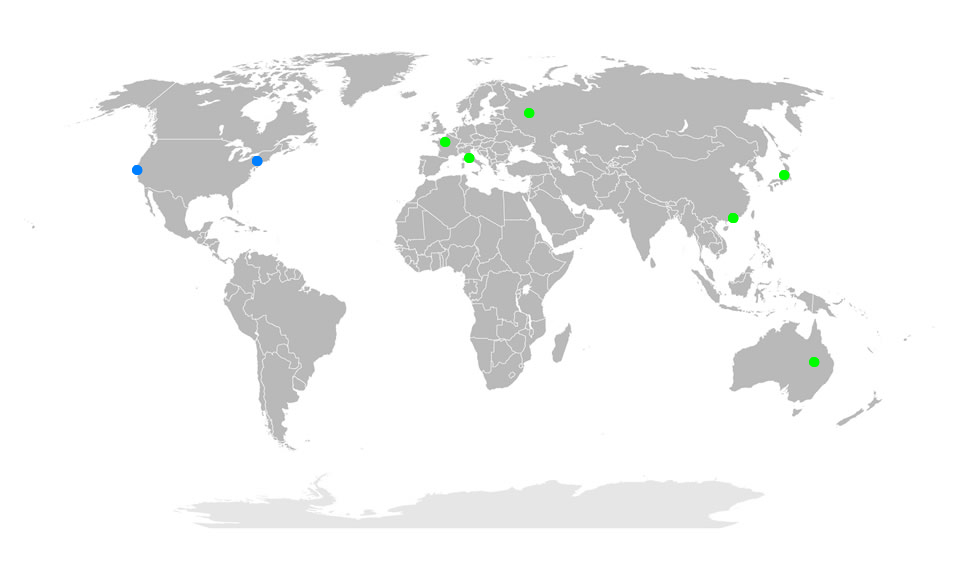

Ports of Immigration: Angel Island and Ellis Island

Mapping History

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

Immigration is a cornerstone of American history. People immigrate to the United States from all over the world and for many different reasons. From the late 1800s through the mid-1900s, there were many ports of entry into the United States (where people come into the country). Two of the largest were Ellis Island and Angel Island.

In this activity you will learn about the immigration process, ports of entry, and see how the United States is connected to different parts of the world.

In this activity you will learn about the immigration process, ports of entry, and see how the United States is connected to different parts of the world.

- Find the two photographs below the map. Click on the orange "Open in New Window" icon for each and read about the two different ports of entry for immigrants coming to America. Then move each photograph to a blue dot on the map.

- Click on each of the other documents. Look at them closely and read the information provided. Move each one to a green dot on the map — pick the dot for the country of departure for the immigrant (where they sailed from), not necessarily their home country. (One document is a report from a U.S. immigration officer about why people were leaving their country. Put it on the country it was written about.)

As you read the documents about these immigrants, take note of which port of entry they passed through, why they wanted to come to America, and why they were denied entry (not allowed to come).

Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

Ports of Immigration: Angel Island and Ellis Island

Mapping History

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Consider how each document or piece of text relates to the image shown below. Write the corresponding document or text number on the image where you think it belongs. (Some may be placed for you already.) Write your conclusion response in the space provided.

