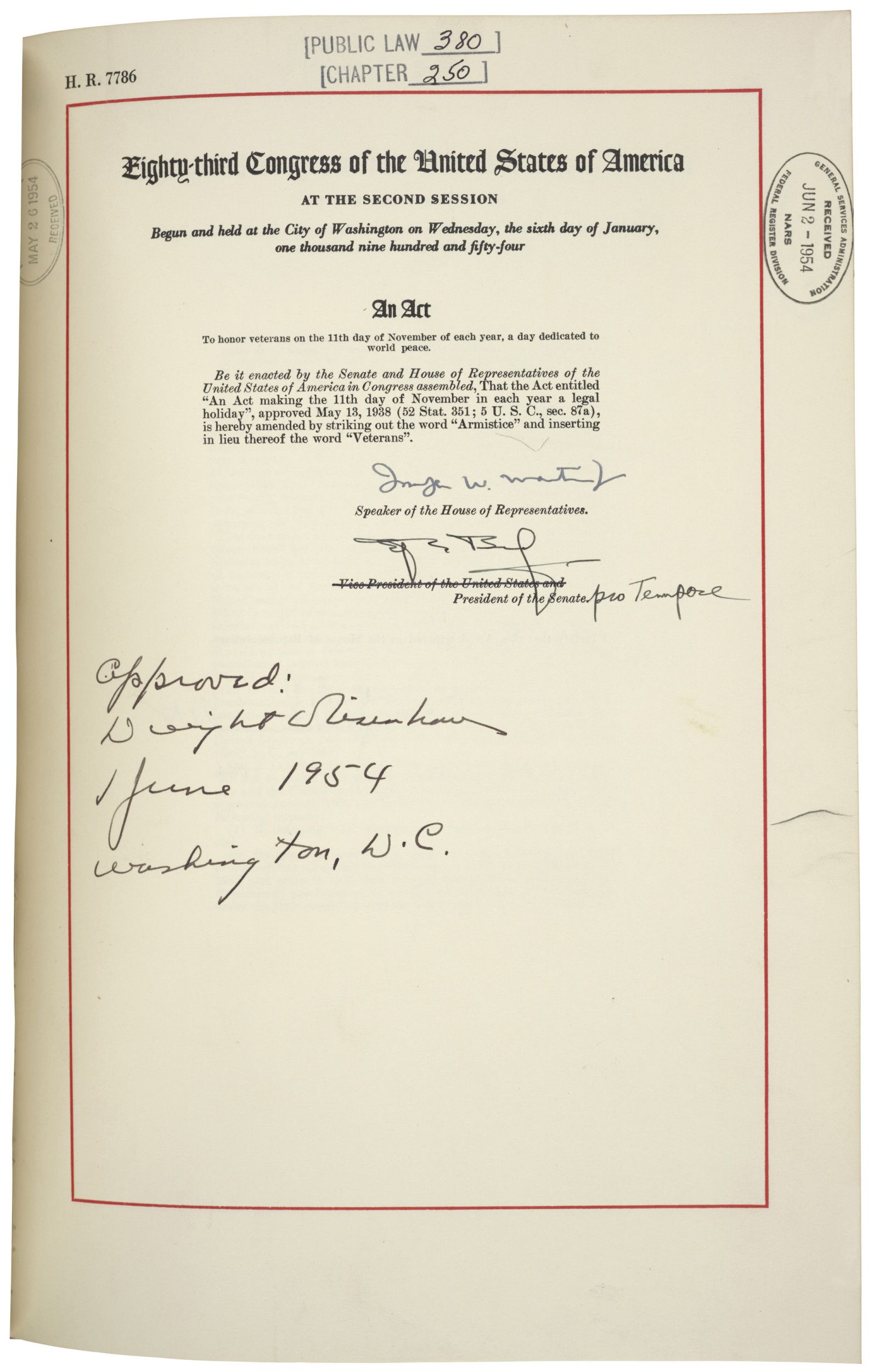

[Bill to Honor Veterans] House Resolution 7786 of the 83rd Congress

Page 1

3

Activity Element

Senate Resolution 301 of the 83rd Congress

Page 2

4

Activity Element

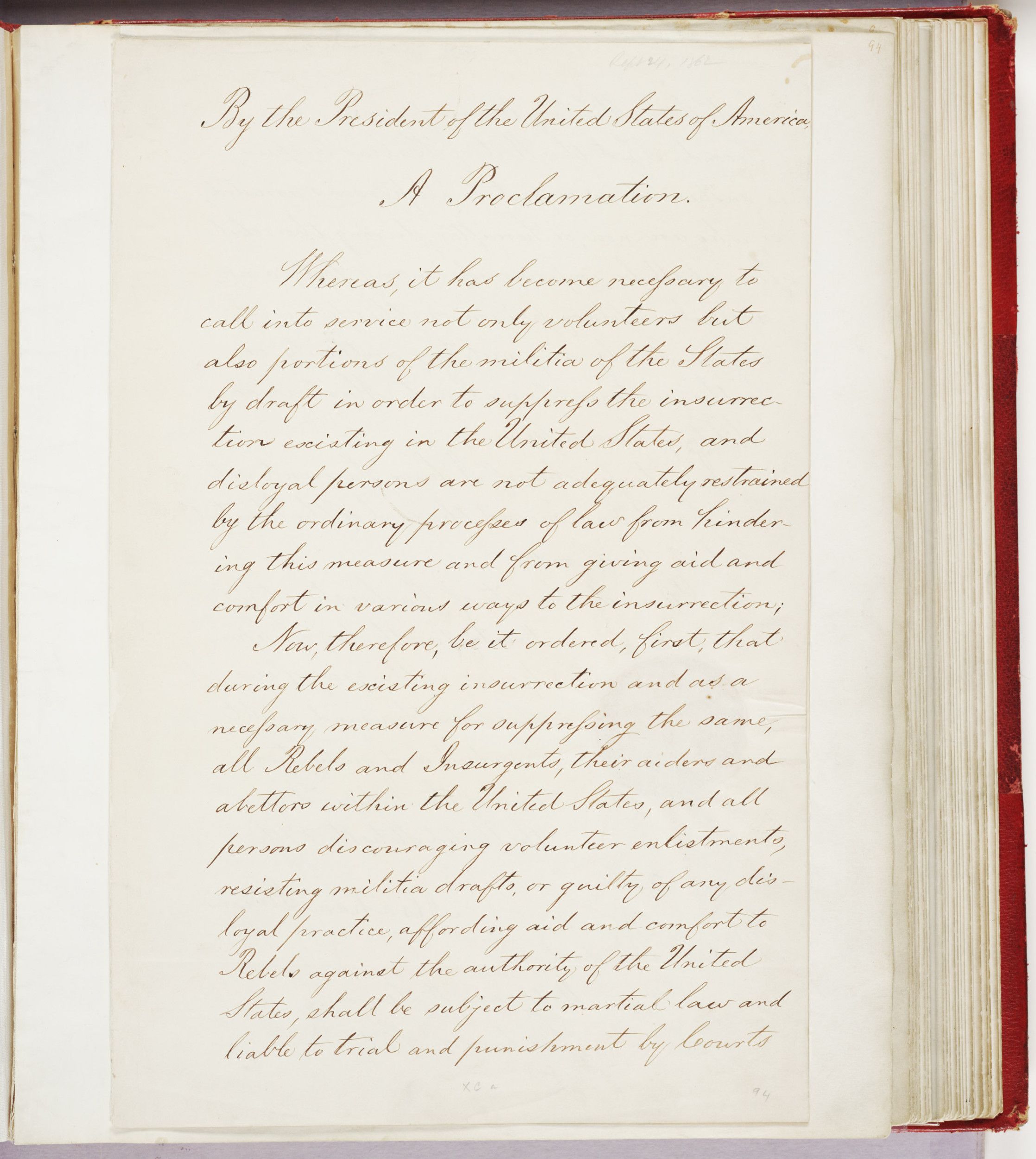

Presidential Proclamation 94 of September 24, 1862, by President Abraham Lincoln suspending the writ of Habeas Corpus.

Page 1

5

Activity Element

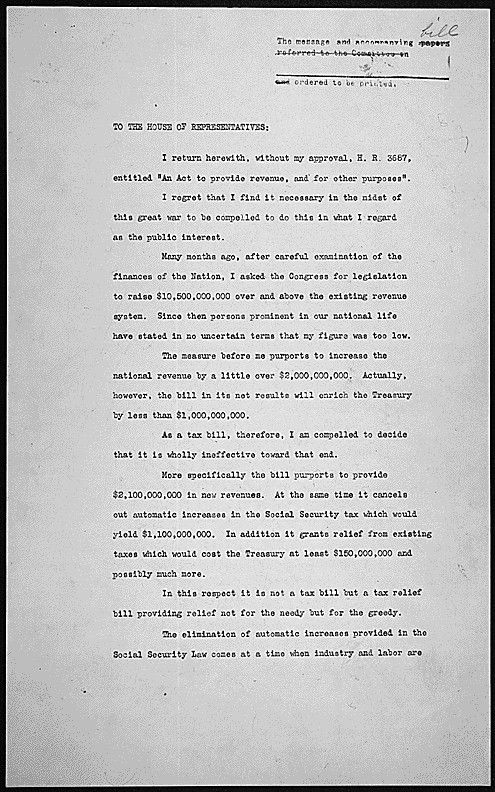

Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

Page 1

6

Activity Element

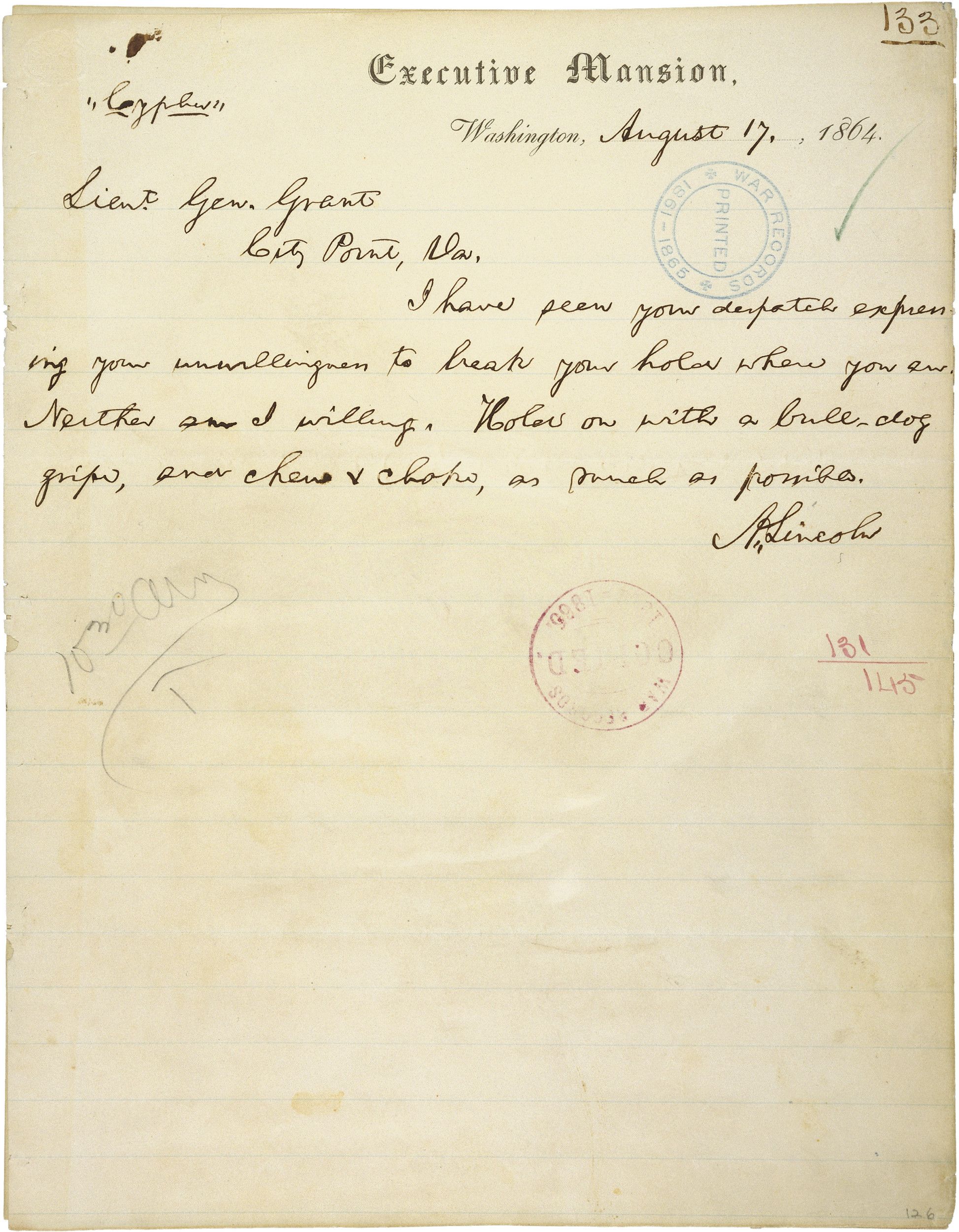

Telegram from Abraham Lincoln to Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant at City Point, Virginia

Page 1

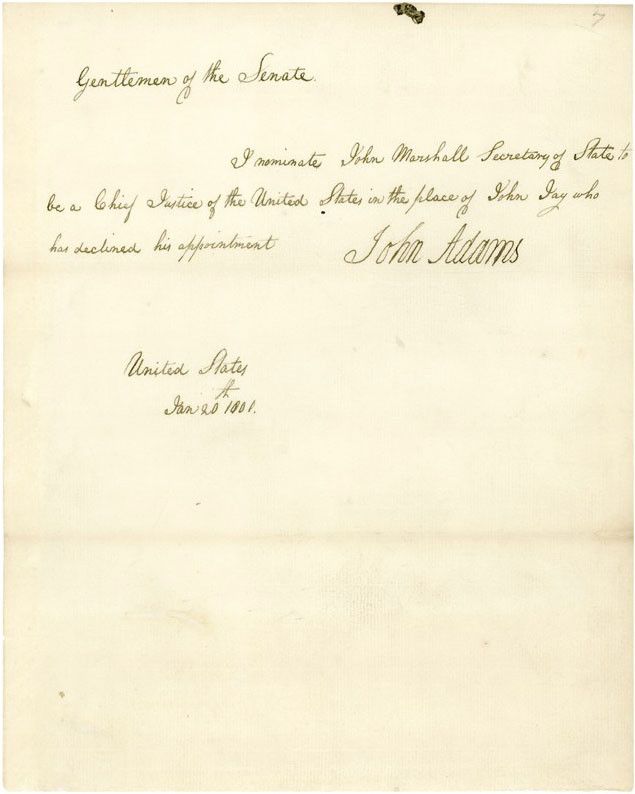

7

Activity Element

Message of President John Adams nominating John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