1

Activity Element

2

Activity Element

3

Activity Element

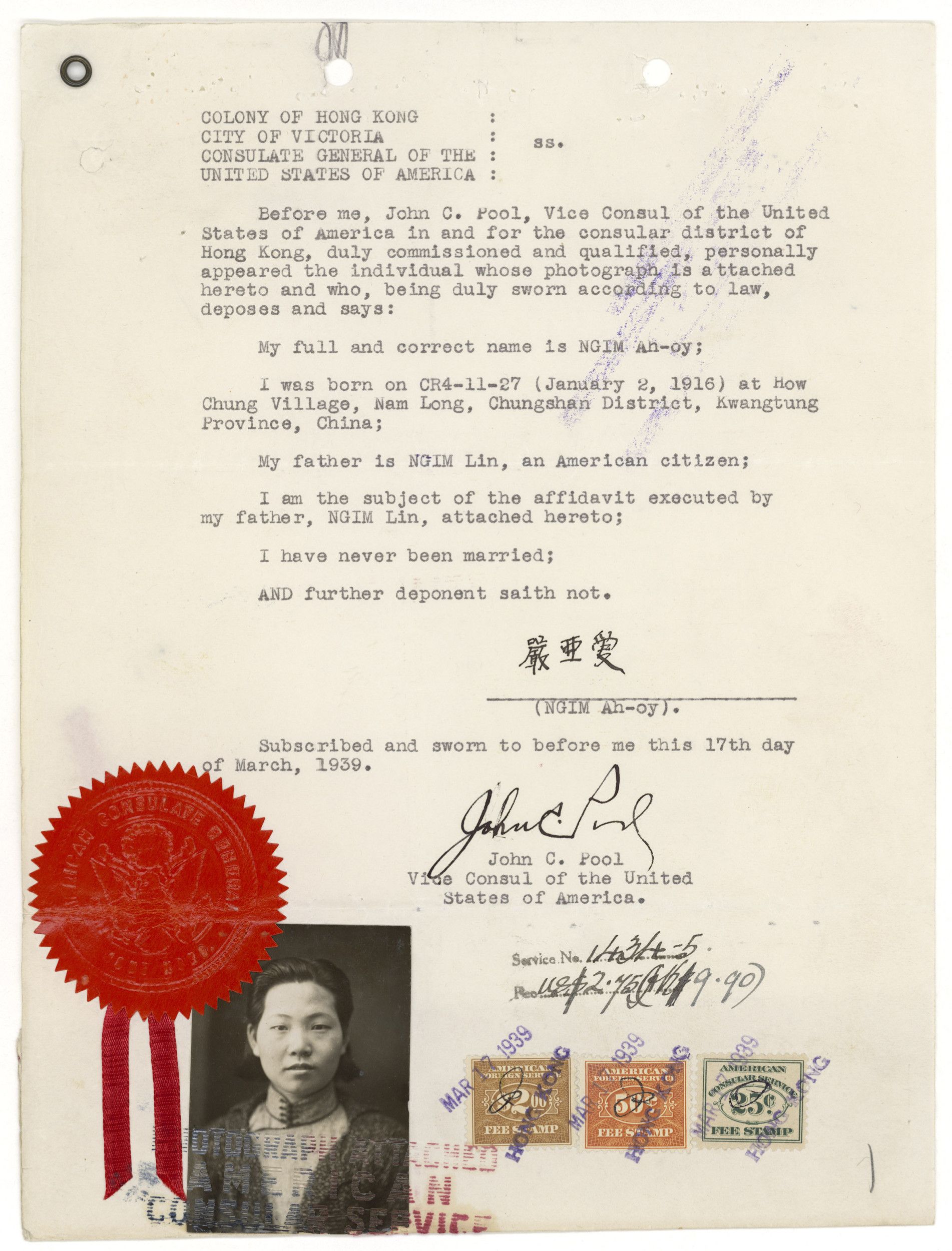

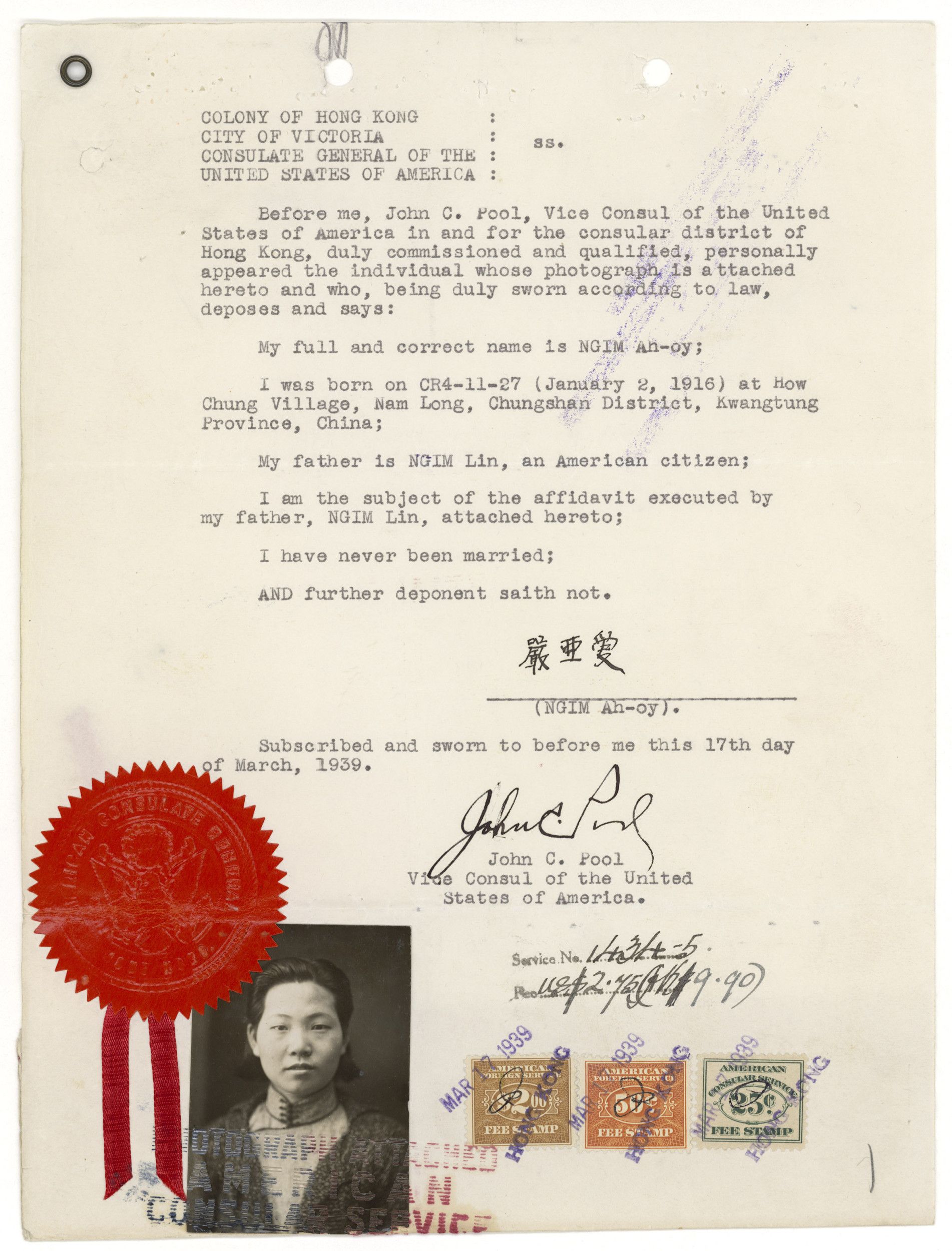