Page 1

8

Activity Element

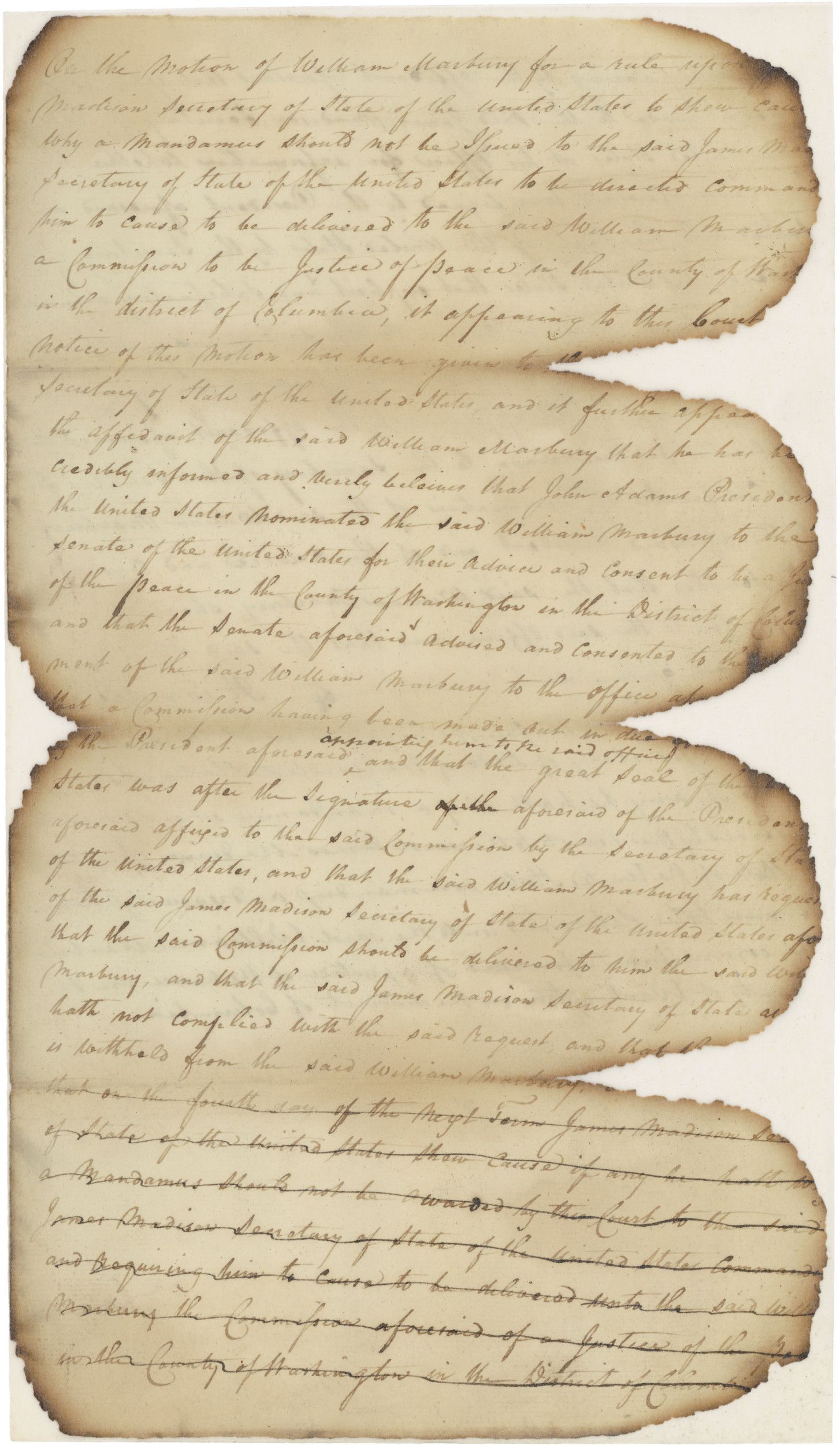

Draft of Motion Rule for Marbury v. Madison

Page 1

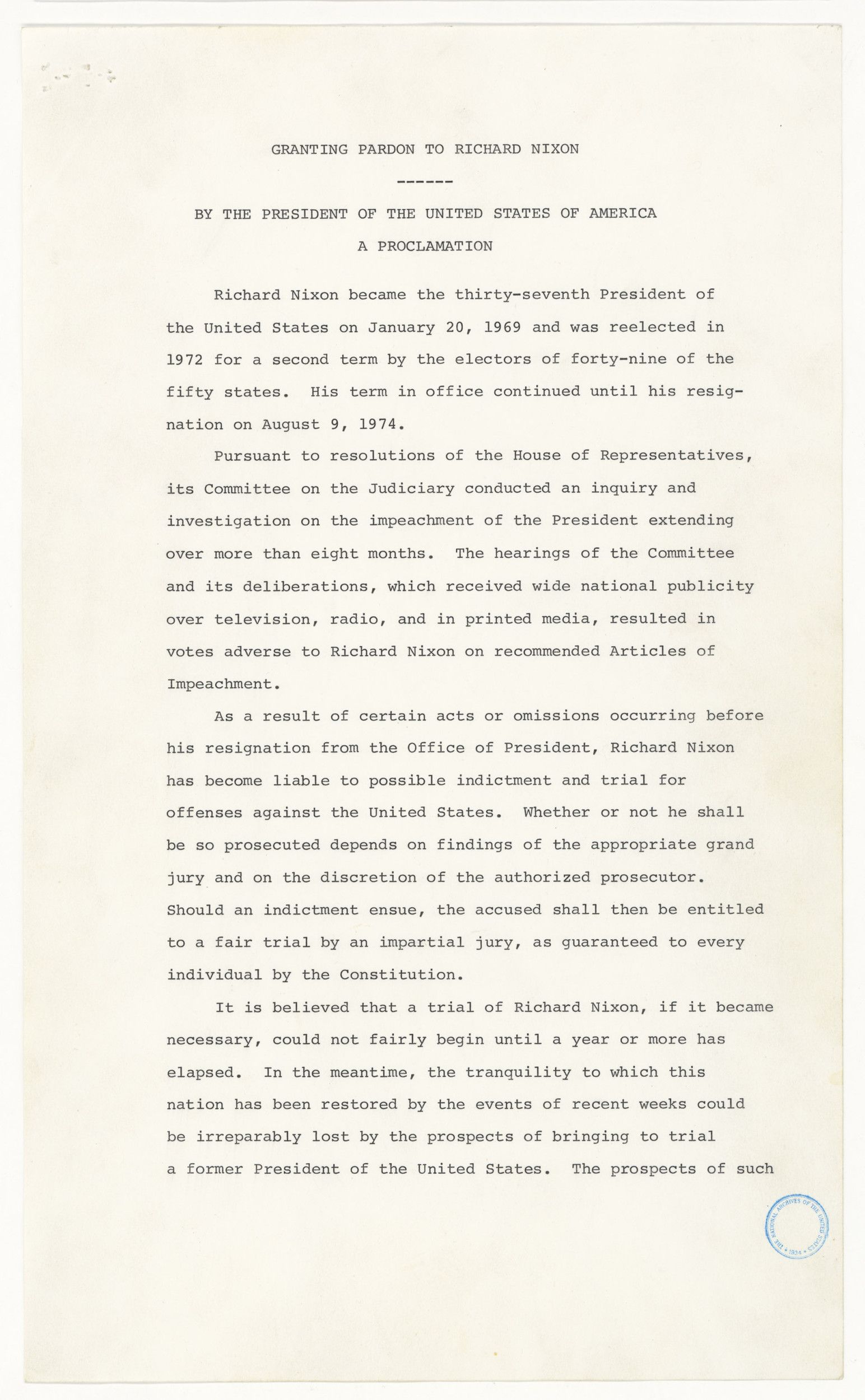

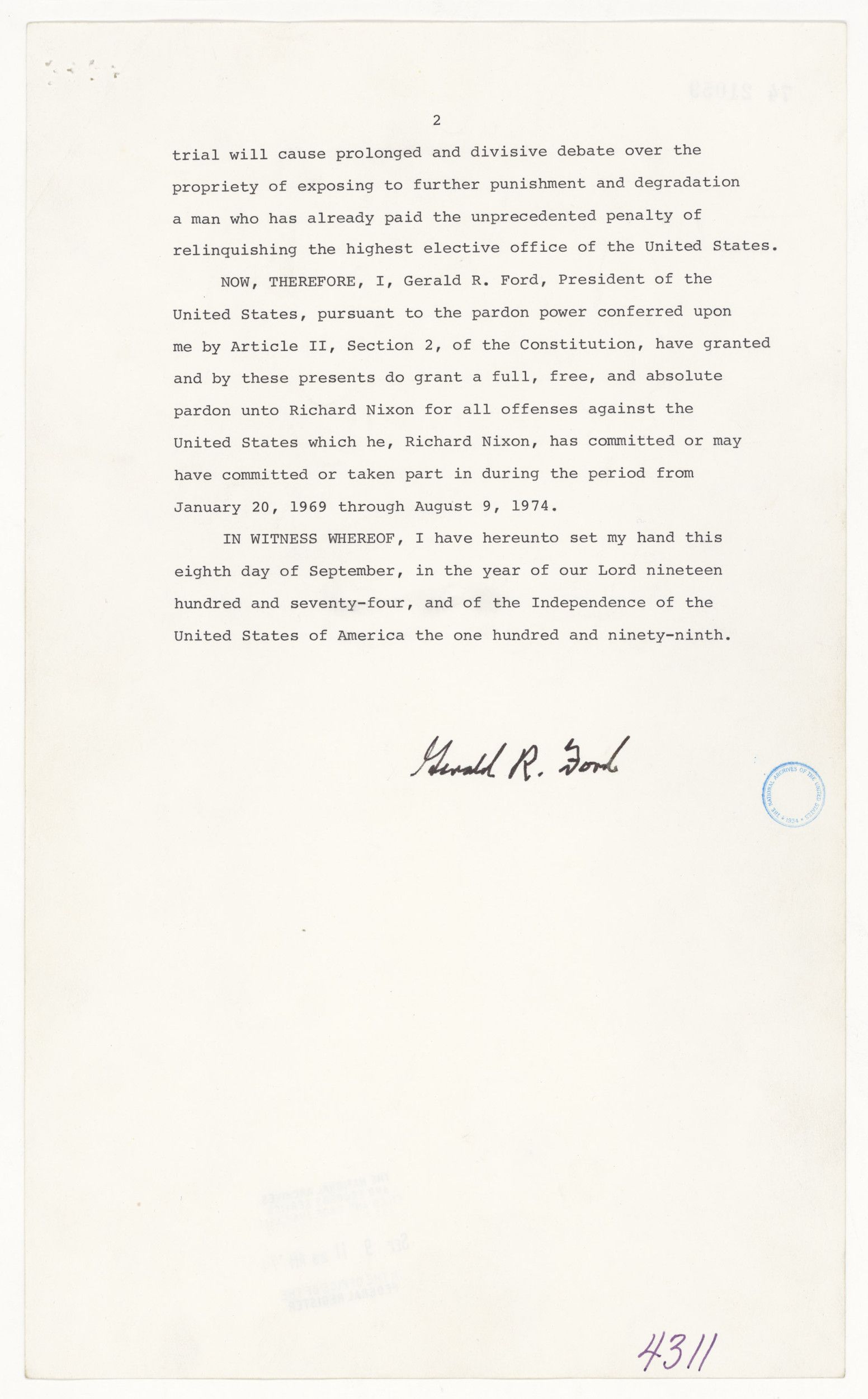

9

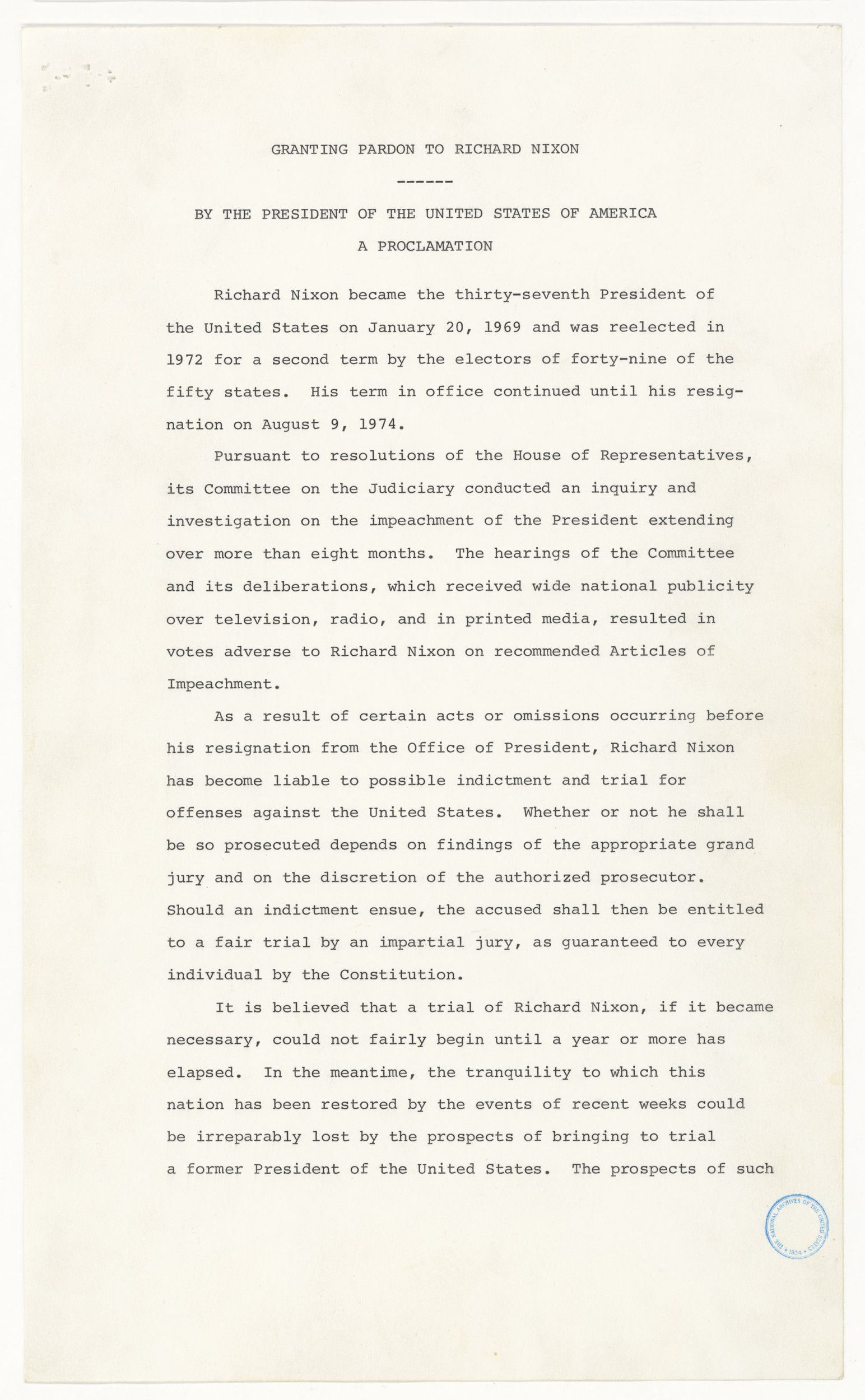

Activity Element

Presidential Proclamation 4311 of September 8, 1974, by President Gerald R. Ford granting a pardon to Richard M. Nixon.

Page 2

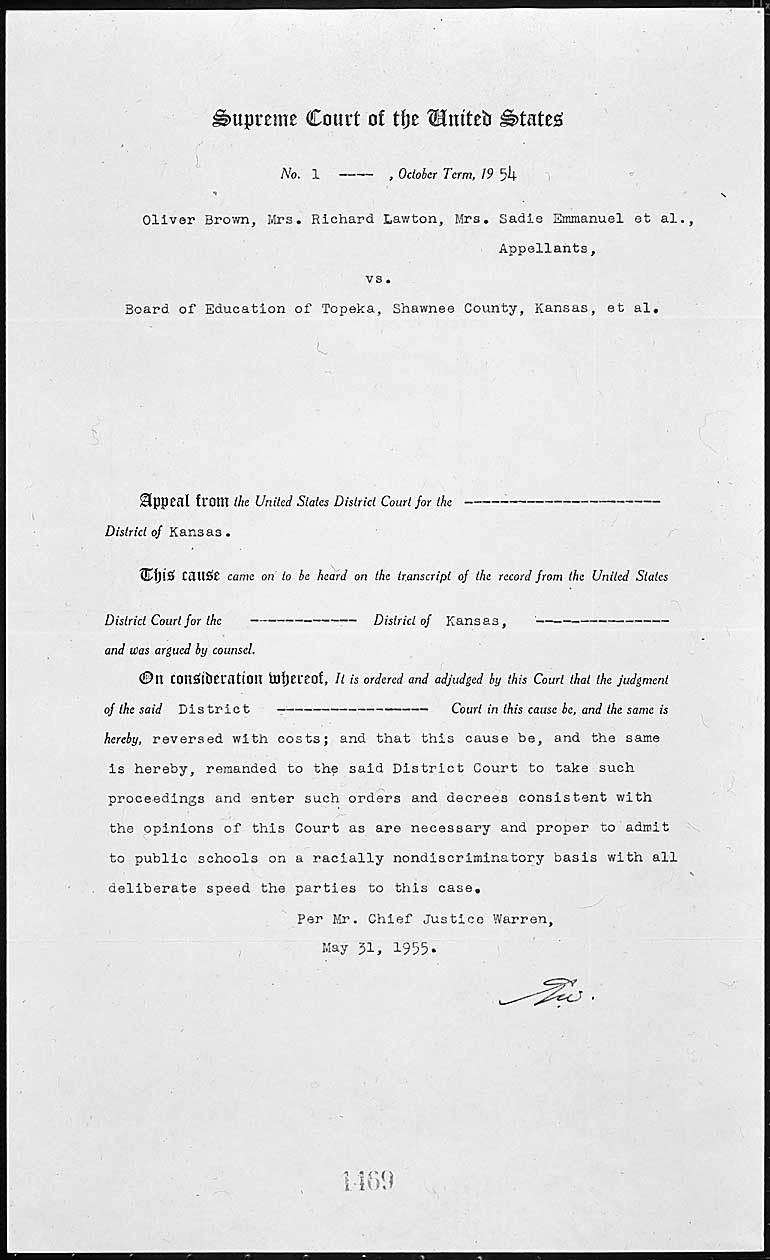

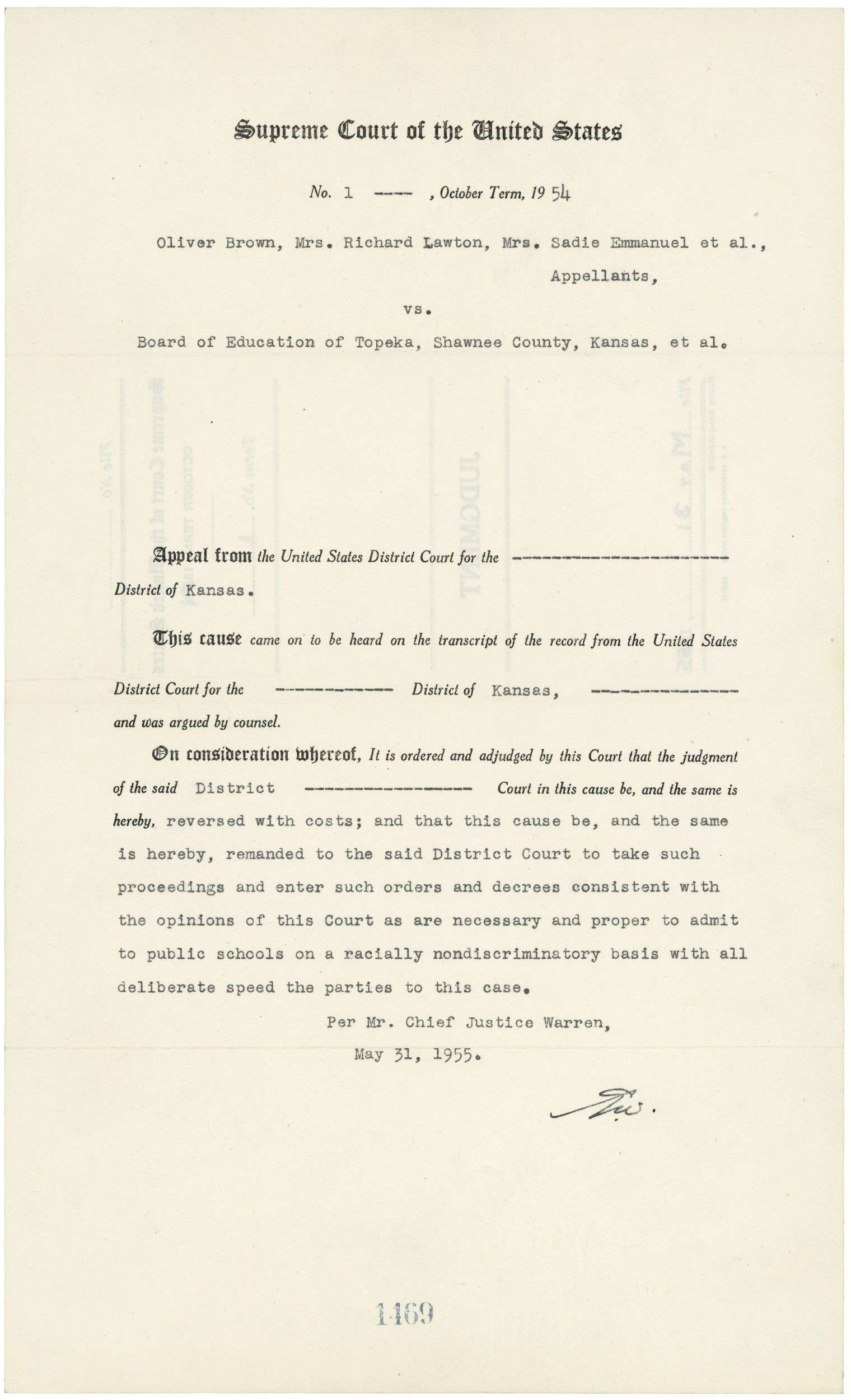

10

Activity Element

Judgment, Brown v. Board of Education

Page 2

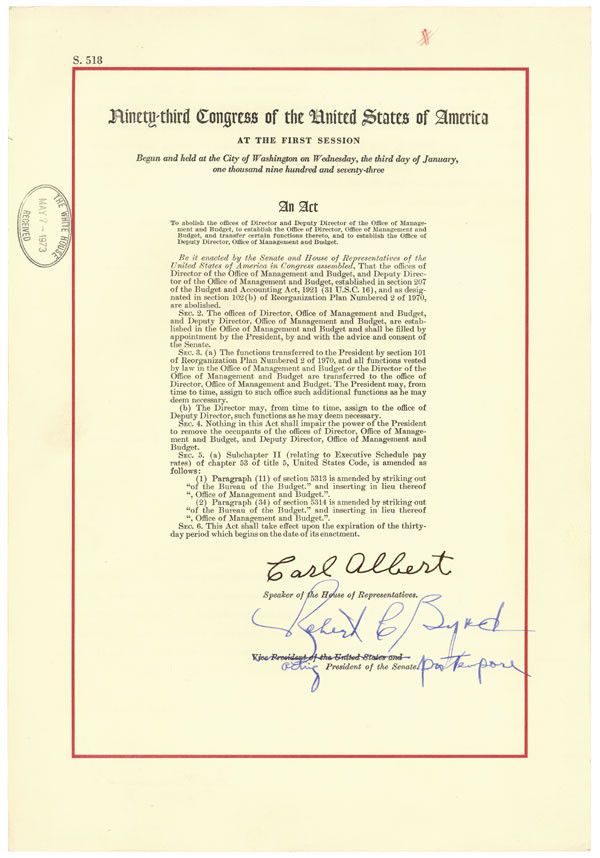

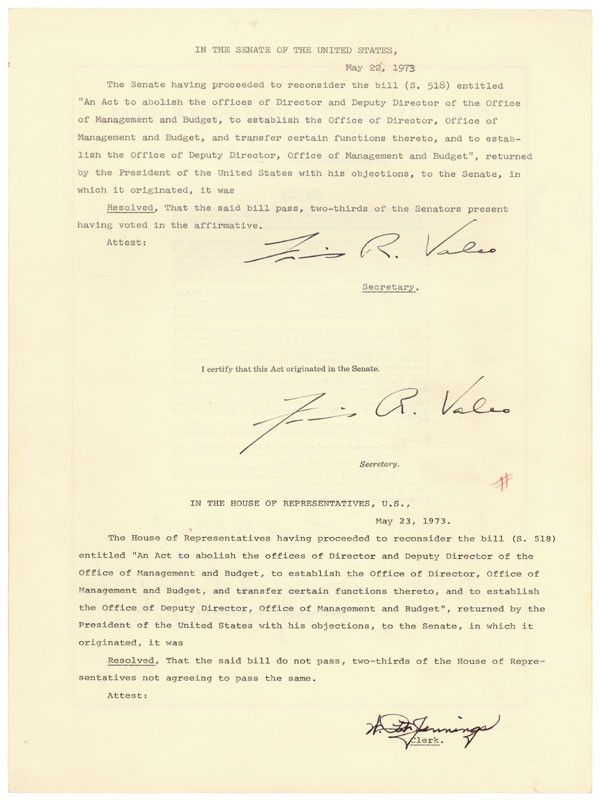

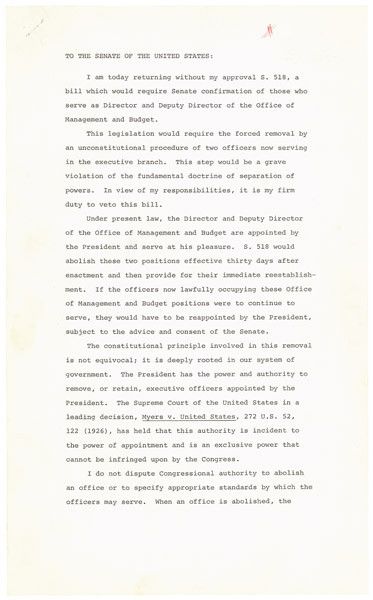

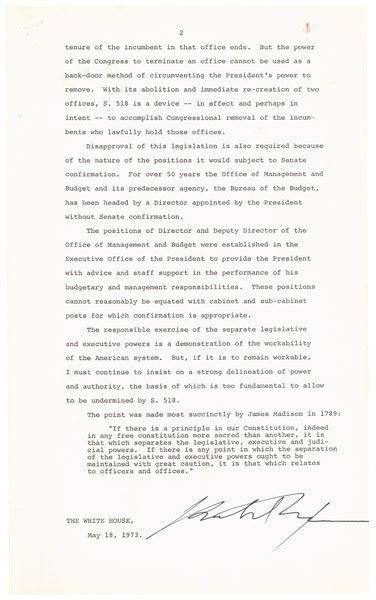

11

Activity Element

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, an Act to Abolish the Offices of the Director and Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget

Page 1

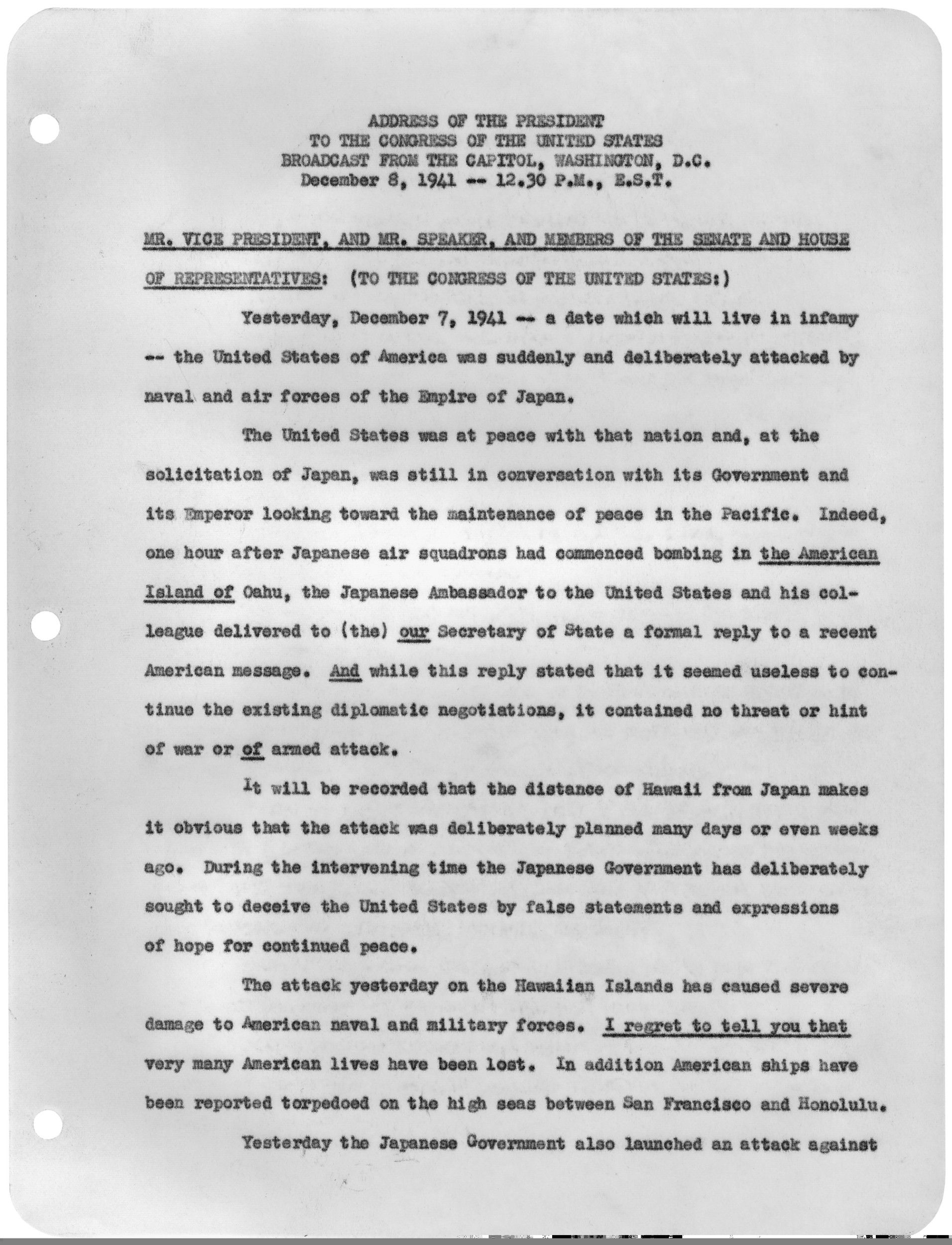

12

Activity Element

Transcript of Message to Congress Requesting Declaration of War Against Japan

Page 1

13

Activity Element

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1

14

Activity Element

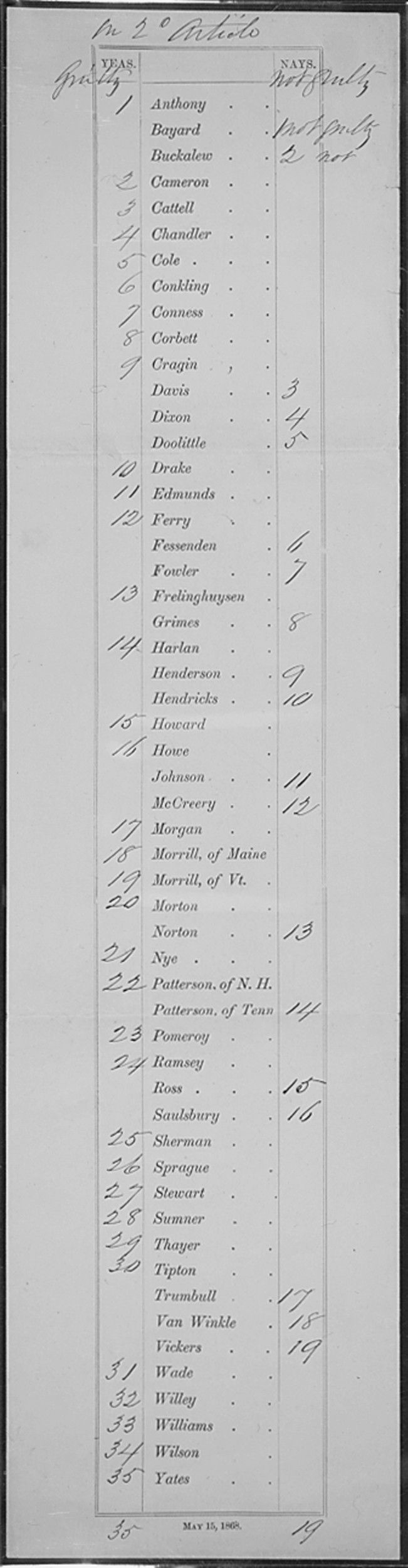

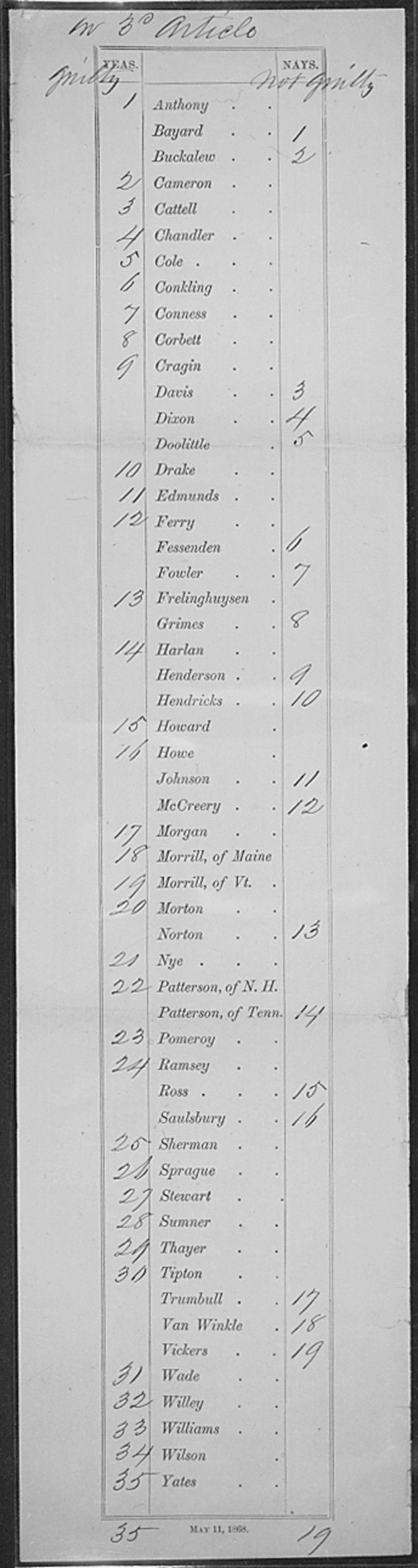

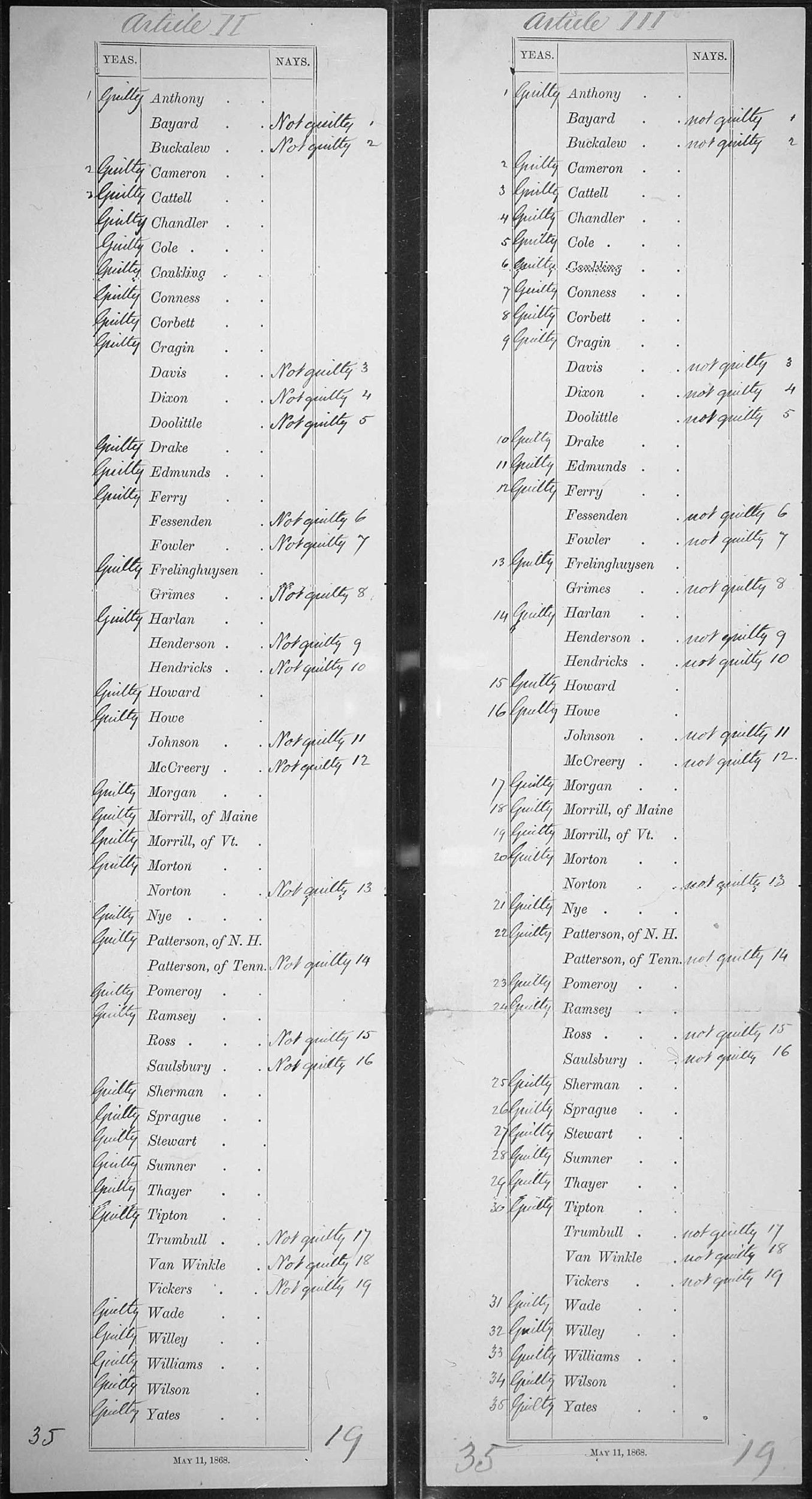

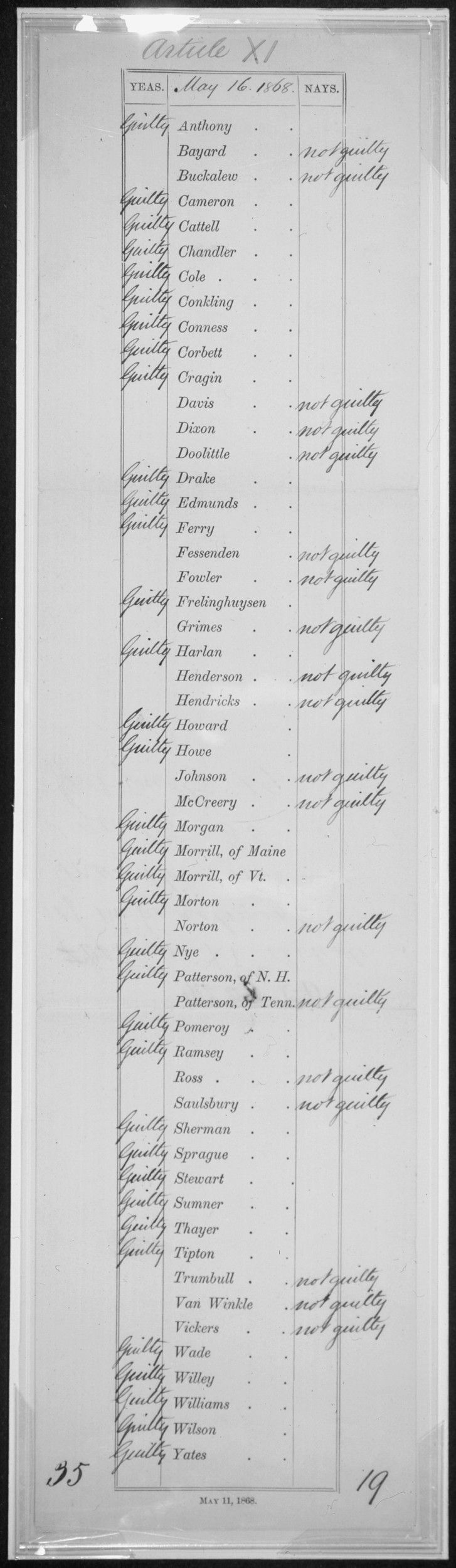

Roll call votes relating to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson on Articles II, III, and XI

Page 1

15

Activity Element

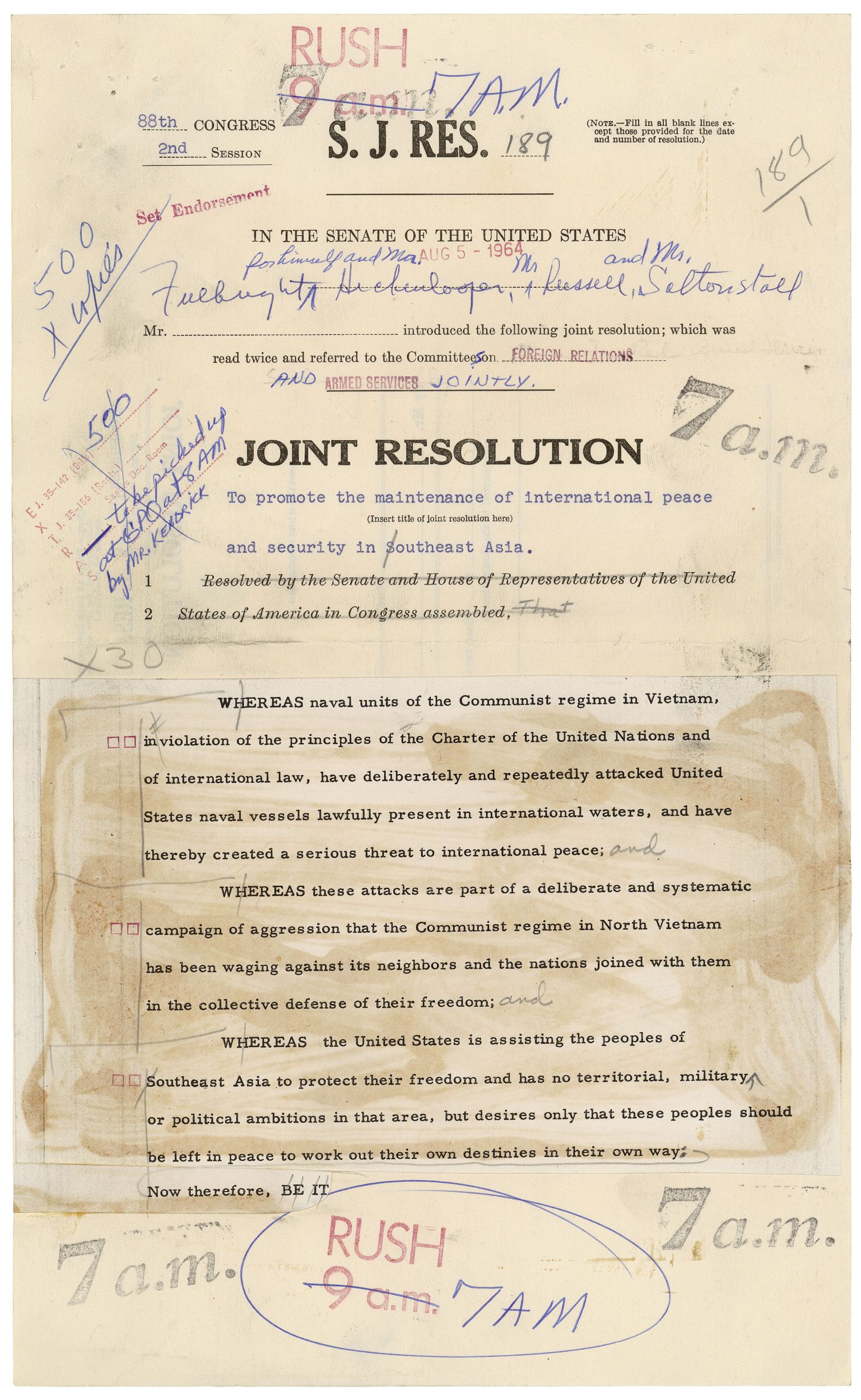

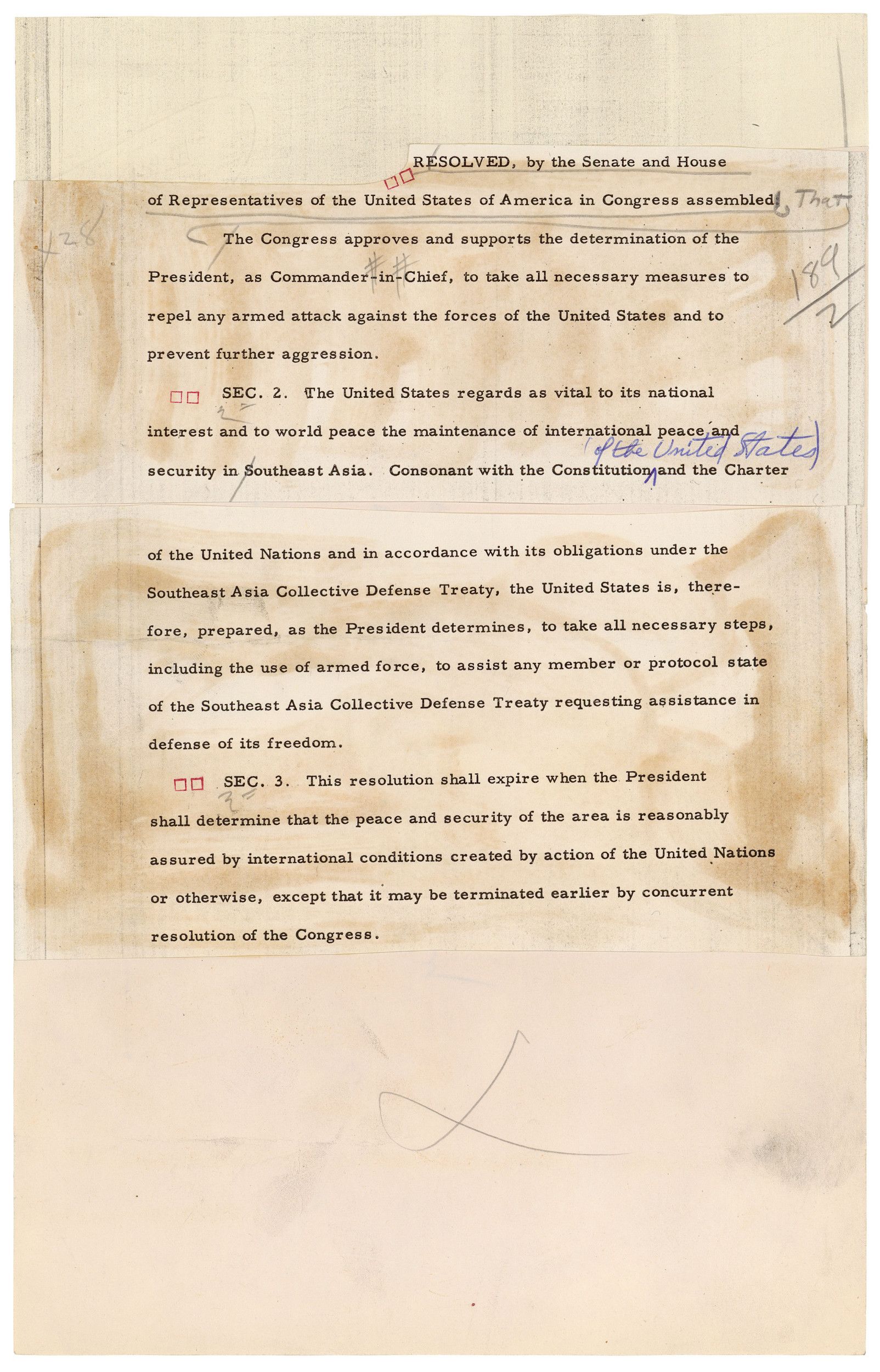

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Introduced, S.J. Res. 189

Page 2

16

Activity Element

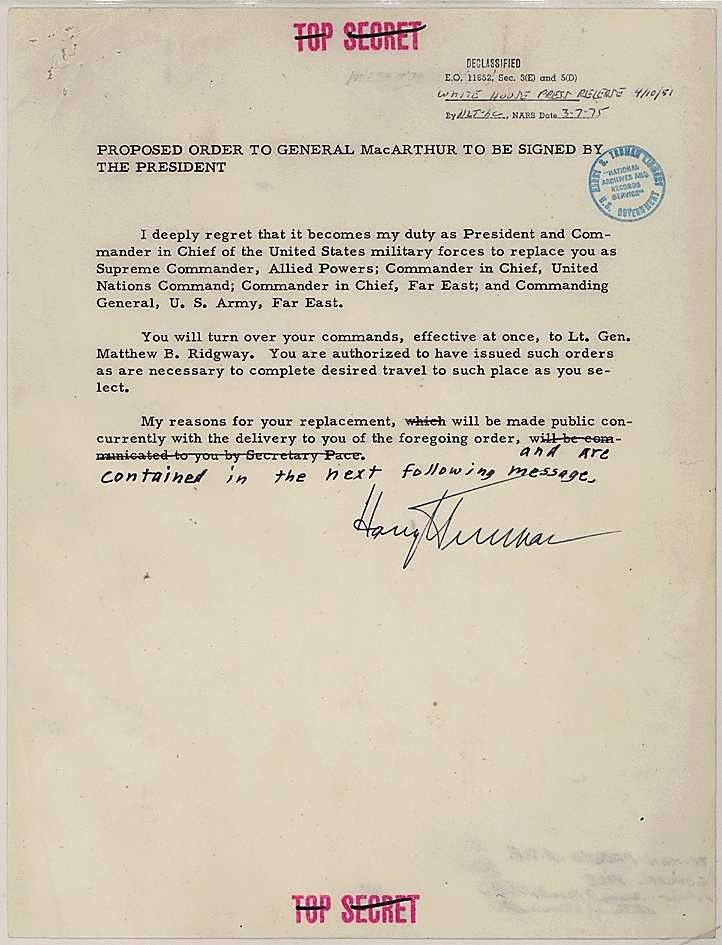

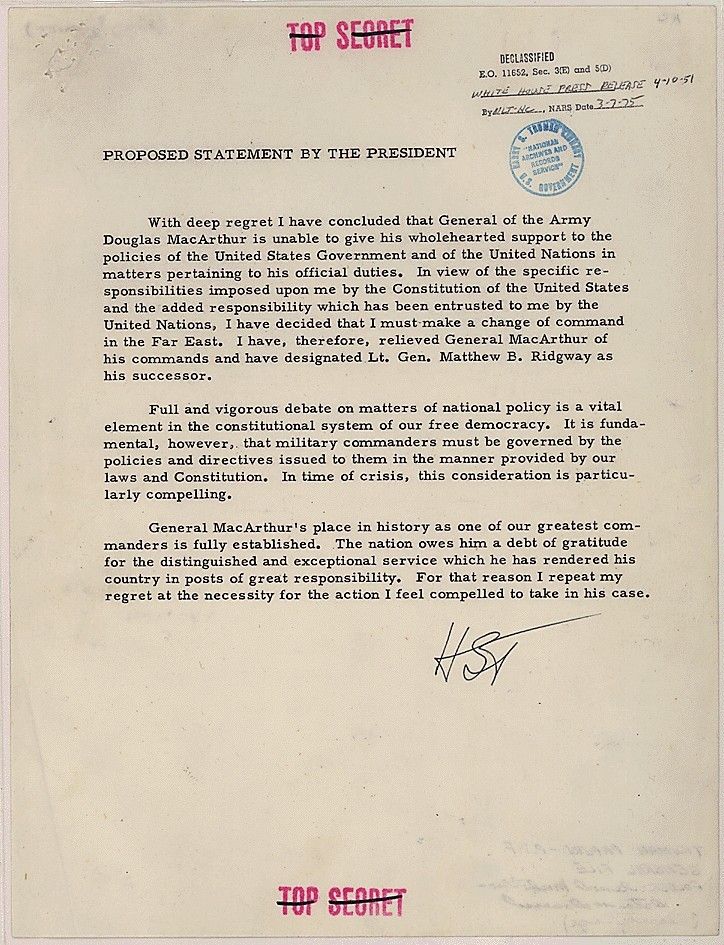

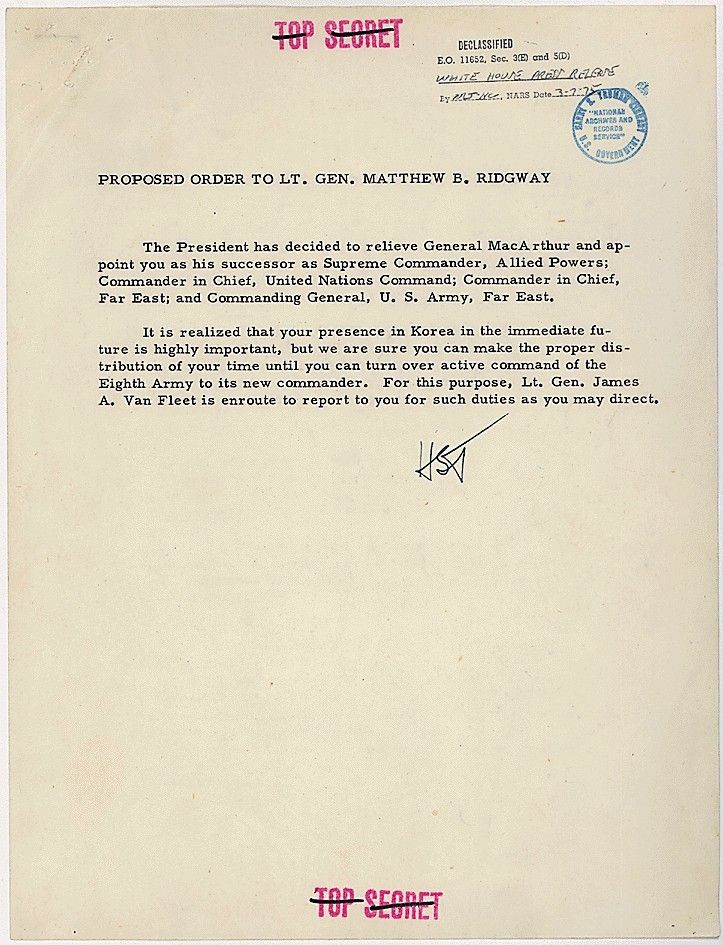

Proposed Orders and Statement on Dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur

Page 1

17

Activity Element

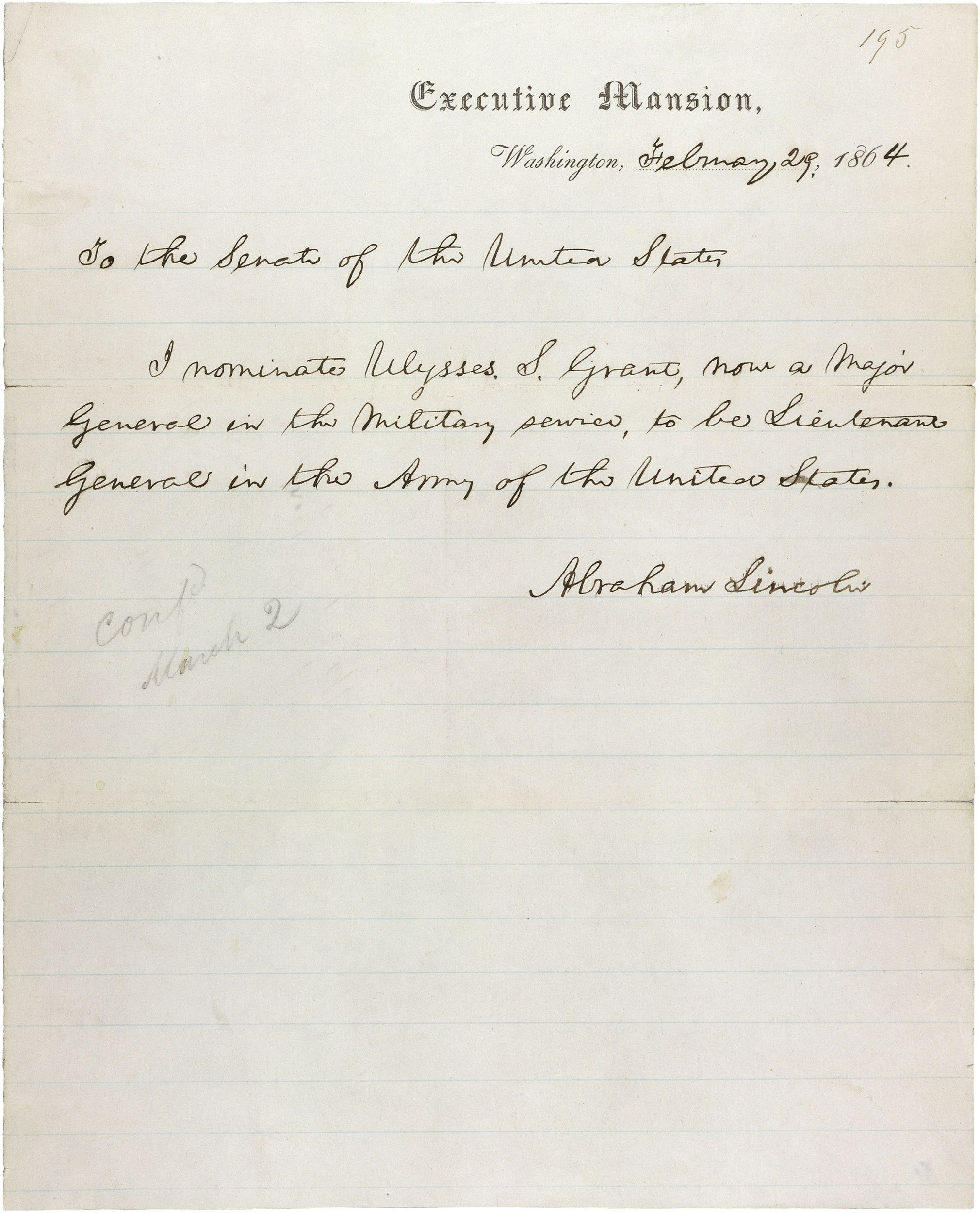

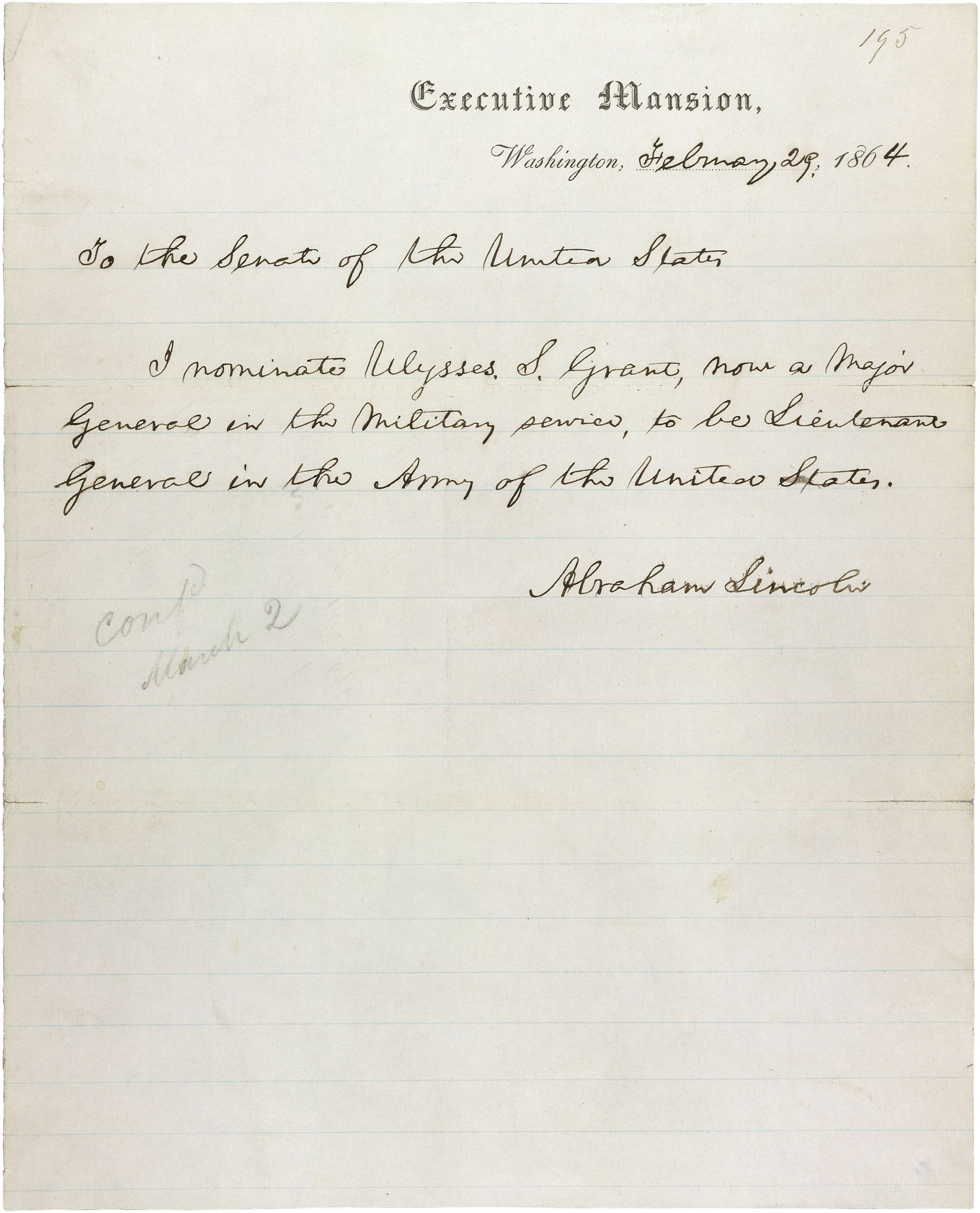

Message of President Abraham Lincoln Nominating Ulysses S. Grant to Be Lieutenant General of the Army