Affidavit of Ngim Ah Oy Filed with the United States Consulate in Hong Kong

Page 1

4

Activity Element

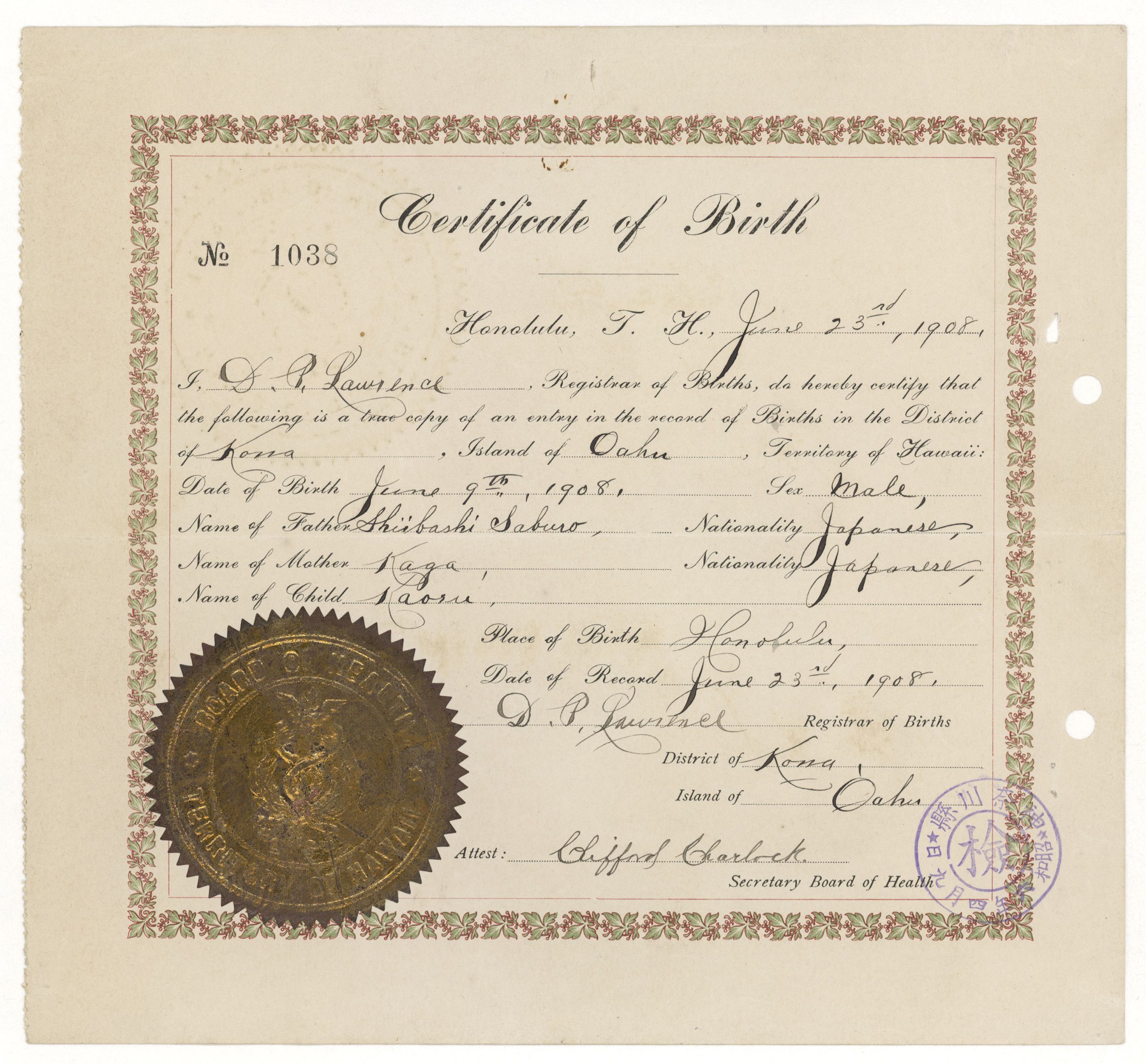

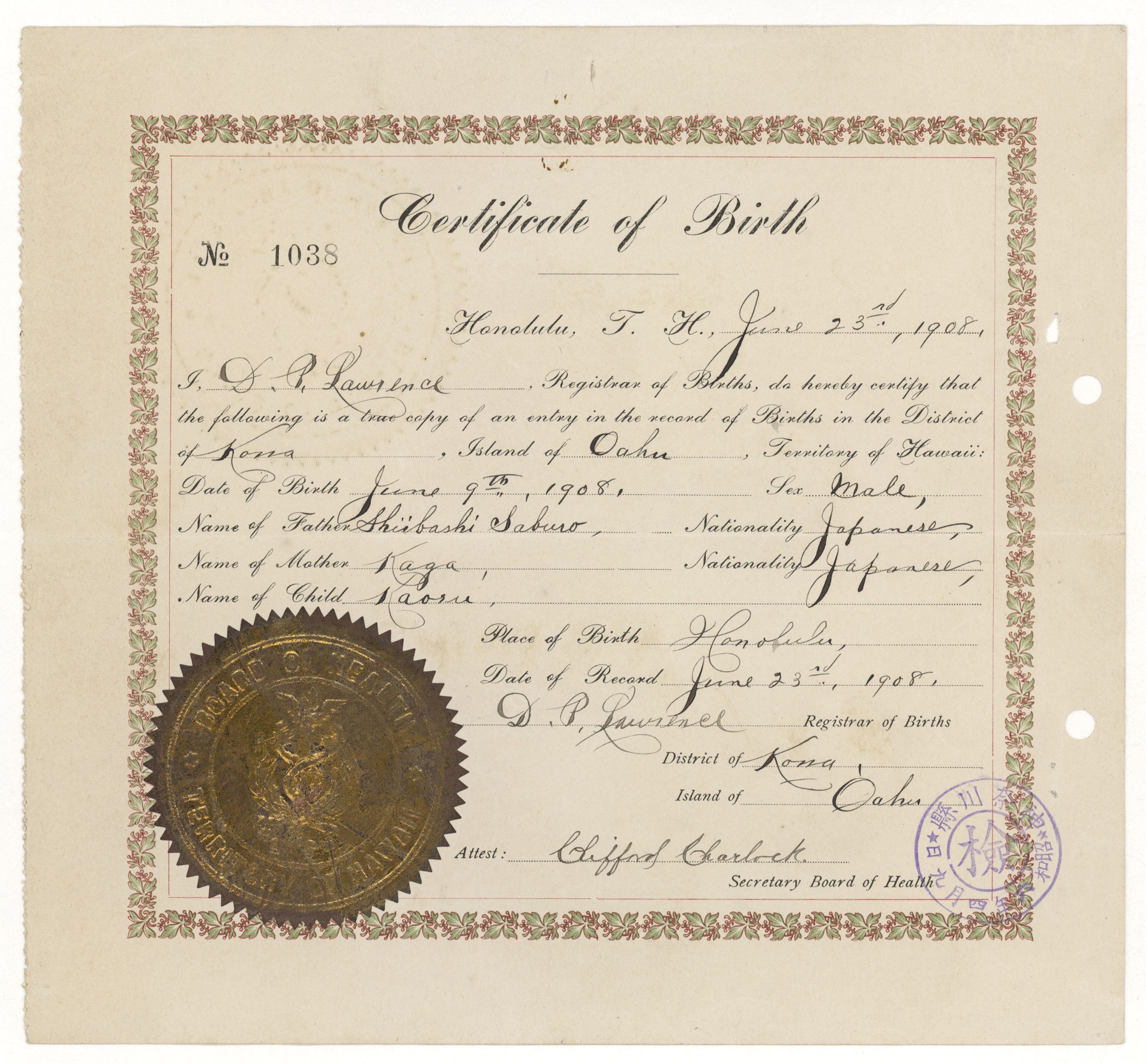

Certificate of Birth of Kaoru Shiibashi

Page 1

5

Activity Element

Immigrants Arriving at the Immigration Station on Angel Island

Page 1

6

Activity Element

Transcript of Meeting of Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station with Enclosed Application to Enter the United States and Photograph

Page 1

7

Activity Element

A Group of Immigrants Outside a Building on Ellis Island

Page 1

8

Activity Element

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 1

9

Activity Element

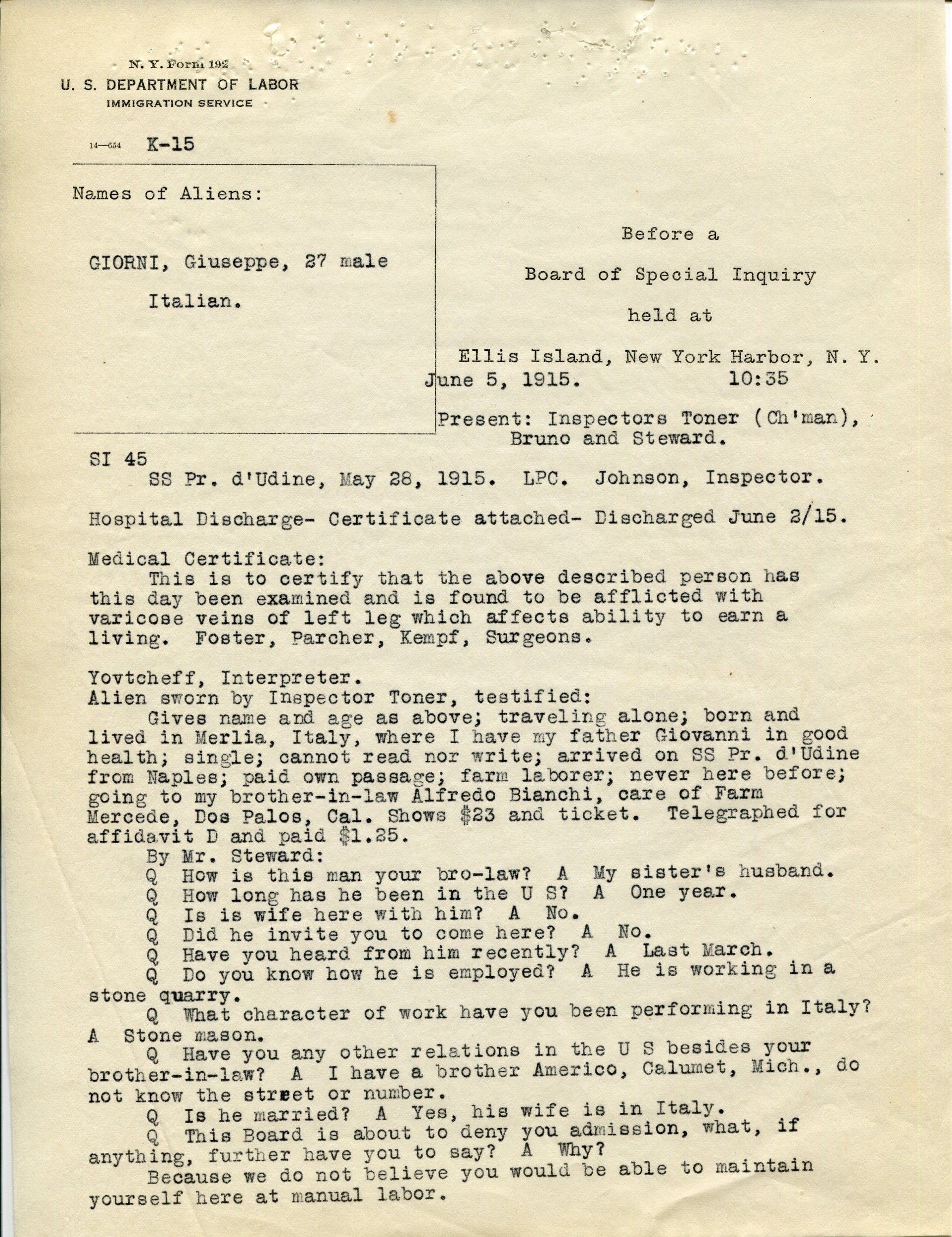

Report of Special Inquiry Held at Ellis Island Regarding Deportation of Italian Immigrants