Page 2

18

Activity Element

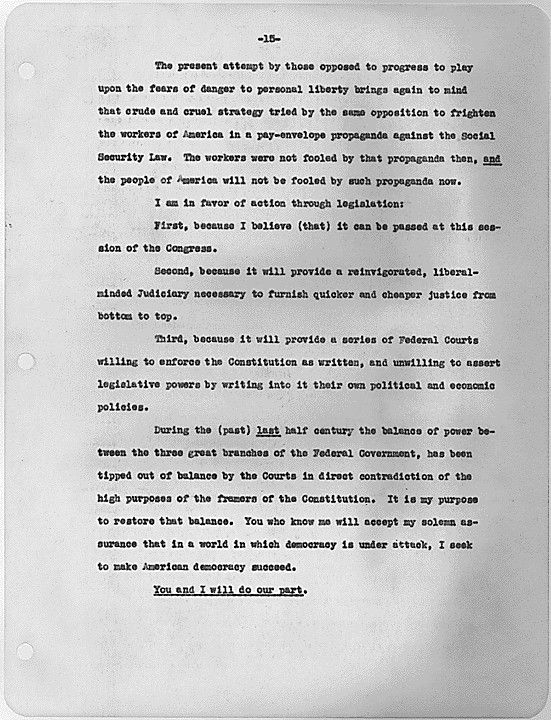

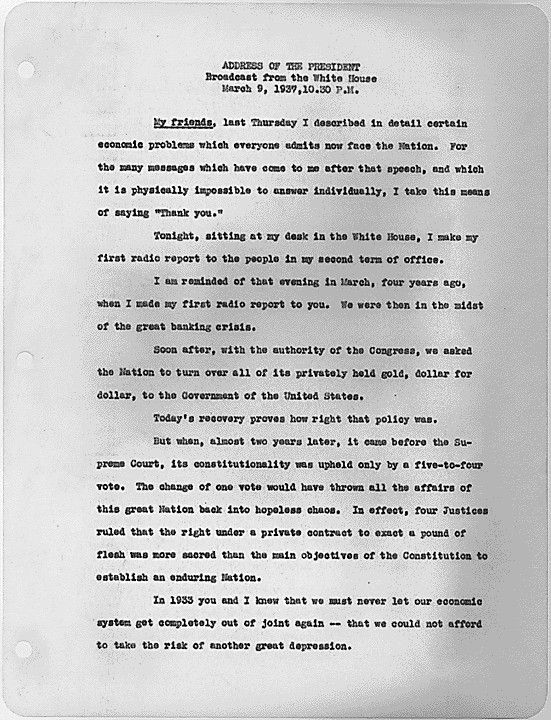

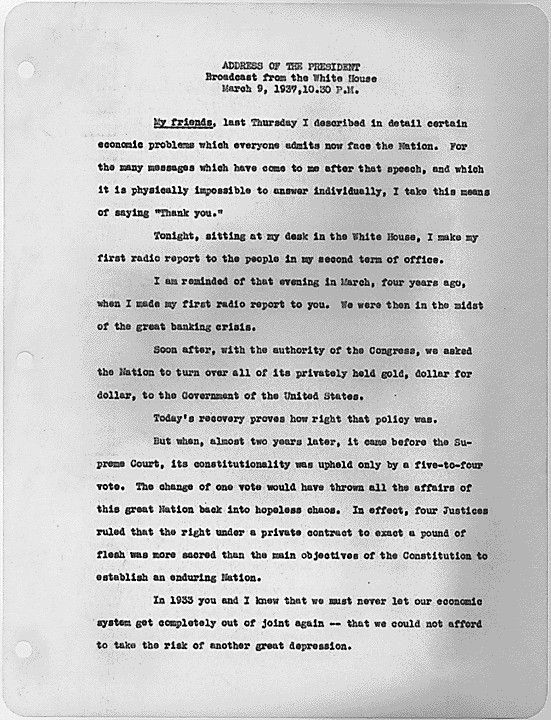

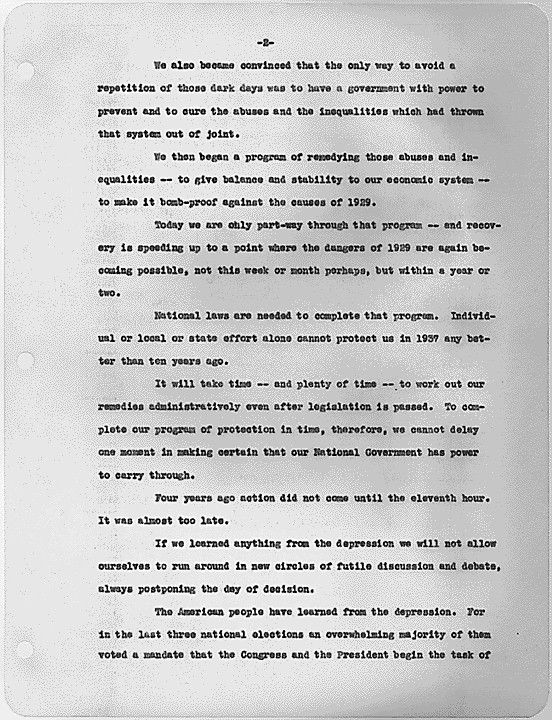

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 1

Conclusion

Separation of Powers or Shared Powers

Weighing the Evidence

Based on your analysis of the documents, does our government follow a "separation of powers" model or "shared powers" model? Cite specific evidence from the documents to explain your point of view.Your Response

Document

Senate Journal for the Second Session of the 77th Congress

7/16/1942

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 1148007

Full Citation: Senate Journal for the Second Session of the 77th Congress; 7/16/1942; Records of the U.S. Senate, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/senate-journal-for-the-second-session-of-the-77th-congress, April 20, 2024]Senate Journal for the Second Session of the 77th Congress

Page 1

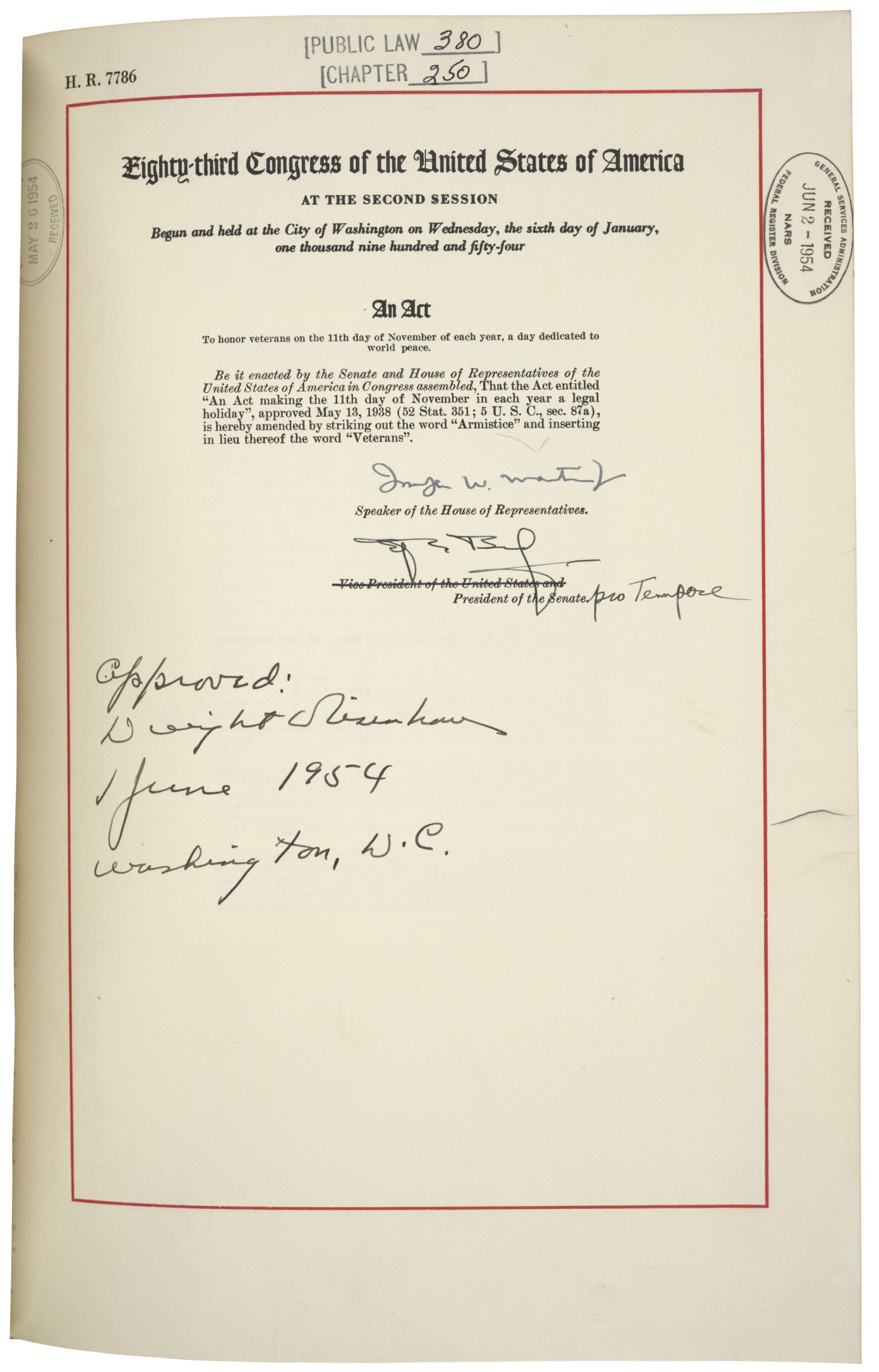

Document

[Bill to Honor Veterans] House Resolution 7786 of the 83rd Congress

3/16/1954

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 1157550

Full Citation: [Bill to Honor Veterans] House Resolution 7786 of the 83rd Congress; 3/16/1954; Records of the U.S. Senate, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/[bill-to-honor-veterans]-house-resolution-7786-of-the-83rd-congress, April 20, 2024][Bill to Honor Veterans] House Resolution 7786 of the 83rd Congress

Page 1

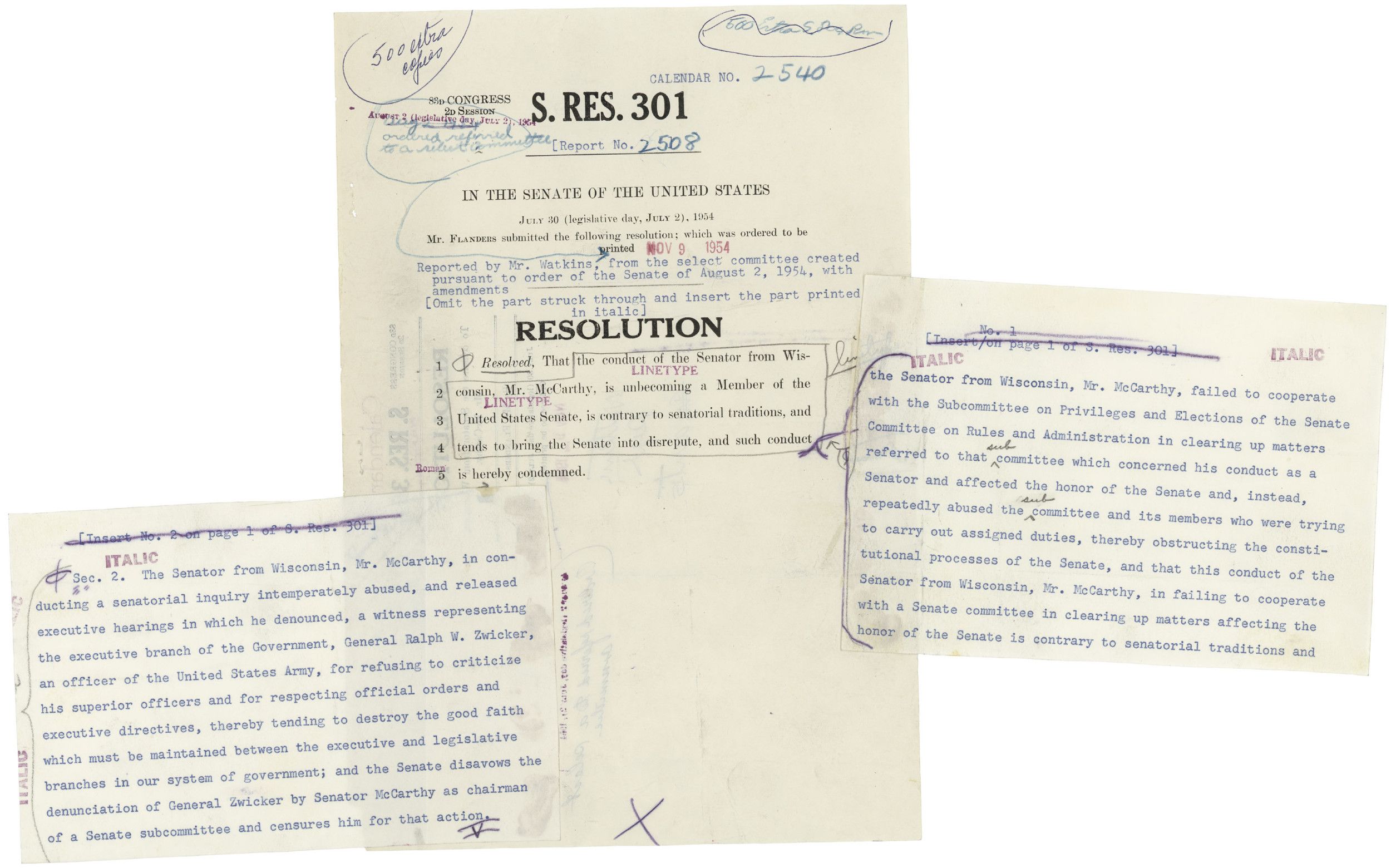

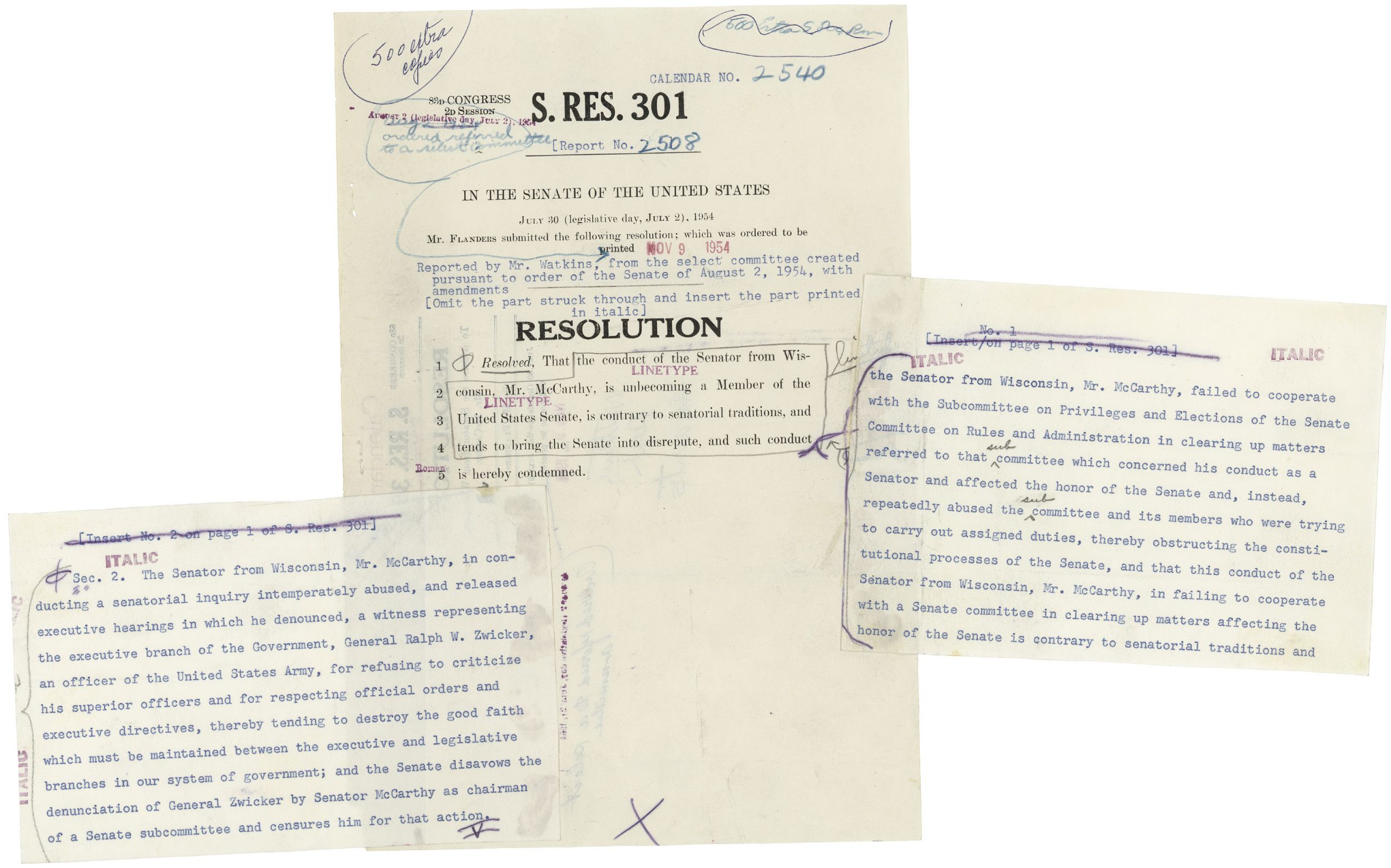

Document

Senate Resolution 301 of the 83rd Congress

7/30/1954

On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted to censure Senator Joseph McCarthy, who had led the fight in Congress to root out suspected Communists from the Federal Government. McCarthy had led televised investigations, forcing people to defend themselves in front of the American public. Some Members of Congress disagreed with McCarthy’s accusations and interrogation tactics and passed a resolution to censure him.

The early years of the Cold War saw the United States facing a hostile Soviet Union, the "loss" of China to communism, and war in Korea. In this politically charged atmosphere, fears of Communist influence over American institutions spread easily.

On February 9, 1950, Joseph McCarthy, a Republican Senator from Wisconsin, claimed that he had a list of 205 State Department employees who were Communists. While he offered little proof, the claims gained the Senator great notoriety.

In June, Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine and six fellow Republicans issued a "Declaration of Conscience" asserting that because of McCarthy’s tactics, the Senate had been "debased to the level of a forum for hate and character assassination." However, McCarthy took advantage of the Cold War atmosphere of fear and suspicion and with strong support in the opinion polls, McCarthy’s attacks and interventions in senatorial elections brought defeat to some of his party’s Democratic opponents.

After Republicans took control of the White House and Congress in 1953, McCarthy was named chairman of the Committee on Government Operations and its Subcommittee on Investigations. From these posts he continued to accuse Government agencies of being "soft" on communism, but he was now attacking a Republican administration.

In 1954 McCarthy’s investigation of security threats in the U.S. Army was televised. McCarthy’s bullying of witnesses turned public opinion against the Senator. On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted to censure him, describing his behavior as "contrary to senatorial traditions."

Republican Senators Ralph Flanders of Vermont, Arthur Watkins of Utah, and Margaret Chase Smith of Maine led the efforts to discipline McCarthy. Flanders introduced two separate resolutions against McCarthy, one removing McCarthy from his chairmanships and the other calling for his censure. The censure resolution moved forward with debate beginning July 30, 1954. The full Senate took up the resolution on November 5.

This copy of the resolution catches the debate on November 9 as the Senate refined the wording of its resolution. The substance of the first count, charging McCarthy with failure to cooperate with a Senate subcommittee, remained unchanged in the final resolution. The second count was dropped for a condemnation of McCarthy’s attacks on the very members of the committee that considered his censure.

The early years of the Cold War saw the United States facing a hostile Soviet Union, the "loss" of China to communism, and war in Korea. In this politically charged atmosphere, fears of Communist influence over American institutions spread easily.

On February 9, 1950, Joseph McCarthy, a Republican Senator from Wisconsin, claimed that he had a list of 205 State Department employees who were Communists. While he offered little proof, the claims gained the Senator great notoriety.

In June, Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine and six fellow Republicans issued a "Declaration of Conscience" asserting that because of McCarthy’s tactics, the Senate had been "debased to the level of a forum for hate and character assassination." However, McCarthy took advantage of the Cold War atmosphere of fear and suspicion and with strong support in the opinion polls, McCarthy’s attacks and interventions in senatorial elections brought defeat to some of his party’s Democratic opponents.

After Republicans took control of the White House and Congress in 1953, McCarthy was named chairman of the Committee on Government Operations and its Subcommittee on Investigations. From these posts he continued to accuse Government agencies of being "soft" on communism, but he was now attacking a Republican administration.

In 1954 McCarthy’s investigation of security threats in the U.S. Army was televised. McCarthy’s bullying of witnesses turned public opinion against the Senator. On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted to censure him, describing his behavior as "contrary to senatorial traditions."

Republican Senators Ralph Flanders of Vermont, Arthur Watkins of Utah, and Margaret Chase Smith of Maine led the efforts to discipline McCarthy. Flanders introduced two separate resolutions against McCarthy, one removing McCarthy from his chairmanships and the other calling for his censure. The censure resolution moved forward with debate beginning July 30, 1954. The full Senate took up the resolution on November 5.

This copy of the resolution catches the debate on November 9 as the Senate refined the wording of its resolution. The substance of the first count, charging McCarthy with failure to cooperate with a Senate subcommittee, remained unchanged in the final resolution. The second count was dropped for a condemnation of McCarthy’s attacks on the very members of the committee that considered his censure.

Transcript

Resolved, That the Senator from Wisconsin, Mr. McCarthy, failed to cooperate with the Subcommittee on Privileges and Elections of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration in clearing up matters referred to that subcommittee which concerned his conduct as a Senator and affected the honor of the Senate and, instead, repeatedly abused the subcommittee and its members who were trying to carry out assigned duties, thereby obstructing the constitutional processes of the Senate, and that this conduct of the Senator from Wisconsin, Mr. McCarthy, is contrary to senatorial traditions and is hereby condemned.Sec 2. The Senator from Wisconsin, Mr. McCarthy, in writing to the chairman of the Select Committee to Study Censure Charges (Mr. Watkins) after the Select Committee had issued its report and before the report was presented to the Senate charging three members of the Select Committee with "deliberate deception" and "fraud" for failure to disqualify themselves; in stating to the press on November 4, 1954, that the special Senate session that was to begin November 8, 1954, was a "lynch-party"; in repeatedly describing this special Senate session as a "lynch bee" in a nationwide television and radio show on November 7, 1954; in stating to the public press on November 13, 1954, that the chairman of the Select Committee (Mr. Watkins) was guilty of "the most unusual, most cowardly things I've ever heard of" and stating further: "I expected he would be afraid to answer the questions, but didn't think he'd be stupid enough to make a public statement"; and in characterizing the said committee as the "unwitting handmaiden," "involuntary agent" and "attorneys-in-fact" of the Communist Party and in charging that the said committee in writing its report "imitated Communist methods -- that it distorted, misrepresented, and omitted in its effort to manufacture a plausible rationalization" in support of its recommendations to the Senate, which characterizations and charges were contained in a statement released to the press and inserted in the Congressional Record of November 10, 1954, acted contrary to senatorial ethics and tended to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute, to obstruct the constitutional processes of the Senate, and to impair its dignity; and such conduct is hereby condemned.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 1157557

Full Citation: Senate Resolution 301 of the 83rd Congress; 7/30/1954; (SEN 83A-B4); Bills and Resolutions Originating in the Senate, 1789 - 2002; Records of the U.S. Senate, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/mccarthy-censure, April 20, 2024]Senate Resolution 301 of the 83rd Congress

Page 2

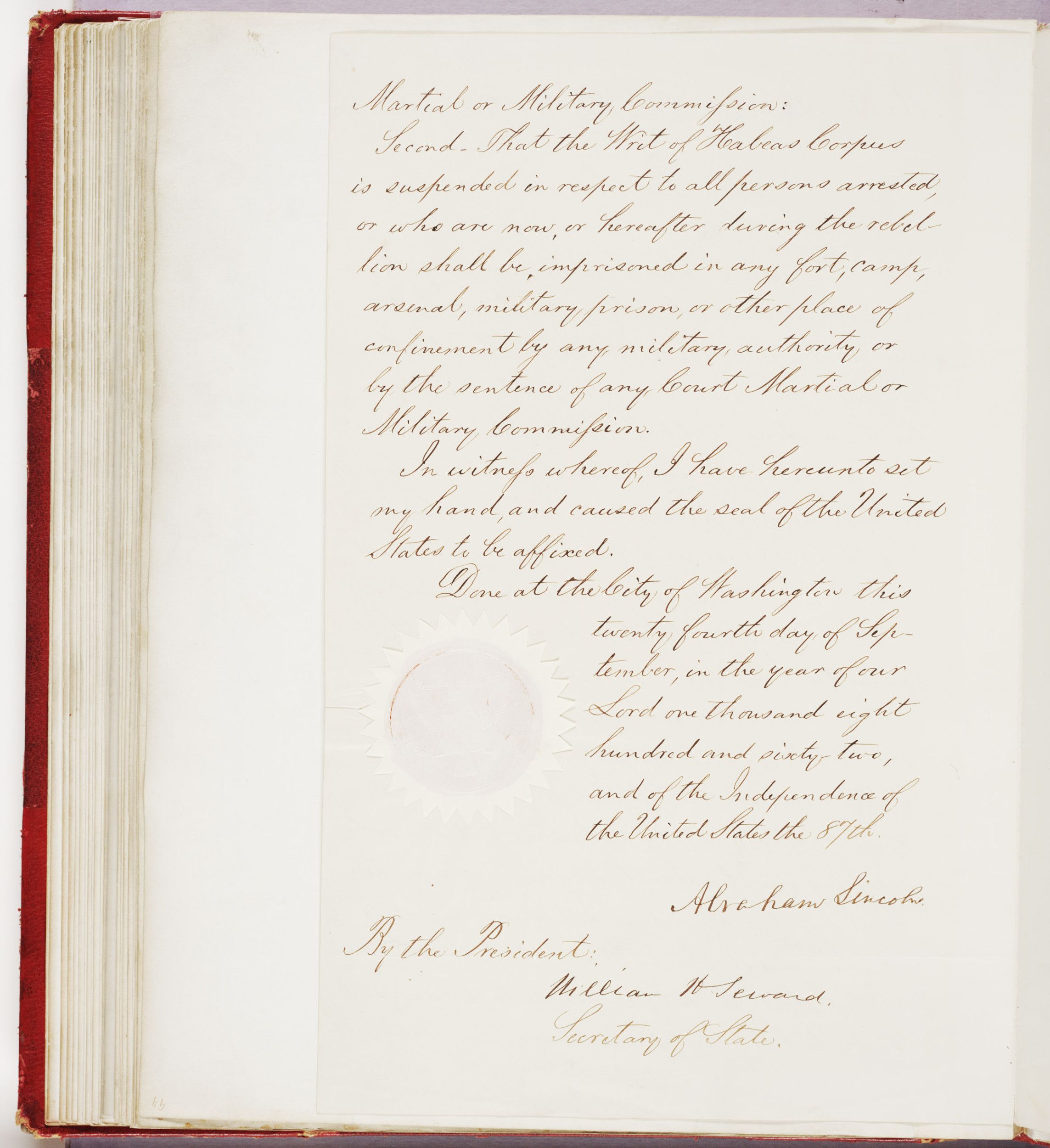

Document

Presidential Proclamation 94 of September 24, 1862, by President Abraham Lincoln suspending the writ of Habeas Corpus.

9/24/1862

President Abraham Lincoln issued this Presidential Proclamation 94 suspending the writ of habeas corpus during the Civil War. The writ of habeas corpus is a tool preventing the government from unlawfully imprisoning individuals outside of the judicial process.

Transcript

[page 1]By the President of the United States of America,

A Proclamation.

Whereas, it has become necessary to call into service not only volunteers but also portions of

the militia of the States by draft in order to suppress the insurrection existing in the United

States, and disloyal persons are not adequately restrained by the ordinary process of law from

hindering this measure and from giving aid and comfort in various ways to the insurrection;

Now, therefore, be it ordered, first, that during the existing insurrection and as a necessary

measure for suppressing the same, all Rebels and Insurgents, their aiders and abettors within the

United States, and all persons discouraging volunteer enlistments, resisting militia drafts, or

guilty of any disloyal practice, affording aid and comfort to Rebels against the authority of the

United States, shall be subject to martial law and liable to trial and punishment by Courts

[page 2]

Martial or Military Commission:

Second. That the Writ of Habeas Corpus is suspended in respect to all persons arrested, or who

are now, or hereafter during the rebellion shall be imprisoned in any fort, camp, arsenal, military

prison, or other place of confinement by any military authority or by the sentence of any Court

Martial or Military Commission.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be

affixed.

Done at the City of Washington this twenty fourth day of September, in the year of our Lord one

thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, and of the Independence of the United States the 87th .

[signed] Abraham Lincoln.

[signed] By the President:

William H Seward

Secretary of State.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 299959

Full Citation: Presidential Proclamation 94 of September 24, 1862, by President Abraham Lincoln suspending the writ of Habeas Corpus.; 9/24/1862; Presidential Proclamations, 1791 - 2016; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/lincoln-habeas-corpus, April 20, 2024]Presidential Proclamation 94 of September 24, 1862, by President Abraham Lincoln suspending the writ of Habeas Corpus.

Page 1

Presidential Proclamation 94 of September 24, 1862, by President Abraham Lincoln suspending the writ of Habeas Corpus.

Page 2

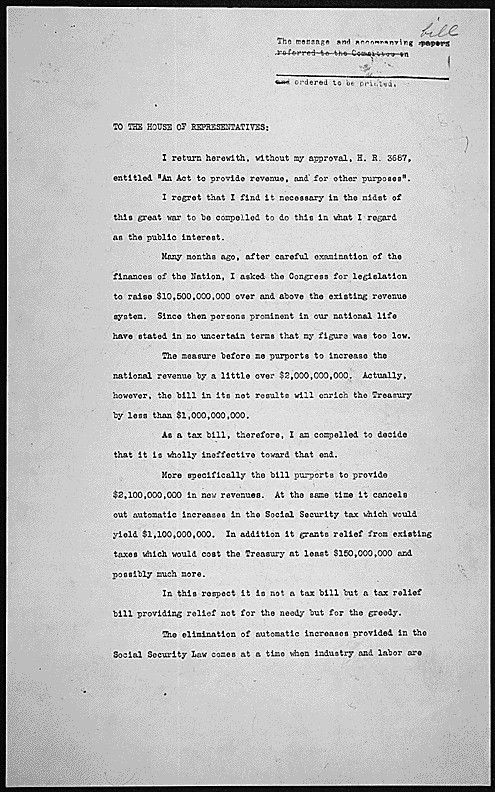

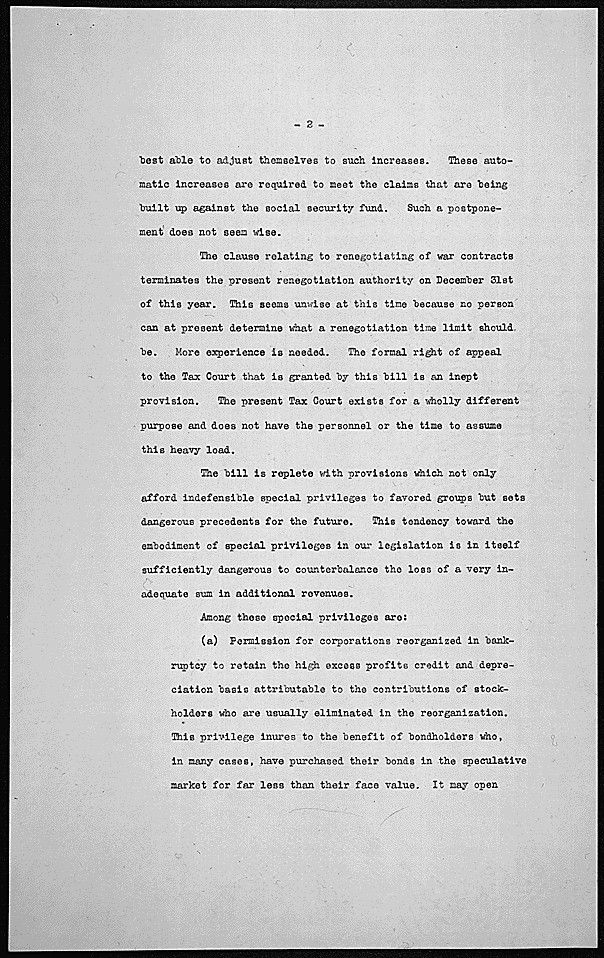

Document

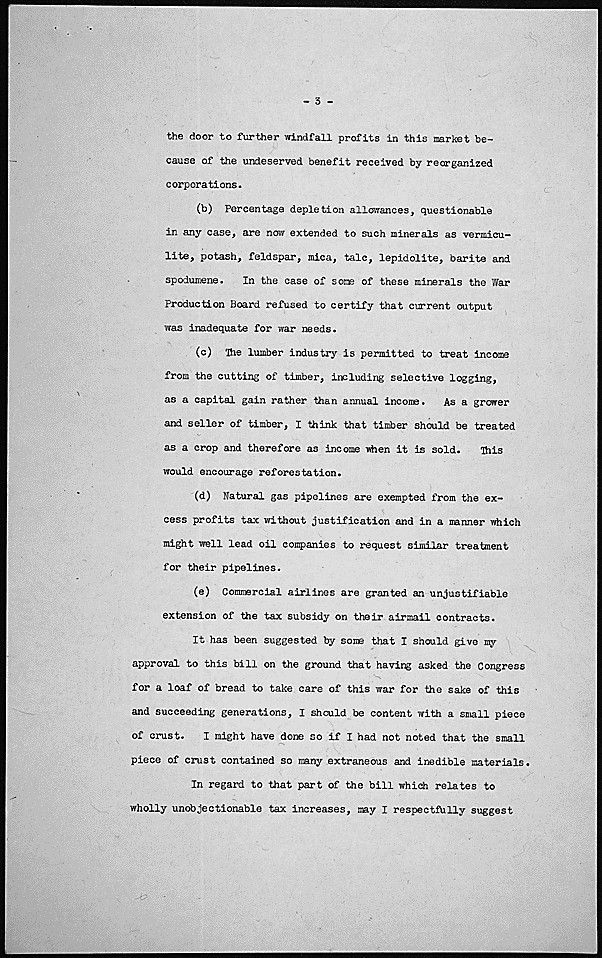

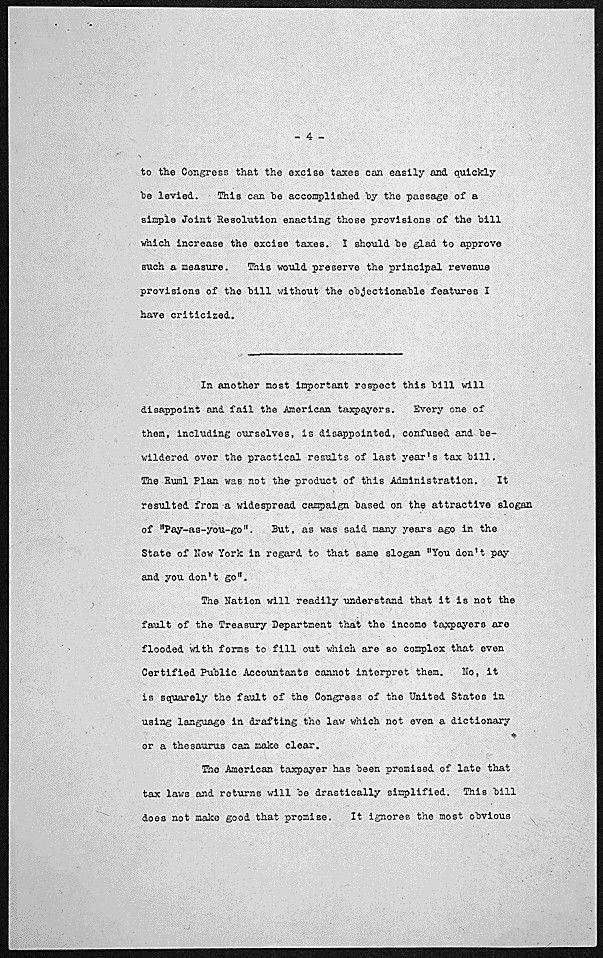

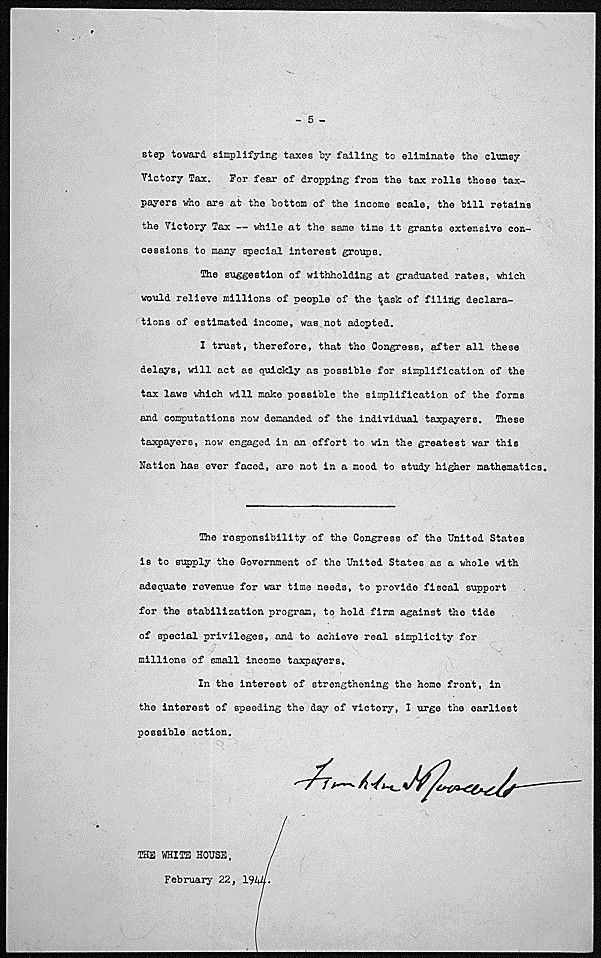

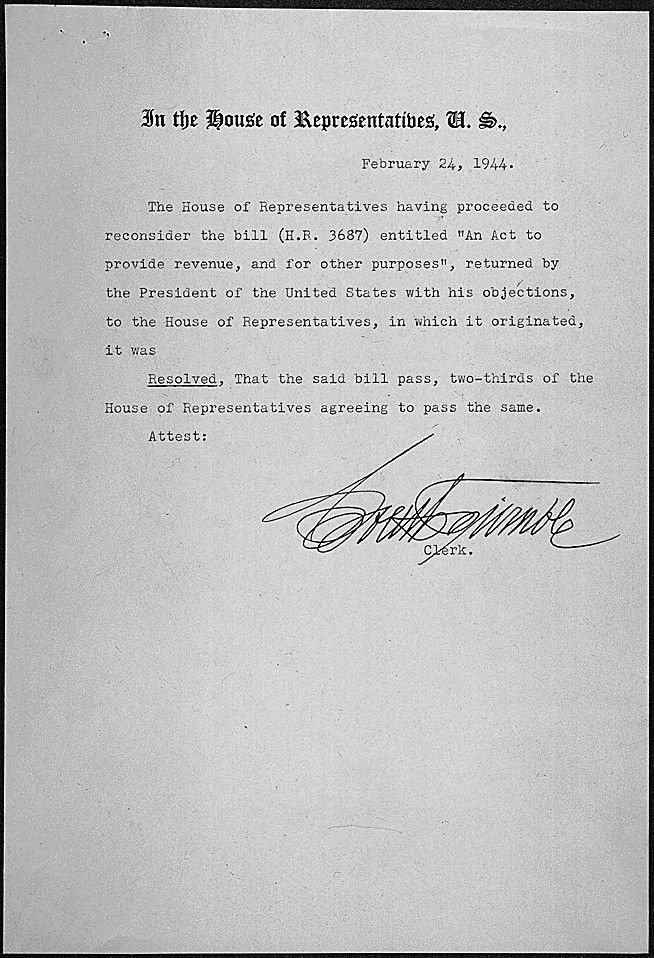

Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

02/22/1944

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 306452

Full Citation: Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives; 02/22/1944; Records of the U.S. Senate, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/veto-message-of-president-franklin-d-roosevelt-to-the-house-of-representatives, April 20, 2024]Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

Page 1

Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

Page 2

Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

Page 3

Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

Page 4

Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

Page 5

Veto message of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the House of Representatives

Page 6

Document

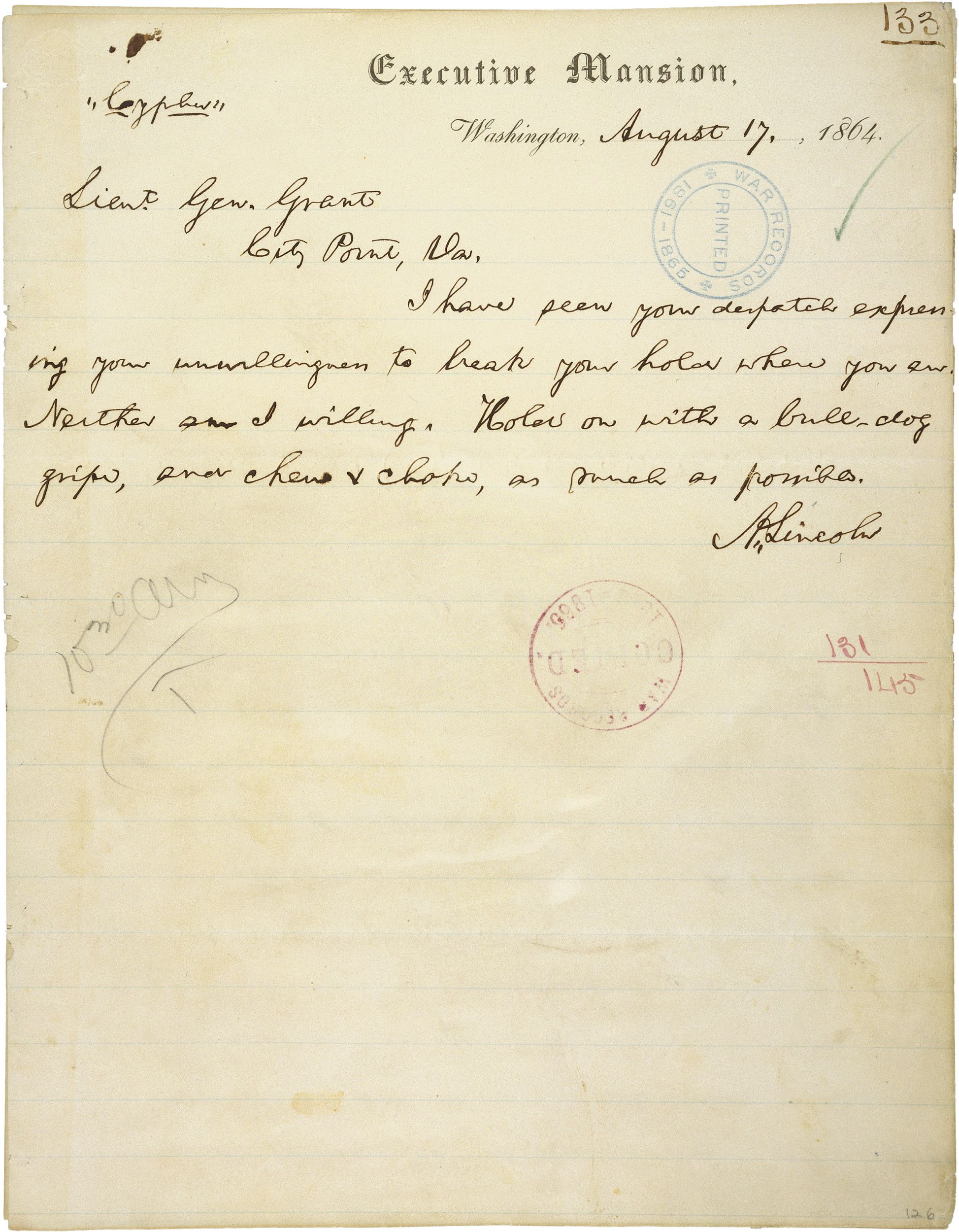

Telegram from Abraham Lincoln to Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant at City Point, Virginia

8/17/1864

Transcript

133“Cypher”

Executive mansion,

Washington, August 17. 1864.

Lieut. Gen. Grant

City Point VA.

[blue stamp] "PRINTED WAR RECORDS 1861-1865"

[handwritten check mark]

I have seen your dispatch expressing your unwillingness to break your hold where you are. Neither am I willing. Hold on with a bull-dog grip, and chew and choke, as much as possible.

[signed] A. Lincoln

1030 am / T [red stamp] “WAR RECORDS 1866” 131 / 145

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of the Secretary of War.

National Archives Identifier: 301640

Full Citation: Telegram from Abraham Lincoln to Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant at City Point, Virginia; 8/17/1864; Telegrams Sent and Received By The War Department Central Telegraph Office, 1861 - 1882; Records of the Office of the Secretary of War, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/lincoln-grant-city-point, April 20, 2024]Telegram from Abraham Lincoln to Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant at City Point, Virginia

Page 1

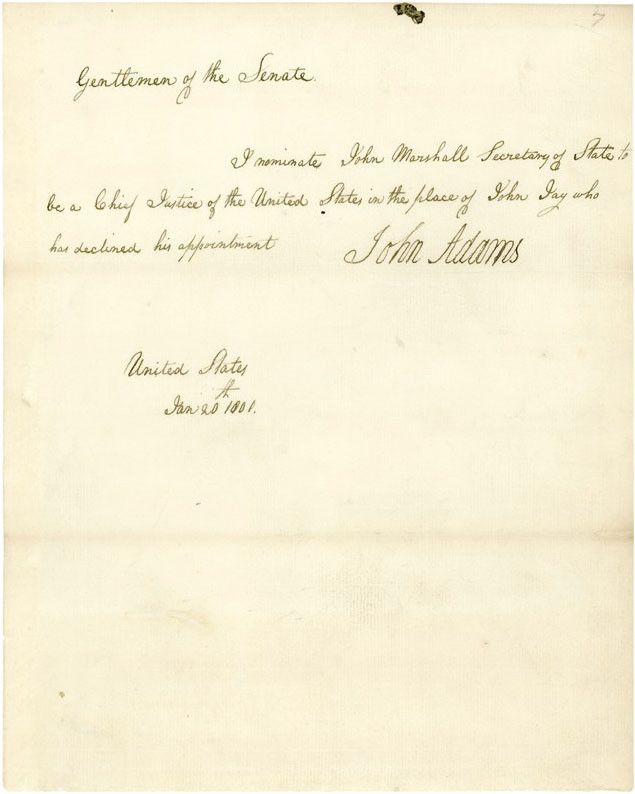

Document

Message of President John Adams nominating John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

1/20/1801

President John Adams sent this message nominating John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Transcript

Gentlemen of the SenateI nominate John Marshall Secretary of State to be Chief Justice of the United States in the place of John Jay who has declined his appointment

John Adams

United States

Jan 20 1801

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 306290

Full Citation: Message of President John Adams nominating John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; 1/20/1801; Anson McCook Collection of Presidential Signatures, 1789 - 1975; Records of the U.S. Senate, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/marshall-nomination, April 20, 2024]Message of President John Adams nominating John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