Page 1

10

Activity Element

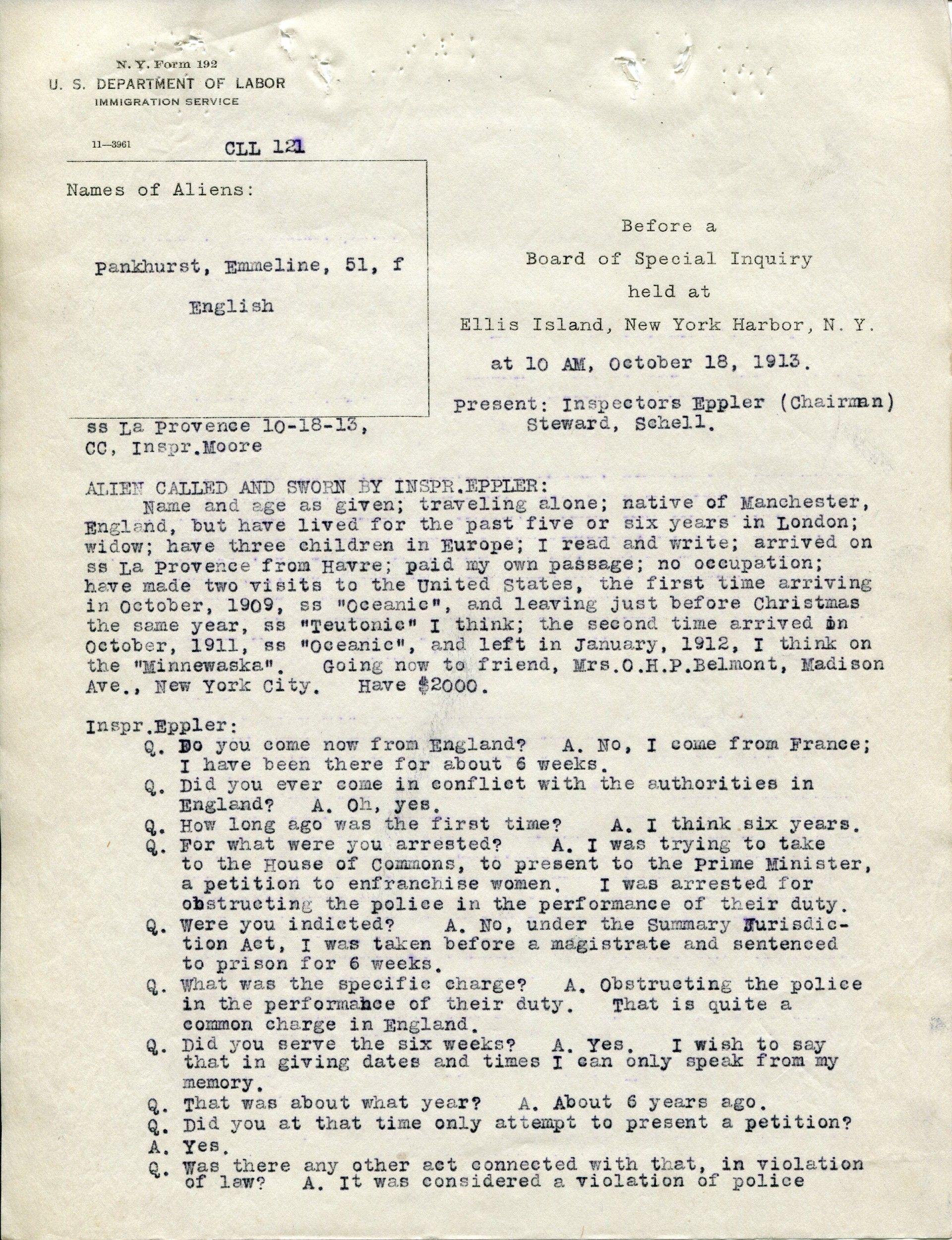

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst`s Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 1

Conclusion

Ports of Immigration: Angel Island and Ellis Island

Mapping History

Answer the following questions based on what you learned about ports of entry and the immigration experience.

- Based on the documents, what part of the world did people who passed through Ellis Island come from?

- Based on the documents, what part of the world did people who passed through Angel Island come from?

- What were some of the reasons why immigrants wanted to enter the United States?

- What were some of the reasons immigrants were denied entry into the United States?

Your Response

Document

A Group of Immigrants Outside a Building on Ellis Island

This undated photograph captures a group of immigrants outside a building on Ellis Island. The Immigration Station at Ellis Island in New York Harbor was the major East Coast processing center for immigrants who came to the United States between 1892 and 1924. An estimated 20 million individuals began their new lives in America here.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Public Health Service.