Page 1

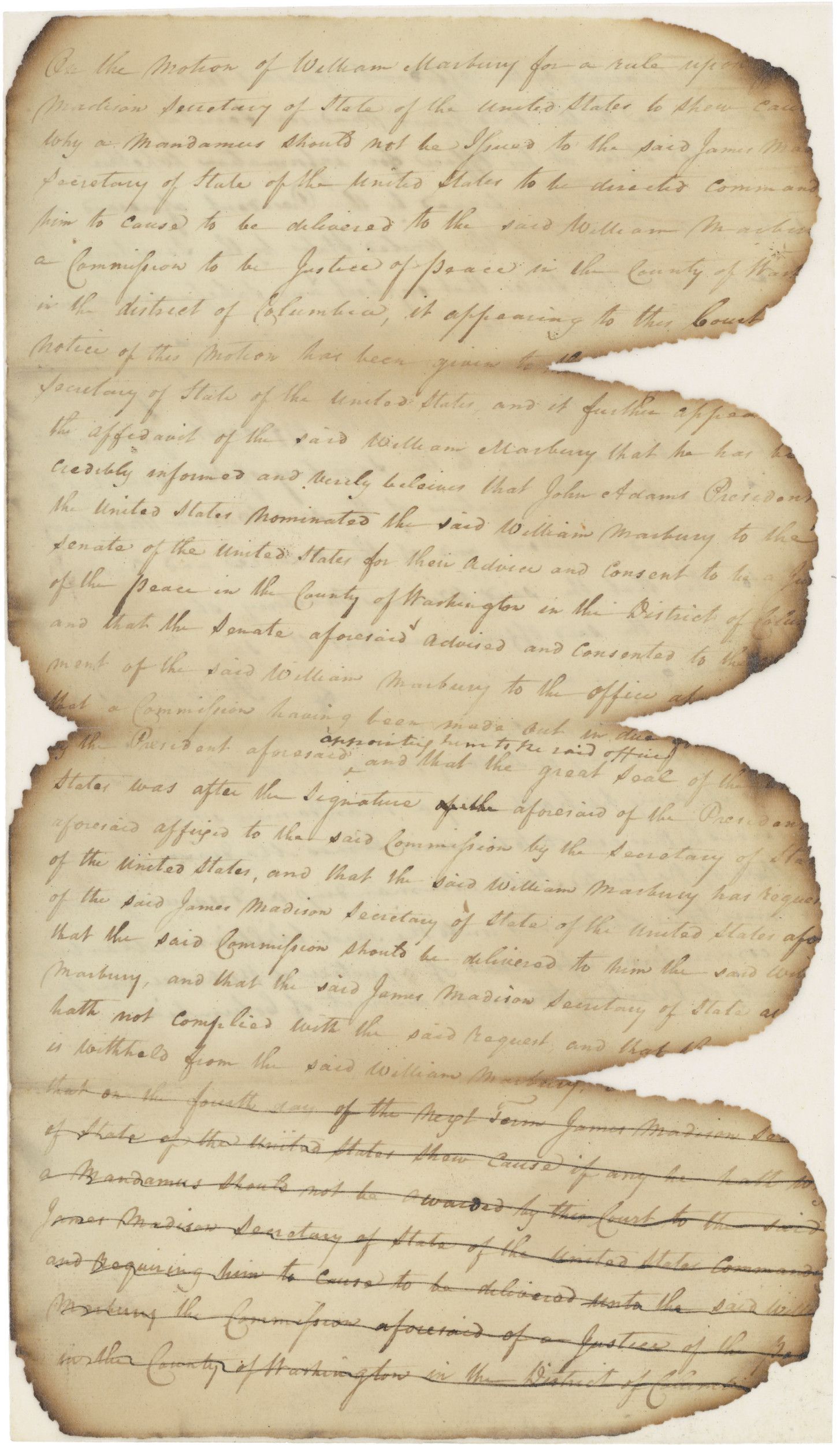

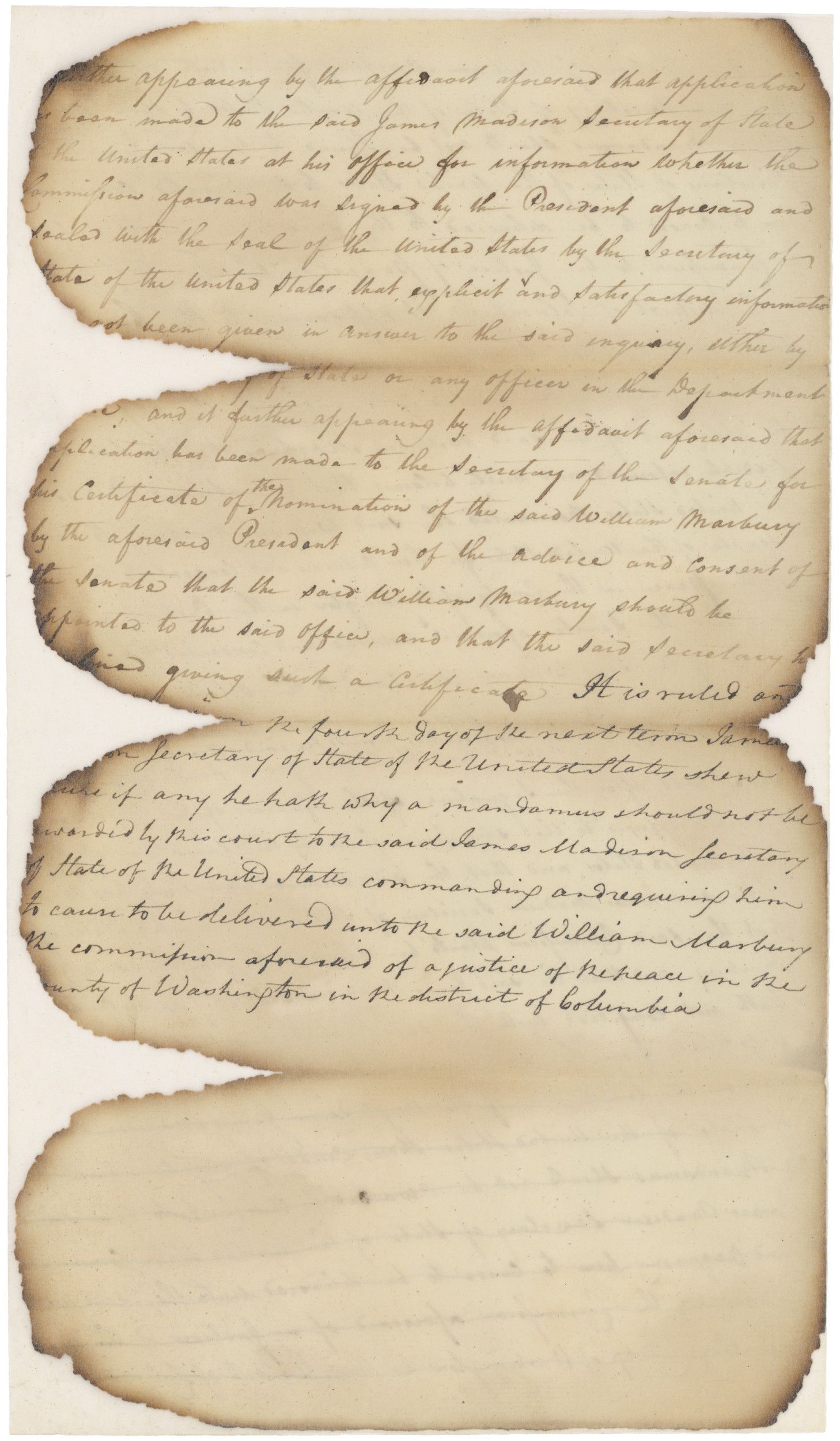

Document

Draft of Motion Rule for Marbury v. Madison

1803

Marbury v. Madison established the idea of judicial review, the ability of the Supreme Court to determine the constitutionality of the actions of the other two branches of government — an important addition to the system of “checks and balances” created to prevent any one branch of the Federal Government from becoming too powerful. The Supreme Court is the final authority on the meaning of the Constitution. Overturning its decisions often requires an amendment to the Constitution or a revision of Federal law.

In March 1801, in the final days of his administration, President John Adams appointed William Marbury as Justice of the Peace in the District of Columbia. Incoming Secretary of State, James Madison (under new President Thomas Jefferson), refused to deliver Marbury’s commission. Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court for a "writ of mandamus" (a command to a lower court or person to perform a public duty) requiring Madison to show cause as to why he should not receive his commission.

The Supreme Court ruled that it could not issue the mandamus. It decided that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which would have given the Court the ability to do so, was unconstitutional. Chief Justice John Marshall said “A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.”

With these words, the Supreme Court for the first time declared unconstitutional a law passed by Congress and signed by the President. Nothing in the Constitution gave the Court this specific power. Marshall, however, believed that the Supreme Court should have a role equal to those of the other two branches of government.

The writers of the Constitution had given the executive and legislative branches powers that would limit each other as well as the judiciary branch. The Constitution gave Congress the power to impeach and remove officials, including judges or the President himself. The President was given the veto power to restrain Congress and the authority to appoint members of the Supreme Court with the advice and consent of the Senate. In this intricate system, the role of the Supreme Court had not been defined. It therefore fell to a strong Chief Justice like Marshall to complete the triangular structure of checks and balances by establishing the principle of judicial review.

Although no other law was declared unconstitutional until the Dred Scott decision of 1857, the role of the Supreme Court to invalidate Federal and state laws that are contrary to the Constitution has never been seriously challenged.

This document shows damage from the 1898 fire in the Capitol Building.

In March 1801, in the final days of his administration, President John Adams appointed William Marbury as Justice of the Peace in the District of Columbia. Incoming Secretary of State, James Madison (under new President Thomas Jefferson), refused to deliver Marbury’s commission. Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court for a "writ of mandamus" (a command to a lower court or person to perform a public duty) requiring Madison to show cause as to why he should not receive his commission.

The Supreme Court ruled that it could not issue the mandamus. It decided that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which would have given the Court the ability to do so, was unconstitutional. Chief Justice John Marshall said “A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.”

With these words, the Supreme Court for the first time declared unconstitutional a law passed by Congress and signed by the President. Nothing in the Constitution gave the Court this specific power. Marshall, however, believed that the Supreme Court should have a role equal to those of the other two branches of government.

The writers of the Constitution had given the executive and legislative branches powers that would limit each other as well as the judiciary branch. The Constitution gave Congress the power to impeach and remove officials, including judges or the President himself. The President was given the veto power to restrain Congress and the authority to appoint members of the Supreme Court with the advice and consent of the Senate. In this intricate system, the role of the Supreme Court had not been defined. It therefore fell to a strong Chief Justice like Marshall to complete the triangular structure of checks and balances by establishing the principle of judicial review.

Although no other law was declared unconstitutional until the Dred Scott decision of 1857, the role of the Supreme Court to invalidate Federal and state laws that are contrary to the Constitution has never been seriously challenged.

This document shows damage from the 1898 fire in the Capitol Building.

Transcript

Chief Justice Marshall delivered the opinion of the Court.At the last term on the affidavits then read and filed with the clerk, a rule was granted in this case, requiring the Secretary of State to show cause why a mandamus should not issue, directing him to deliver to William Marbury his commission as a justice of the peace for the county of Washington, in the district of Columbia.

No cause has been shown, and the present motion is for a mandamus. The peculiar delicacy of this case, the novelty of some of its circumstances, and the real difficulty attending the points which occur in it, require a complete exposition of the principles on which the opinion to be given by the court is founded. . . .

In the order in which the court has viewed this subject, the following questions have been considered and decided:

1st. Has the applicant a right to the commission he demands?

2d. If he has a right, and that right has been violated, do the laws of his country afford him a remedy?

3d. If they do afford him a remedy, is it a mandamus issuing from this court?

The first object of inquiry is -- 1st. Has the applicant a right to the commission he demands? . . .

It [is] decidedly the opinion of the court, that when a commission has been signed by the president, the appointment is made; and that the commission is complete, when the seal of the United States has been affixed to it by the secretary of state. . . .

To withhold his commission, therefore, is an act deemed by the court not warranted by law, but violative of a vested legal right.

This brings us to the second inquiry; which is 2dly. If he has a right, and that right has been violated, do the laws of his country afford him a remedy?

The very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws, whenever he receives an injury. One of the first duties of government is to afford that protection. [The] government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men. It will certainly cease to deserve this high appellation, if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right. . . .

By the constitution of the United States, the President is invested with certain important political powers, in the exercise of which he is to use his own discretion, and is accountable only to his country in his political character, and to his own conscience. To aid him in the performance of these duties, he is authorized to appoint certain officers, who act by his authority and in conformity with his orders.

In such cases, their acts are his acts; and whatever opinion may be entertained of the manner in which executive discretion may be used, still there exists, and can exist, no power to control that discretion. The subjects are political. They respect the nation, not individual rights, and being entrusted to the executive, the decision of the executive is conclusive. . . .

But when the legislature proceeds to impose on that officer other duties; when he is directed peremptorily to perform certain acts; when the rights of individuals are dependent on the performance of those acts; he is so far the officer of the law; is amenable to the laws for his conduct; and cannot at his discretion sport away the vested rights of others.

The conclusion from this reasoning is, that where the heads of departments are the political or confidential agents of the executive, merely to execute the will of the President, or rather to act in cases in which the executive possesses a constitutional or legal discretion, nothing can be more perfectly clear than that their acts are only politically examinable. But where a specific duty is assigned by law, and individual rights depend upon the performance of that duty, it seems equally clear, that the individual who considers himself injured, has a right to resort to the laws of his country for a remedy. . . .

It is, then, the opinion of the Court [that Marbury has a] right to the commission; a refusal to deliver which is a plain violation of that right, for which the laws of his country afford him a remedy.

It remains to be enquired whether,

3dly. He is entitled to the remedy for which he applies. This depends on -- 1st. The nature of the writ applied for, and,

2dly. The power of this court.

1st. The nature of the writ. . . .

This, then, is a plain case for a mandamus, either to deliver the commission, or a copy of it from the record; and it only remains to be enquired,

Whether it can issue from this court.

The act to establish the judicial courts of the United States authorizes the Supreme Court "to issue writs of mandamus in cases warranted by the principles and usages of law, to any courts appointed, or persons holding office, under the authority of the United States."

The Secretary of State, being a person holding an office under the authority of the United States, is precisely within the letter of the description; and if this court is not authorized to issue a writ of mandamus to such an officer, it must be because the law is unconstitutional, and therefore incapable of conferring the authority, and assigning the duties which its words purport to confer and assign.

The constitution vests the whole judicial power of the United States in one Supreme Court, and such inferior courts as congress shall, from time to time, ordain and establish. This power is expressly extended to all cases arising under the laws of the United States; and, consequently, in some form, may be exercised over the present case; because the right claimed is given by a law of the United States.

In the distribution of this power it is declared that "the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction in all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be a party. In all other cases, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction."

It has been insisted, at the bar, that as the original grant of jurisdiction, to the supreme and inferior courts, is general, and the clause, assigning original jurisdiction to the Supreme Court, contains no negative or restrictive words, the power remains to the legislature, to assign original jurisdiction to that court in other cases than those specified in the article which has been recited; provided those cases belong to the judicial power of the United States.

If it had been intended to leave it in the discretion of the legislature to apportion the judicial power between the supreme and inferior courts according to the will of that body, it would certainly have been useless to have proceeded further than to have defined the judicial power, and the tribunals in which it should be vested. The subsequent part of the section is mere surplusage, is entirely without meaning, if such is to be the construction. If congress remains at liberty to give this court appellate jurisdiction, where the constitution has declared their jurisdiction shall be original; and original jurisdiction where the constitution has declared it shall be appellate; the distribution of jurisdiction, made in the constitution, is form without substance.

Affirmative words are often, in their operation, negative of other objects than those affirmed; and in this case, a negative or exclusive sense must be given to them or they have no operation at all.

It cannot be presumed that any clause in the constitution is intended to be without effect; and, therefore, such a construction is inadmissible, unless the words require it.

If the solicitude of the convention, respecting our peace with foreign powers, induced a provision that the supreme court should take original jurisdiction in cases which might be supposed to affect them; yet the clause would have proceeded no further than to provide for such cases, if no further restriction on the powers of congress had been intended. That they should have appellate jurisdiction in all other cases, with such exceptions as congress might make, is no restriction; unless the words be deemed exclusive of original jurisdiction.

When an instrument organizing fundamentally a judicial system, divides it into one supreme, and so many inferior courts as the legislature may ordain and establish; then enumerates its powers, and proceeds so far to distribute them, as to define the jurisdiction of the supreme court by declaring the cases in which it shall take original jurisdiction, and that in others it shall take appellate jurisdiction; the plain import of the words seems to be, that in one class of cases its jurisdiction is original, and not appellate; in the other it is appellate, and not original. If any other construction would render the clause inoperative, that is an additional reason for rejecting such other construction, and for adhering to their obvious meaning.

To enable this court, then, to issue a mandamus, it must be shown to be an exercise of appellate jurisdiction, or to be necessary to enable them to exercise appellate jurisdiction.

It has been stated at the bar that the appellate jurisdiction may be exercised in a variety of forms, and that if it be the will of the legislature that a mandamus should be used for that purpose, that will must be obeyed. This is true, yet the jurisdiction must be appellate, not original.

It is the essential criterion of appellate jurisdiction, that it revises and corrects the proceedings in a cause already instituted, and does not create that cause. Although, therefore, a mandamus may be directed to courts, yet to issue such a writ to an officer for the delivery of a paper, is in effect the same as to sustain an original action for that paper, and, therefore, seems not to belong to appellate, but to original jurisdiction. Neither is it necessary in such a case as this, to enable the court to exercise its appellate jurisdiction.

The authority, therefore, given to the Supreme Court, by the act establishing the judicial courts of the United States, to issue writs of mandamus to public officers, appears not to be warranted by the constitution; and it becomes necessary to enquire whether a jurisdiction, so conferred, can be exercised.

The question, whether an act, repugnant to the constitution, can become the law of the land, is a question deeply interesting to the United States; but happily, not of an intricacy proportioned to its interest. It seems only necessary to recognize certain principles, supposed to have been long and well established, to decide it.

That the people have an original right to establish, for their future govern-ment, such principles as, in their opinion, shall most conduce to their own happiness, is the basis on which the whole American fabric has been erected. The exercise of this original right is a very great exertion; nor can it, nor ought it, to be frequently repeated. The principles, therefore, so established, are deemed fundamental. And as the authority from which they proceed is supreme, and can seldom act, they are designed to be permanent.

This original and supreme will organizes the government, and assigns to different departments their respective powers. It may either stop here, or establish certain limits not to be transcended by those departments.

The government of the United States is of the latter description. The powers of the legislature are defined and limited; and that those limits may not be mistaken, or forgotten, the constitution is written. To what purpose are powers limited, and to what purpose is that limitation committed to writing, if these limits may, at any time, be passed by those intended to be restrained? The distinction between a government with limited and unlimited powers is abolished, if those limits do not confine the persons on whom they are imposed, and if acts prohibited and acts allowed, are of equal obligation. It is a proposition too plain to be contested, that the constitution controls any legislative act repugnant to it; or, that the legislature may alter the constitution by an ordinary act.

Between these alternatives there is no middle ground. The constitution is either a superior, paramount law, unchangeable by ordinary means, or it is on a level with ordinary legislative acts, and, like other acts, is alterable when the legislature shall please to alter it.

If the former part of the alternative be true, then a legislative act contrary to the constitution is not law: if the latter part be true, then written constitutions are absurd attempts, on the part of the people, to limit a power in its own nature illimitable.

Certainly all those who have framed written constitutions contemplate them as forming the fundamental and paramount law of the nation, and consequently, the theory of every such government must be, that an act of the legislature, repugnant to the constitution, is void.

This theory is essentially attached to a written constitution, and is, conse-quently, to be considered, by this court, as one of the fundamental principles of our society. It is not therefore to be lost sight of in the further consideration of this subject.

If an act of the legislature, repugnant to the constitution, is void, does it, notwithstanding its invalidity, bind the courts, and oblige them to give it effect? Or, in other words, though it be not law, does it constitute a rule as operative as if it was a law? This would be to overthrow in fact what was established in theory; and would seem, at first view, an absurdity too gross to be insisted on. It shall, however, receive a more attentive consideration.

It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each.

So if a law be in opposition to the constitution; if both the law and the constitution apply to a particular case, so that the court must either decide that case conformably to the law, disregarding the constitution; or conformably to the constitution, disregarding the law; the court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case. This is of the very essence of judicial duty.

If, then, the courts are to regard the constitution, and the constitution is superior to any ordinary act of the legislature, the constitution, and not such ordinary act, must govern the case to which they both apply.

Those then who controvert the principle that the constitution is to be considered, in court, as a paramount law, are reduced to the necessity of maintaining that the courts must close their eyes on the constitution, and see only the law.

This doctrine would subvert the very foundation of all written constitutions. It would declare that an act which, according to the principles and theory of our government, is entirely void, is yet, in practice, completely obligatory. It would declare that if the legislature shall do what is expressly forbidden, such act, notwithstanding the express prohibition, is in reality effectual. It would be giving to the legislature a practical and real omnipotence, with the same breath which professes to restrict their powers within narrow limits. It is prescribing limits, and declaring that those limits may be passed at pleasure.

That it thus reduces to nothing what we have deemed the greatest improvement on political institutions -- a written constitution -- would of itself be sufficient, in America, where written constitutions have been viewed with so much reverence, for rejecting the construction. But the peculiar expressions of the constitution of the United States furnish additional arguments in favour of its rejection.

The judicial power of the United States is extended to all cases arising under the constitution.

Could it be the intention of those who gave this power, to say that in using it the constitution should not be looked into? That a case arising under the constitution should be decided without examining the instrument under which it arises?

This is too extravagant to be maintained.

In some cases, then, the constitution must be looked into by the judges. And if they can open it at all, what part of it are they forbidden to read or to oey?

There are many other parts of the constitution which serve to illustrate this subject.

It is declared that "no tax or duty shall be laid on articles exported from any state." Suppose a duty on the export of cotton, of tobacco, or of flour; and a suit instituted to recover it. Ought judgment to be rendered in such a case? Ought the judges to close their eyes on the constitution, and only see the law?

The constitution declares that "no bill of attainder or ex post facto law shall be passed." If, however, such a bill should be passed, and a person should be prosecuted under it; must the court condemn to death those victims whom the constitution endeavors to preserve?

"No person," says the constitution, "shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court."

Here the language of the constitution is addressed especially to the courts. It prescribes, directly for them, a rule of evidence not to be departed from. If the legislature should change that rule, and declare one witness, or a confession out of court, sufficient for conviction, must the constitutional principle yield to the legislative act?

From these, and many other selections which might be made, it is apparent, that the framers of the constitution contemplated that instrument as a rule for the government of courts, as well as of the legislature. Why otherwise does it direct the judges to take an oath to support it? This oath certainly applies, in an especial manner, to their conduct in their official character. How immoral to impose it on them, if they were to be used as the instruments, and the knowing instruments, for violating what they swear to support!

The oath of office, too, imposed by the legislature, is completely demonstrative of the legislative opinion on this subject. It is in these words: "I do solemnly swear that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich; and that I will faithfully and impartially discharge all the duties incumbent on me as _____, according to the best of my abilities and understanding, agreeably to the constitution, and laws of the United States." Why does a Judge swear to discharge his duties agreeably the constitution of the United States, if that constitution forms no rule for his government? If it is closed upon him, and cannot be inspected by him?

If such be the real state of things, this is worse than solemn mockery. To prescribe, or to take this oath, becomes equally a crime.

It is also not entirely unworthy of observation that in declaring what shall be the supreme law of the land, the constitution itself is first mentioned; and not the laws of the United States generally, but those only which shall be made in pursuance of the constitution, have that rank.

Thus, the particular phraseology of the constitution of the United States confirms and strengthens the principle, supposed to be essential to all written constitutions, that a law repugnant to the constitution is void; and that courts, as well as other departments, are bound by that instrument.

The rule must be discharged.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Supreme Court of the United States.

National Archives Identifier: 1497352

Full Citation: Draft of Motion Rule for Marbury v. Madison; 1803; Original Jurisdiction Case Files, 1792 - 1998; Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/draft-marbury-madison, April 20, 2024]Draft of Motion Rule for Marbury v. Madison

Page 1

Draft of Motion Rule for Marbury v. Madison

Page 2

Document

Presidential Proclamation 4311 of September 8, 1974, by President Gerald R. Ford granting a pardon to Richard M. Nixon.

9/8/1974

Gerald Ford was Vice President under President Richard Nixon and took over the Presidency when Nixon resigned. Nixon was under investigation for criminal activity while in office. With this document, Ford pardoned Nixon of any crimes he might have committed while President.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 299996

Full Citation: Presidential Proclamation 4311 of September 8, 1974, by President Gerald R. Ford granting a pardon to Richard M. Nixon.; 9/8/1974; General Records of the United States Government, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/presidential-proclamation-4311-of-september-8-1974-by-president-gerald-r-ford-granting-a-pardon-to-richard-m-nixon, April 20, 2024]Presidential Proclamation 4311 of September 8, 1974, by President Gerald R. Ford granting a pardon to Richard M. Nixon.

Page 2

Presidential Proclamation 4311 of September 8, 1974, by President Gerald R. Ford granting a pardon to Richard M. Nixon.

Page 2

Document

Judgment, Brown v. Board of Education

5/31/1955

On May 17, 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (five separate cases consolidated under a single name), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that separate but equal public schools violated the 14th Amendment.

On May 31, 1955 – one year and two weeks after the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional – Chief Justice Earl Warren issued this decree, ruling how desegregation was to be carried out. Known as Brown II, the decree directs that schools be desegregated under the control of Federal district judges "with all deliberate speed."

Brown II was intended to work out the mechanics of desegregation. Due to the vagueness of the phrase "all deliberate speed" however, many states were able to stall the Court’s order to desegregate their schools. The legal and social obstacles that southern states put in place and encouraged, in their effort to thwart integration, served as a catalyst for the student protests that launched the Civil Rights Movement.

On May 31, 1955 – one year and two weeks after the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional – Chief Justice Earl Warren issued this decree, ruling how desegregation was to be carried out. Known as Brown II, the decree directs that schools be desegregated under the control of Federal district judges "with all deliberate speed."

Brown II was intended to work out the mechanics of desegregation. Due to the vagueness of the phrase "all deliberate speed" however, many states were able to stall the Court’s order to desegregate their schools. The legal and social obstacles that southern states put in place and encouraged, in their effort to thwart integration, served as a catalyst for the student protests that launched the Civil Rights Movement.

Transcript

Supreme Court of the United StatesNo. 1 ------ , October Term 1954

Oliver Brown, Mrs. Richard Lawton, Mrs. Sadie Emmanuel et al.. Appellants,

vs.

Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Kansas.

This case came on to be heard on the transcript of the records from the United States District Court for the District of Kansas, and was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof, It is ordered and adjudged by this Court that the judgement of the said District Court in this cause be, and the same is hereby, reversed with costs; and that this cause be, and the is hereby, remanded to the said District Court to take such proceedings and enter such orders and decrees consistent with the opinions of this Court as are necessary and proper to admit to public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed the parties to this case.

Per Mr. Chief Justice Warren,

May 31, 1955

This primary source comes from the Records of the Supreme Court of the United States.

National Archives Identifier: 596300

Full Citation: Judgment, Brown v. Board of Education; 5/31/1955; Case File for Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka et al.; Appellate Jurisdiction Case Files, 1792 - 2010; Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/judgment-brown-v-board, April 20, 2024]Judgment, Brown v. Board of Education

Page 1

Judgment, Brown v. Board of Education

Page 2

Document

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, an Act to Abolish the Offices of the Director and Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget

1973

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 2127368

Full Citation: Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, an Act to Abolish the Offices of the Director and Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget; 1973; Records of the U.S. Senate, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/attempted-override-of-president-richard-nixons-veto-of-s-518-an-act-to-abolish-the-offices-of-the-director-and-deputy-director-of-the-office-of-management-and-budget, April 20, 2024]Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, an Act to Abolish the Offices of the Director and Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget

Page 1

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, an Act to Abolish the Offices of the Director and Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget

Page 2

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, an Act to Abolish the Offices of the Director and Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget

Page 3

Attempted Override of President Richard Nixon's Veto of S. 518, an Act to Abolish the Offices of the Director and Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget

Page 4

Document

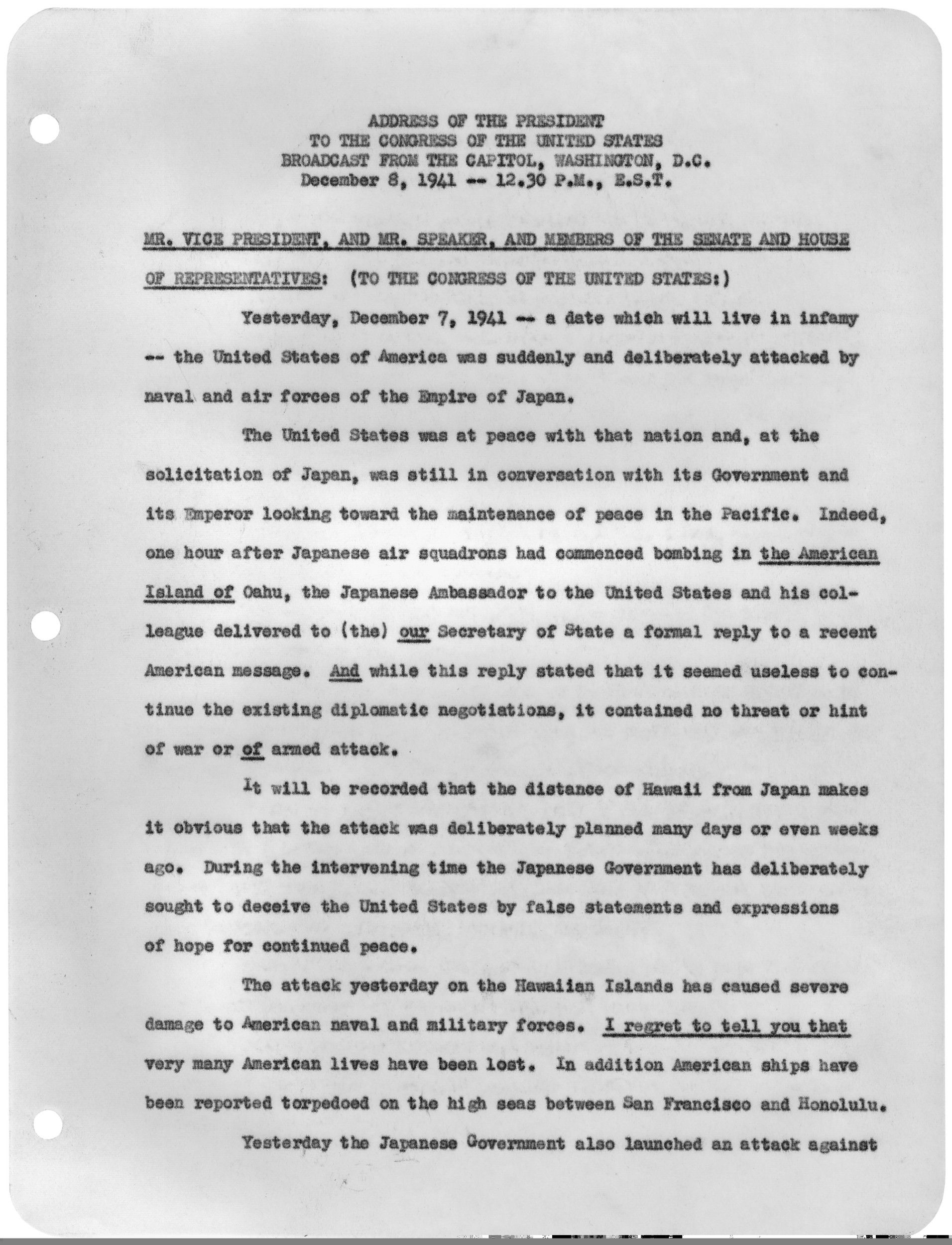

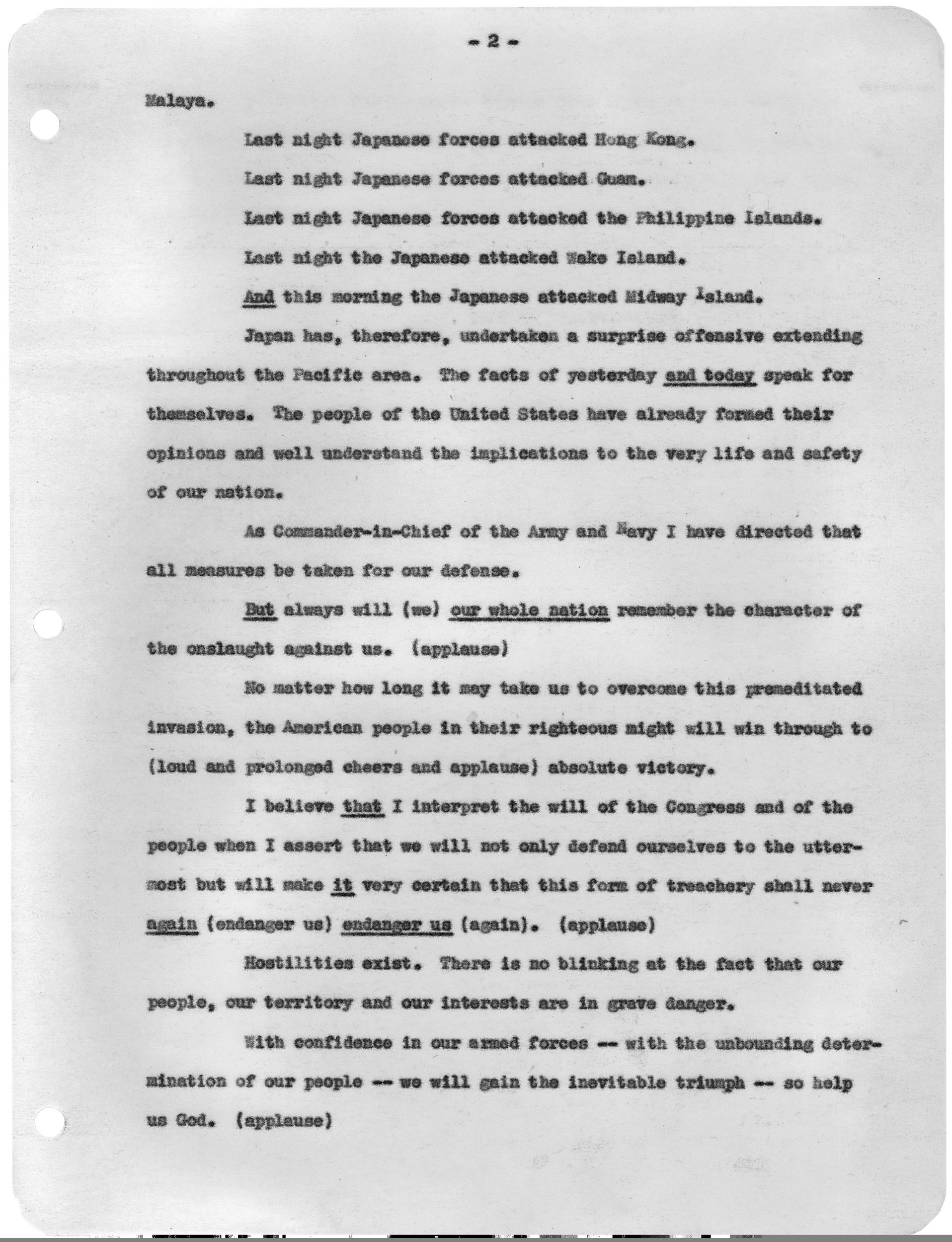

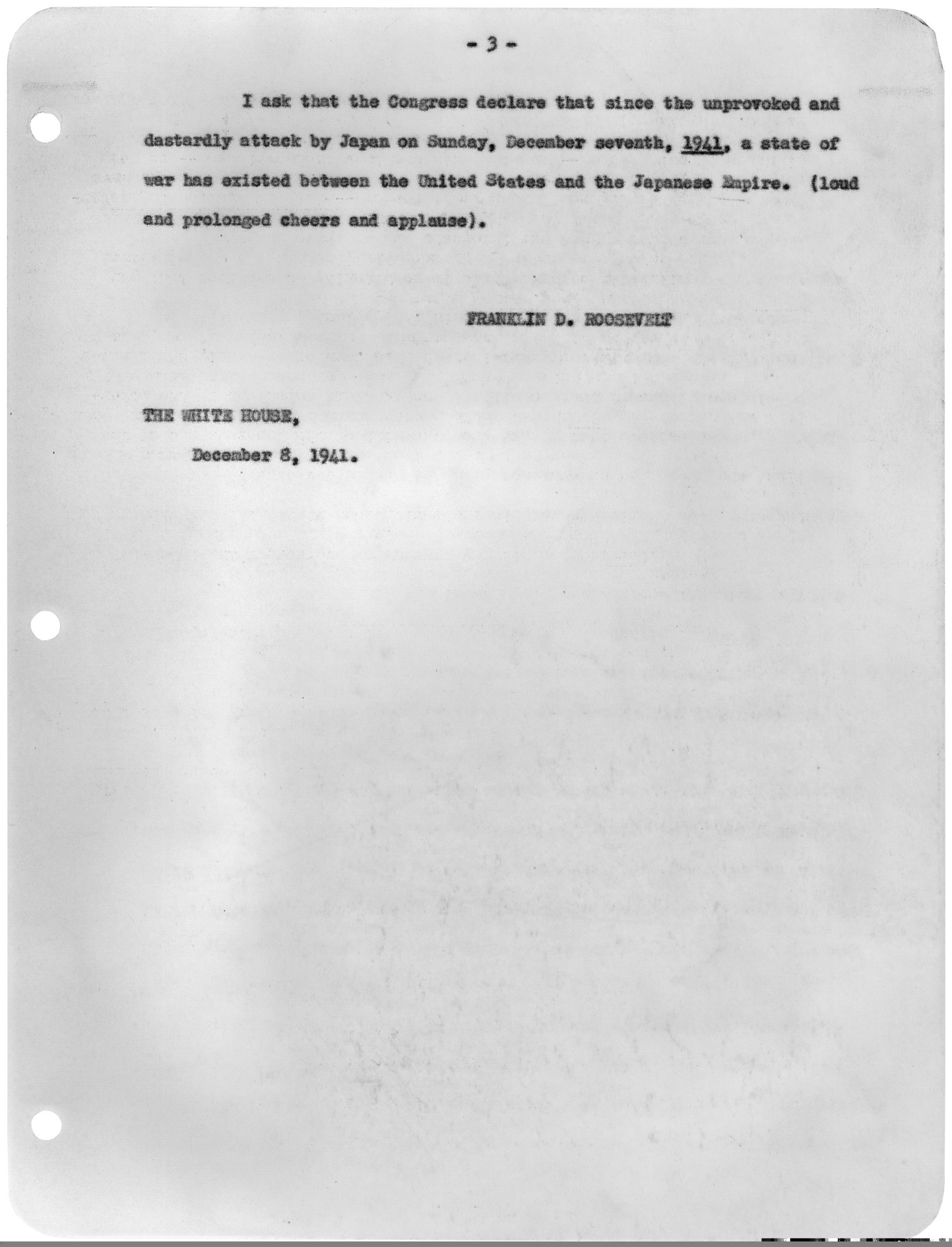

Transcript of Message to Congress Requesting Declaration of War Against Japan

12/8/1941

This is a transcript of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Message to Congress requesting a declaration of war against Japan. Roosevelt delivered the address to a Joint Session of Congress on December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. A White House stenographer transcribed the speech as it was delivered. Words that Roosevelt added to his speech are underlined. Words in parentheses were in his prepared text but were omitted during delivery. The transcript also notes where the audience applauded.

This primary source comes from the Collection FDR-PPF: Papers as President, President's Personal File.

National Archives Identifier: 197365

Full Citation: Transcript of Message to Congress Requesting Declaration of War Against Japan; 12/8/1941; Collection FDR-PPF: Papers as President, President's Personal File, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/transcript-of-message-to-congress-requesting-declaration-of-war-against-japan, April 20, 2024]Transcript of Message to Congress Requesting Declaration of War Against Japan

Page 1

Transcript of Message to Congress Requesting Declaration of War Against Japan

Page 2

Transcript of Message to Congress Requesting Declaration of War Against Japan

Page 3

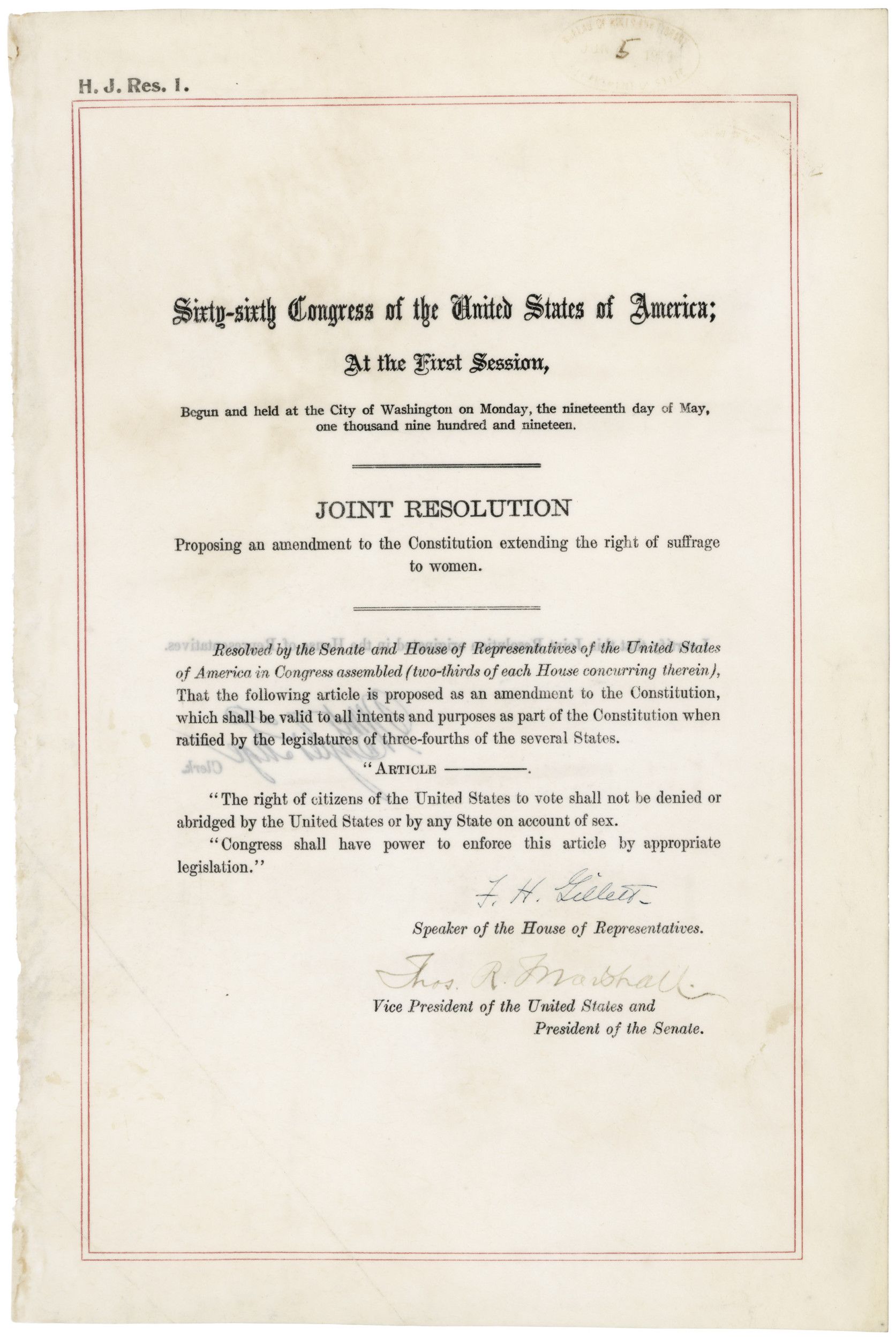

Document

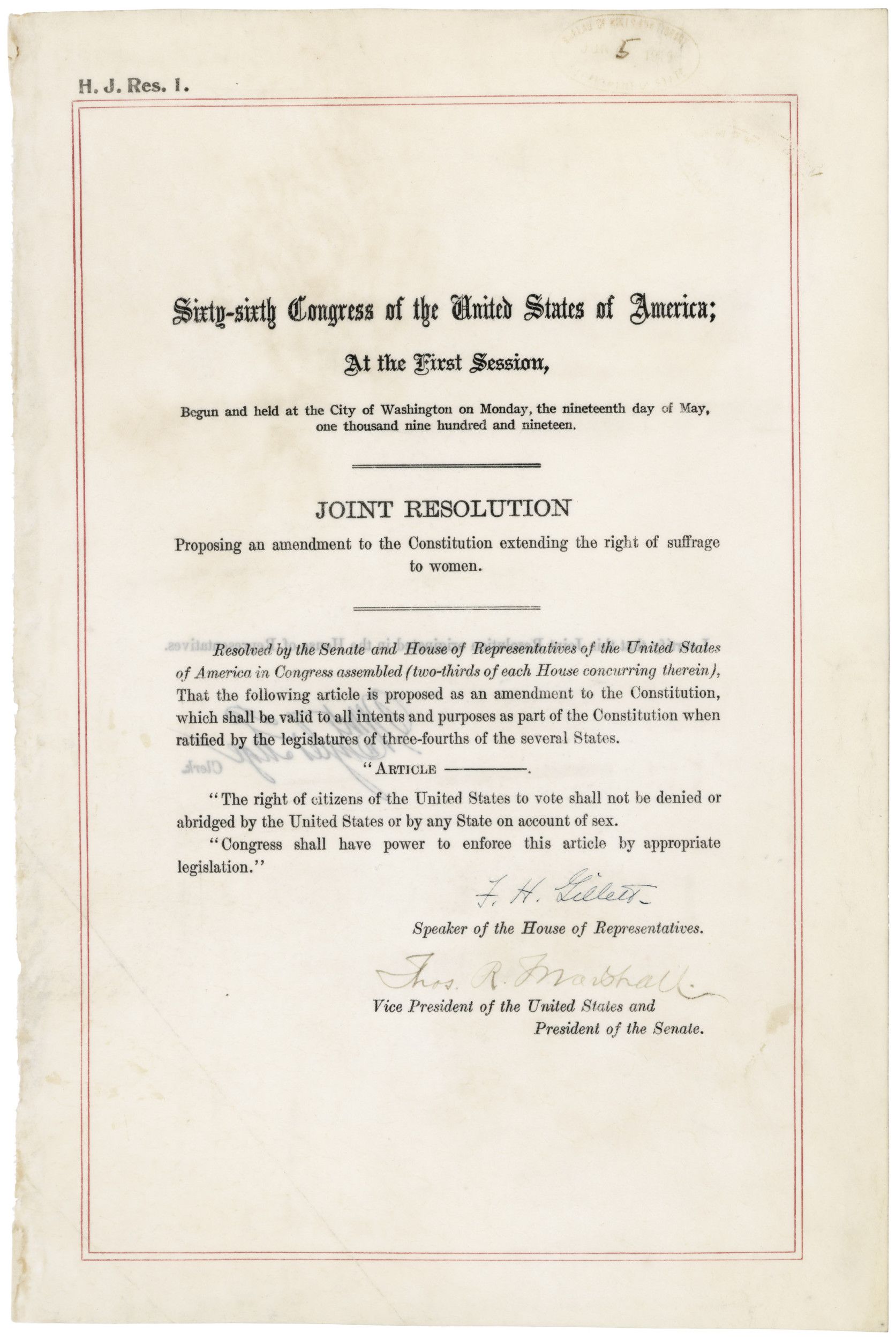

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

6/4/1919

This document shows approval by both the House of Representatives and the Senate (by two-thirds vote in each house) of the proposed 19th amendment to the Constitution that "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation."

Despite opposition from southern states, both houses of Congress passed the 19th Amendment, proposing full voting rights for women, and sent it to the states for ratification. Three-fourths of the states, or 36 states at that time, had to ratify the amendment before it could be added to the Constitution. On August 18, 1920, after calling a special session of the state legislature, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, thereby legally enfranchising one-half of the people.

The campaign for woman suffrage was long, difficult, and sometimes dramatic, yet ratification did not ensure full enfranchisement. Many women remained unable to vote long into the 20th century because of discriminatory state voting laws.

The document shown here is the Congressional joint resolution proposing the 19th Amendment. A joint resolution is a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification.

Despite opposition from southern states, both houses of Congress passed the 19th Amendment, proposing full voting rights for women, and sent it to the states for ratification. Three-fourths of the states, or 36 states at that time, had to ratify the amendment before it could be added to the Constitution. On August 18, 1920, after calling a special session of the state legislature, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, thereby legally enfranchising one-half of the people.

The campaign for woman suffrage was long, difficult, and sometimes dramatic, yet ratification did not ensure full enfranchisement. Many women remained unable to vote long into the 20th century because of discriminatory state voting laws.

The document shown here is the Congressional joint resolution proposing the 19th Amendment. A joint resolution is a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification.

Transcript

Sixty-sixth Congress of the United States of America; At the First Session,Begun and held at the City of Washington on Monday, the nineteenth day of May, one thousand nine hundred and nineteen.

JOINT RESOLUTION

Proposing an amendment to the Constitution extending the right of suffrage to women.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled (two-thirds of each House concurring therein), That the following article is proposed as an amendment to the Constitution, which shall be valid to all intents and purposes as part of the Constitution when ratified by the legislature of three-fourths of the several States.

"ARTICLE ————.

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation."

[endorsements]

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 596314

Full Citation: Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; 6/4/1919; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/nineteenth-amendment, April 20, 2024]Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1

Document

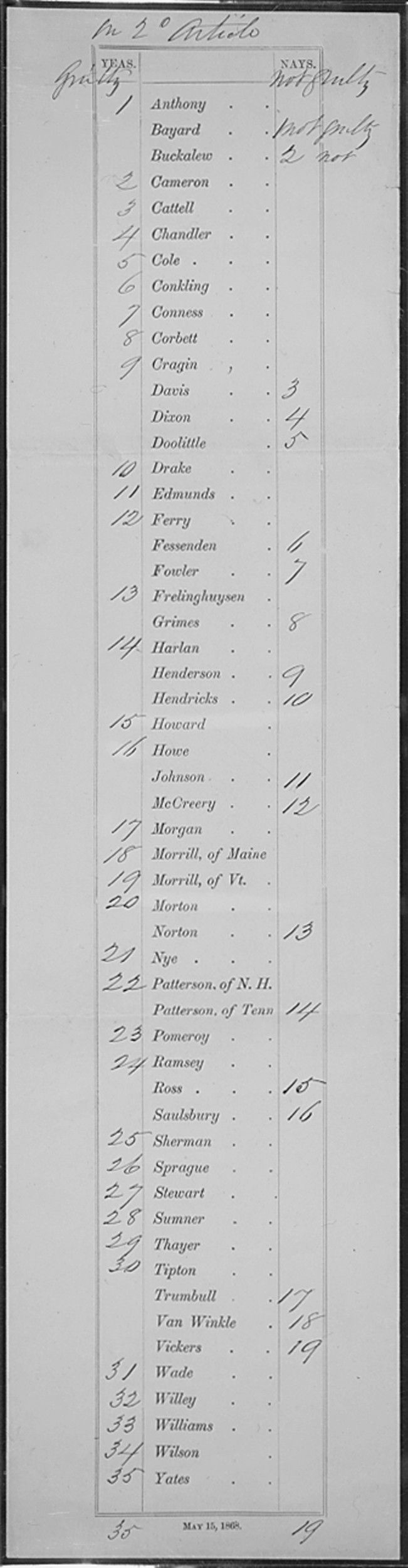

Roll call votes relating to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson on Articles II, III, and XI

5/26/1868

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 306275

Full Citation: Roll call votes relating to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson on Articles II, III, and XI; 5/26/1868; Records of the U.S. Senate, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/roll-call-votes-relating-to-the-impeachment-of-president-andrew-johnson-on-articles-ii-iii-and-xi, April 20, 2024]Roll call votes relating to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson on Articles II, III, and XI

Page 1

Roll call votes relating to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson on Articles II, III, and XI

Page 2

Roll call votes relating to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson on Articles II, III, and XI

Page 3

Roll call votes relating to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson on Articles II, III, and XI

Page 4

Document

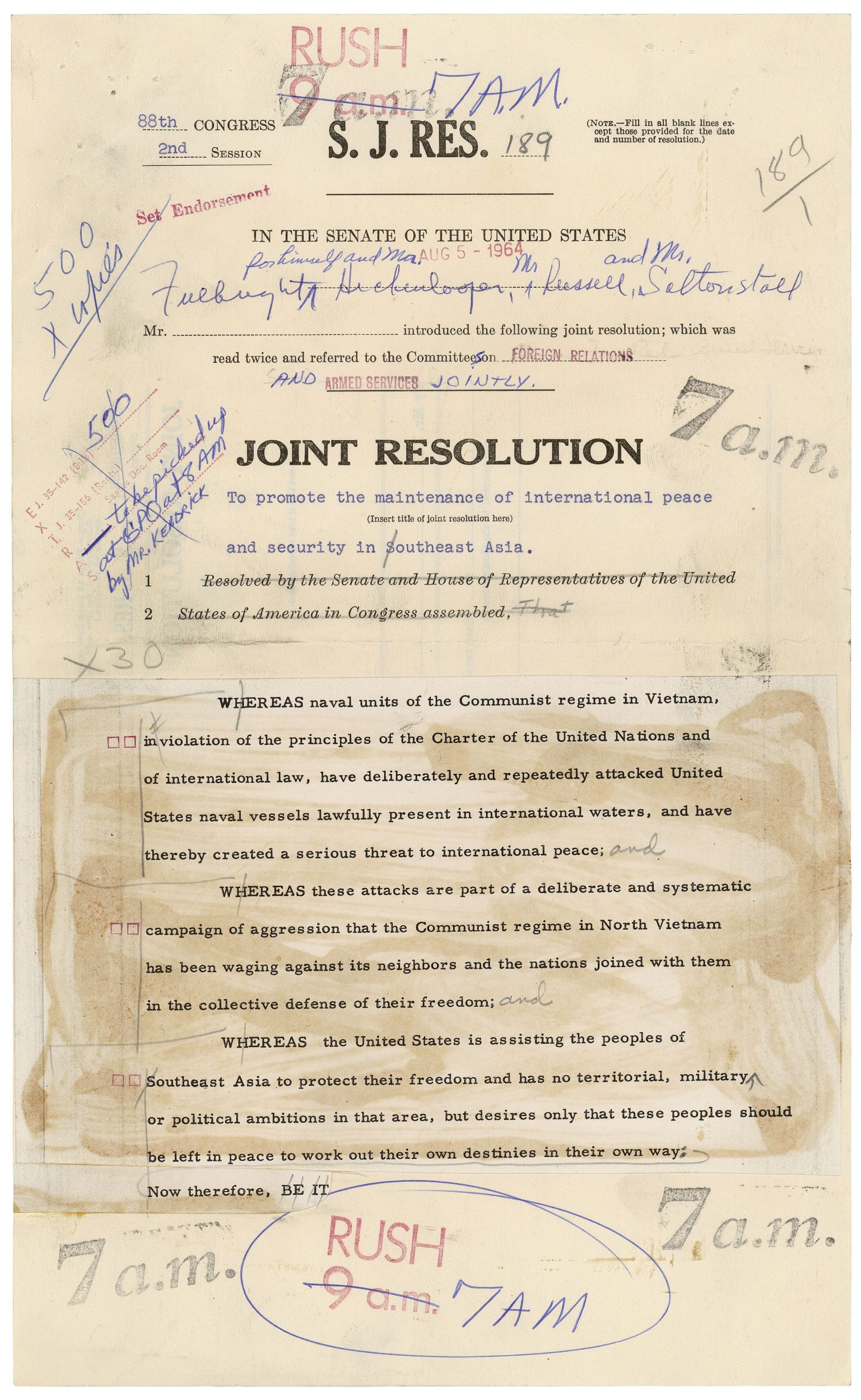

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Introduced, S.J. Res. 189

8/4/1964

On the evening of August 4, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson addressed the nation in a televised speech in which he stated that U.S. ships had been attacked twice in international waters in the Gulf of Tonkin near North Vietnam. The following morning, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was introduced in the Senate.

Although the version shown here is the original draft resolution, the language was not amended and therefore reads the same as the final version that was signed into law August 10, 1964. When Congress passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, they gave Johnson unprecedented power to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

There was little debate as legislators considered two incidents that had happened in the Gulf of Tonkin in the preceding days. On August 2 – the first Tonkin Gulf incident – North Vietnamese torpedo boats were spotted and attacked the destroyer USS Maddox. The Maddox was conducting electronic eavesdropping on North Vietnam to assist South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) commando raids on North Vietnamese targets, but that wasn't publicly known at the time. Historians now suspect the North Vietnamese boats had set out to attack an ARVN raid in progress when it encountered the Maddox.

On August 4, the USS Maddox captain reported a second incident, that he was “under continuous torpedo attack.” He later cabled “freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonarmen may have accounted for many reports,” but Defense Secretary Robert McNamara did not report the captain’s doubts to President Johnson. (A 2002 National Security Agency report made available in 2007 confirmed the August 2 attack, but concluded the August 4 attack never happened.)

Johnson portrayed confrontations between U.S. and North Vietnamese ships off the coast of North Vietnam as unprovoked aggression when he addressed Congress. When contrary information later surfaced, many believed Congress had been conned. It was too late.

The Gulf of Tonkin act became more controversial as opposition to the war mounted. A Senate investigation revealed that the Maddox had been on an intelligence mission in Tonkin Gulf, contradicting Johnson’s denial of U.S. Navy support of such missions. The Resolution was repealed in 1971 in an attempt to curtail President Nixon’s power to continue the war.

Although the version shown here is the original draft resolution, the language was not amended and therefore reads the same as the final version that was signed into law August 10, 1964. When Congress passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, they gave Johnson unprecedented power to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

There was little debate as legislators considered two incidents that had happened in the Gulf of Tonkin in the preceding days. On August 2 – the first Tonkin Gulf incident – North Vietnamese torpedo boats were spotted and attacked the destroyer USS Maddox. The Maddox was conducting electronic eavesdropping on North Vietnam to assist South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) commando raids on North Vietnamese targets, but that wasn't publicly known at the time. Historians now suspect the North Vietnamese boats had set out to attack an ARVN raid in progress when it encountered the Maddox.

On August 4, the USS Maddox captain reported a second incident, that he was “under continuous torpedo attack.” He later cabled “freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonarmen may have accounted for many reports,” but Defense Secretary Robert McNamara did not report the captain’s doubts to President Johnson. (A 2002 National Security Agency report made available in 2007 confirmed the August 2 attack, but concluded the August 4 attack never happened.)

Johnson portrayed confrontations between U.S. and North Vietnamese ships off the coast of North Vietnam as unprovoked aggression when he addressed Congress. When contrary information later surfaced, many believed Congress had been conned. It was too late.

The Gulf of Tonkin act became more controversial as opposition to the war mounted. A Senate investigation revealed that the Maddox had been on an intelligence mission in Tonkin Gulf, contradicting Johnson’s denial of U.S. Navy support of such missions. The Resolution was repealed in 1971 in an attempt to curtail President Nixon’s power to continue the war.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 2127364

Full Citation: Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Introduced, S.J. Res. 189; 8/4/1964; (SEN88A-B2); Bills and Resolutions Originating in the Senate, 1789 - 2002; Records of the U.S. Senate, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/tonkin-resolution, April 20, 2024]Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Introduced, S.J. Res. 189

Page 1

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Introduced, S.J. Res. 189

Page 2

Document

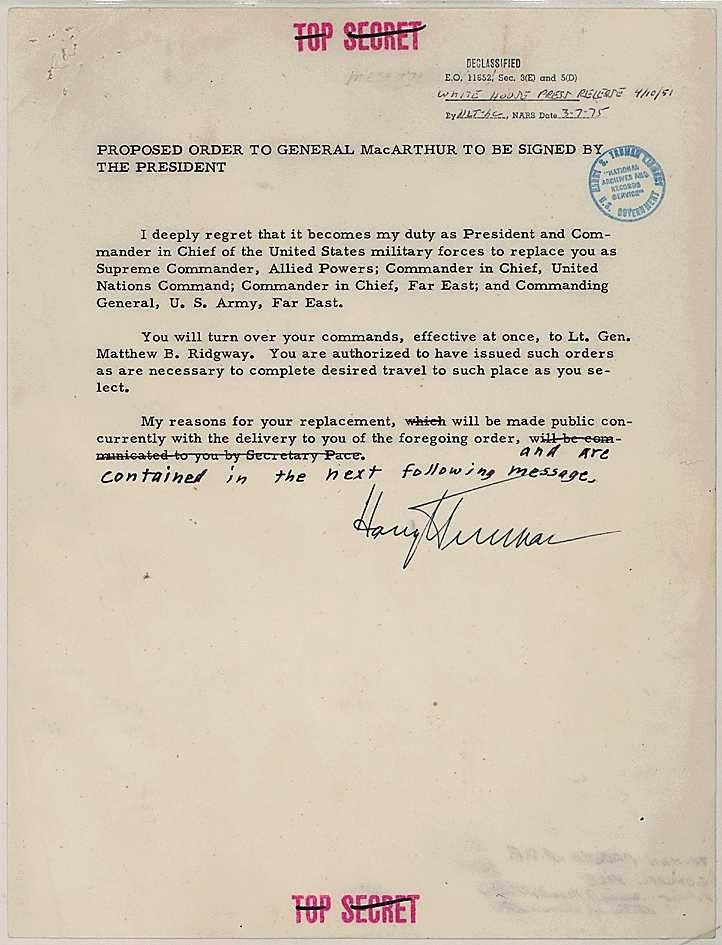

Proposed Orders and Statement on Dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur

4/11/1951

Formerly classified "Top Secret," this document is President Harry Truman's order relieving General Douglas MacArthur of his Korean War commands due to insubordination, and designating General Matthew Ridgway as his successor. It includes a statement explaining MacArthur's dismissal.

It was featured in the article “Truman’s Firing of General Douglas MacArthur during the Korean War” in the November/December 2000 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

It was featured in the article “Truman’s Firing of General Douglas MacArthur during the Korean War” in the November/December 2000 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

This primary source comes from the Collection HST-PSF: President's Secretary's Files (Truman Administration), 1945 - 1960.

National Archives Identifier: 201516

Full Citation: Proposed Orders and Statement on Dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur; 4/11/1951; General Files, 1945 - 1953; Collection HST-PSF: President's Secretary's Files (Truman Administration), 1945 - 1960, ; Harry S. Truman Library, Independence, MO. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/dismissal-general-macarthur, April 20, 2024]Proposed Orders and Statement on Dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur

Page 1

Proposed Orders and Statement on Dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur

Page 2

Proposed Orders and Statement on Dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur

Page 3

Document

Message of President Abraham Lincoln Nominating Ulysses S. Grant to Be Lieutenant General of the Army

3/1/1864

With this message, President Abraham Lincoln forwarded Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s name to the U.S. Senate for consideration for promotion to the rank of lieutenant general on February 29, 1864. Congress had recently authorized the rank, held previously only by George Washington.

Transcript

Executive Mansion,Washington, February, 29, 1864

To the Senate of the United States,

I nominate Ulysses. S. Grant now a Major General in the military service, to be Lieutenant General in the Army of the United States.

Abraham Lincoln

Cont. March 2

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 306310

Full Citation: Message of President Abraham Lincoln Nominating Ulysses S. Grant to Be Lieutenant General of the Army; 3/1/1864; Records of the U.S. Senate, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/lincoln-nominating-grant-lieutenant-general-of-army, April 20, 2024]Message of President Abraham Lincoln Nominating Ulysses S. Grant to Be Lieutenant General of the Army

Page 2

Document

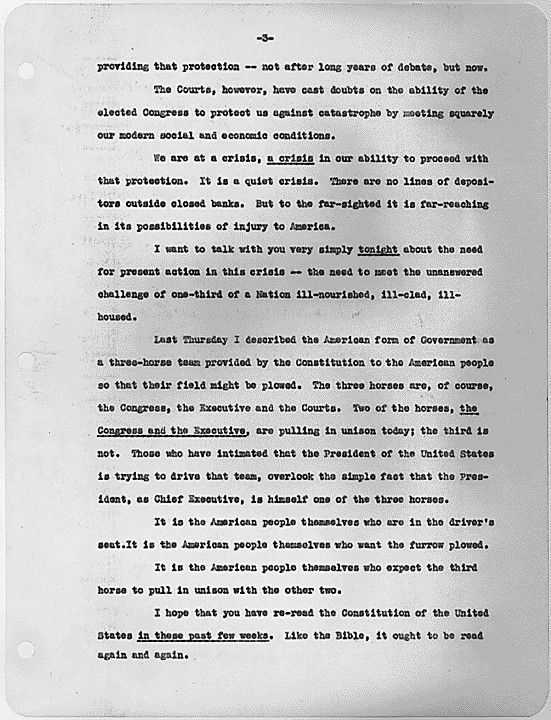

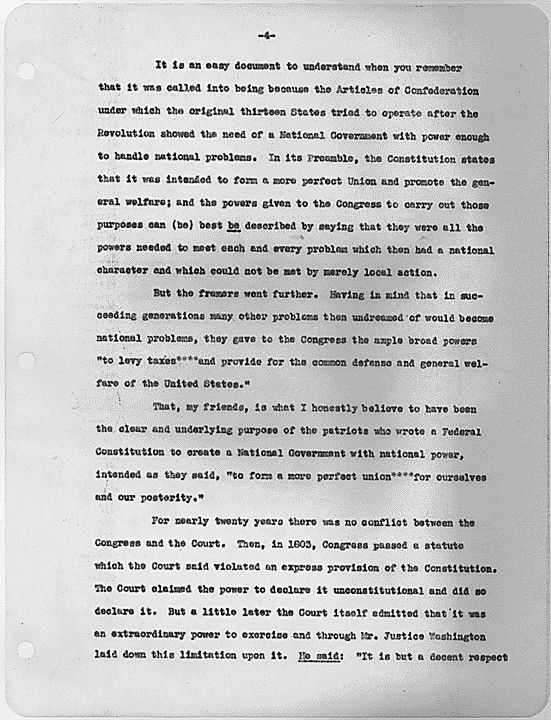

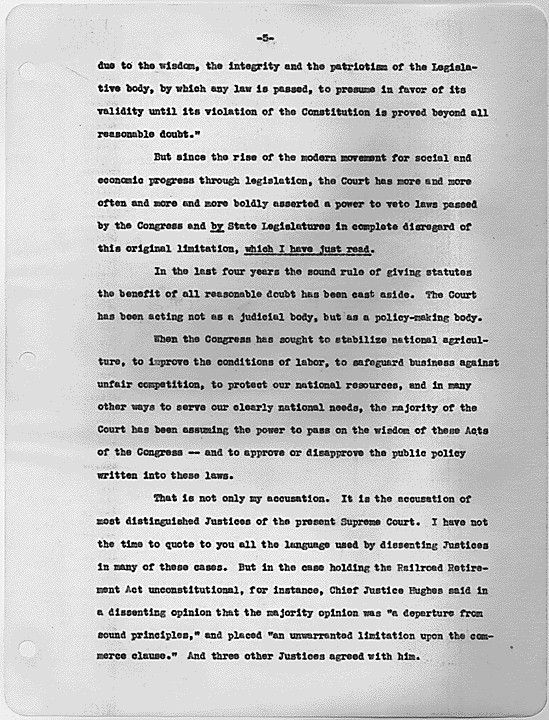

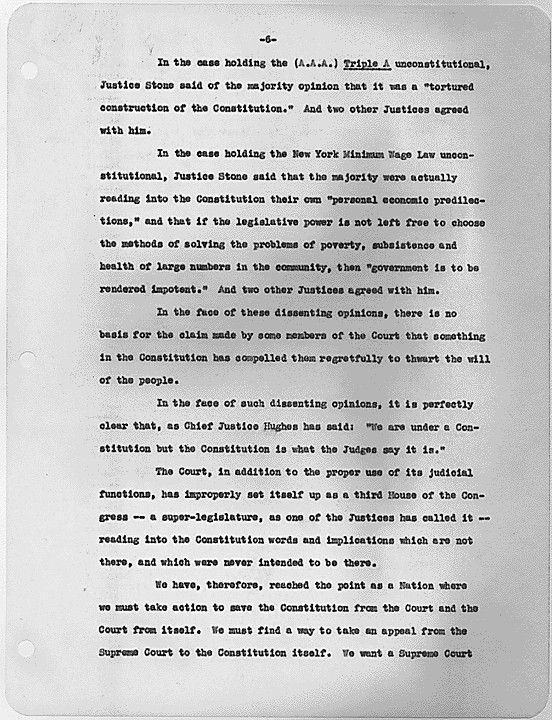

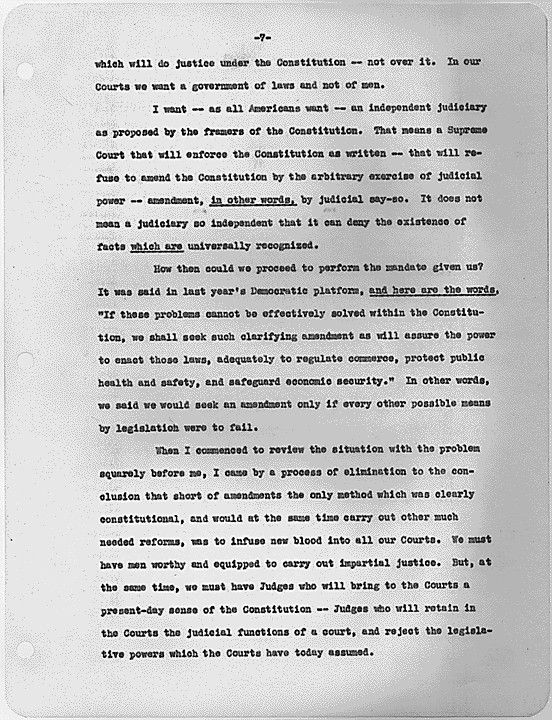

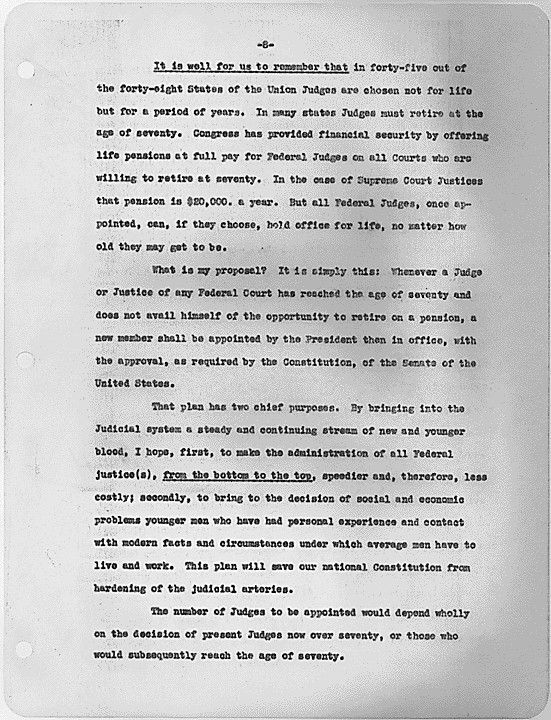

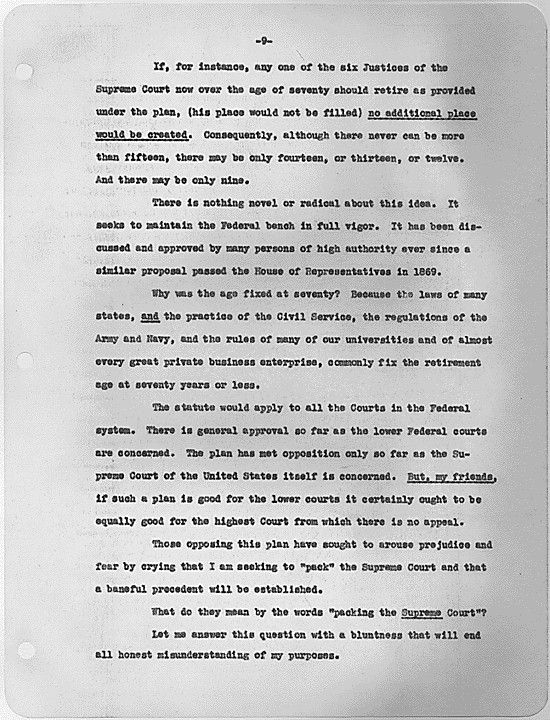

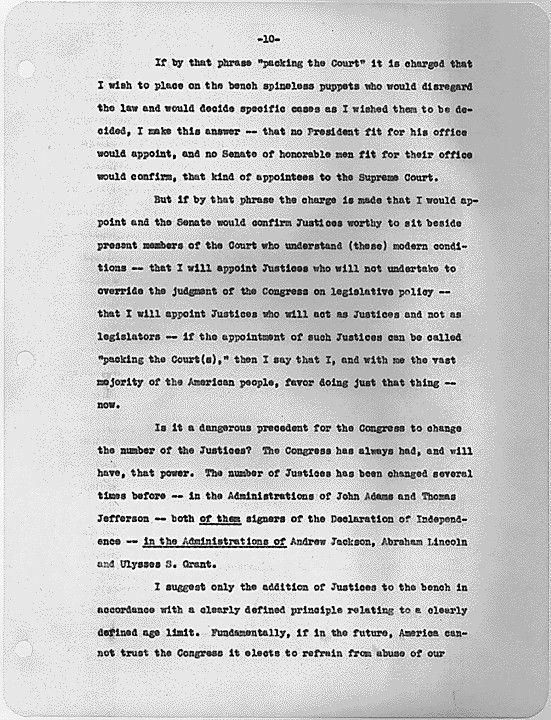

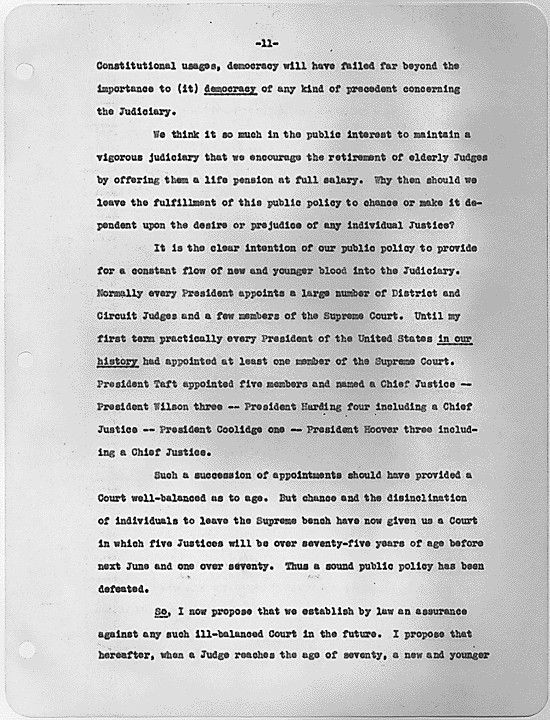

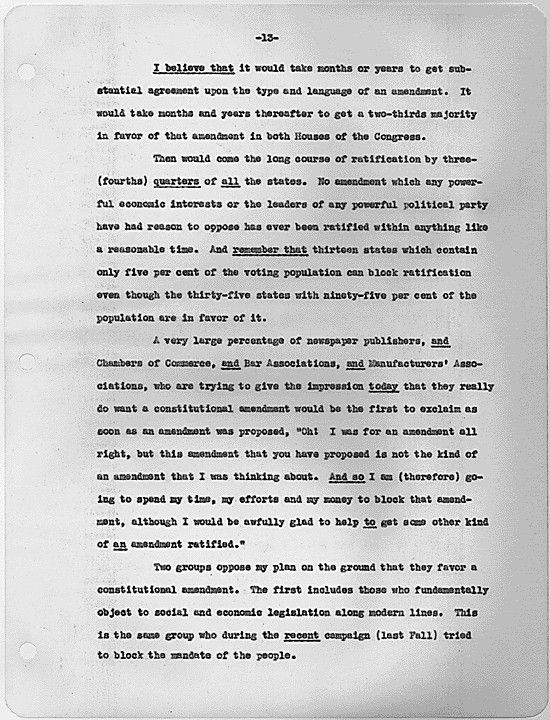

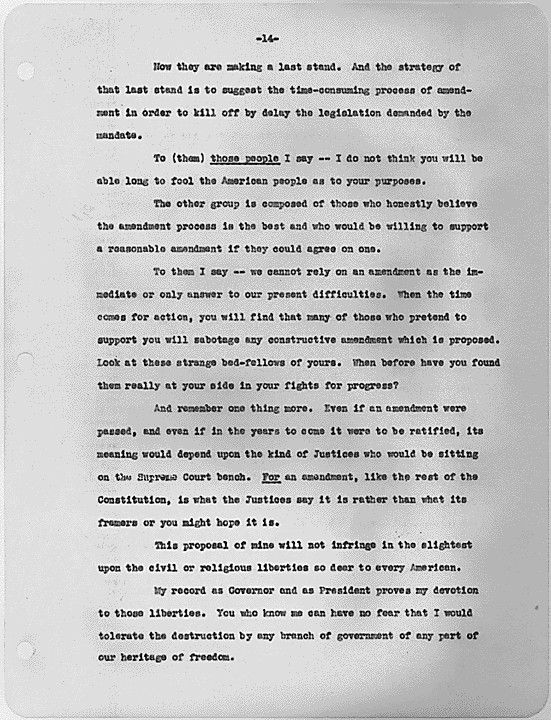

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

3/9/1937

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats (there were 30 in all) were radio speeches he made describing important current events and political issues to the American people. This particular speech from 1937 expresses his hope that Congress will create legislation for the reorganization of the Supreme Court to increase the number of Justices. Roosevelt introduced the notion of “Court packing,” in which for every Justice on the Supreme Court over 70 years of age, a new Justice would be added.

This primary source comes from the Collection FDR-PPF: Papers as President, President's Personal File.

National Archives Identifier: 197310

Full Citation: Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary; 3/9/1937; Collection FDR-PPF: Papers as President, President's Personal File, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/fireside-chat-on-reorganization-of-the-judiciary, April 20, 2024]Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 1

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 2

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 3

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 4

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 5

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 6

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 7

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 8

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 9

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 10

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 11

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 12

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 13

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 14

Fireside Chat on Reorganization of the Judiciary

Page 15