National Archives Identifier: 595669

Full Citation: Photograph 90-G-125-3; A Group of Immigrants Outside a Building on Ellis Island; Public Health Service Historical Photograph File, 1880 - 1943; Records of the Public Health Service, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/outside-ellis-island, April 19, 2024]A Group of Immigrants Outside a Building on Ellis Island

Page 1

Document

Affidavit of Ngim Ah Oy Filed with the United States Consulate in Hong Kong

3/17/1939

Additional details from our exhibits and publications

Twenty-three year-old Lee Puey You arrived in San Francisco on April 13, 1939, claiming to be the daughter of a U.S. citizen. Traveling under the name Ngim Ah Oy, Lee had left her poverty-stricken family in war-ravaged China to marry Woo Tong, a widower 30 years her senior. Immigration officials interviewed her for three days about her family’s history, her village, her home, and her neighbors. When her answers differed from those of her “father,” officials ordered her deported. While Lee’s “family” appealed her case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, she spent 20 months on Angel Island. Years later, she recalled, “sitting at Angel Island, I must have cried a bowlful of tears.” Lee was deported in 1940, but in 1947, after the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Acts, she returned to the United States posing as a war bride to marry Woo Tong. When she finally met him, she discovered his wife was still alive. She was forced to live with the couple and work for them until Woo died in 1950. After Woo’s death, Lee Puey You met and married Fred Gin, and together they raised four children. In 1955, she was investigated for entering the country using false documents. Lee confessed to this, and was ordered deported, but this time, her appeals were successful. She was allowed to stay and became a U.S. citizen in 1959. See the letter Lee Puey You wrote to her father in 1939 that was seized by the Immigration Service and used as evidence that Ngim Ah Oy was trying to secretly match her and her father’s answers to questions asked by immigration inspectors. See an additional letter Lee Puey You wrote to her father months earlier on December 21, 1938 that was also seized as evidence.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

National Archives Identifier: 6587585

Full Citation: Affidavit of Ngim Ah Oy Filed with the United States Consulate in Hong Kong; 3/17/1939; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/affidavit-of-ngim-ah-oy-filed-with-the-united-states-consulate-in-hong-kong, April 19, 2024]Affidavit of Ngim Ah Oy Filed with the United States Consulate in Hong Kong

Page 1

Document

Certificate of Birth of Kaoru Shiibashi

6/23/1908

The 1907 “Gentlemen’s Agreement” between the United States and Japan prevented male Japanese laborers from emigrating to the United States. The 1924 National Origins Act effectively ended all Japanese immigration. Thus, American citizens of Japanese ancestry living in Japan, who could legally return to the United States, were in great demand to work on Japanese farms in California.

In 1931, Kaoru Shiibashi, a 23 year old Hawaiian-born man who had been taken to Japan as a toddler, sailed to San Francisco “to see my native land” and to work on a farm near San Jose, California. When he arrived, immigration inspectors detained him on Angel Island and launched an investigation into his U.S. citizenship. Kaoru provided them with a family photograph of himself as an infant that was taken in Hawaii and with a copy of his Hawaiian birth certificate. However, the inspectors became suspicious when interviews with him and his family differed and no one in Hawaii could identify him in the photograph.

Kaoru was initially denied entry, but he was eventually admitted on appeal, and worked as a farm laborer in the strawberry fields for the next 10 years. During World War II, he was among 120,000 Japanese Americans detained under Executive Order 9066. After his release from the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming, he returned to farm in California.

In 1931, Kaoru Shiibashi, a 23 year old Hawaiian-born man who had been taken to Japan as a toddler, sailed to San Francisco “to see my native land” and to work on a farm near San Jose, California. When he arrived, immigration inspectors detained him on Angel Island and launched an investigation into his U.S. citizenship. Kaoru provided them with a family photograph of himself as an infant that was taken in Hawaii and with a copy of his Hawaiian birth certificate. However, the inspectors became suspicious when interviews with him and his family differed and no one in Hawaii could identify him in the photograph.

Kaoru was initially denied entry, but he was eventually admitted on appeal, and worked as a farm laborer in the strawberry fields for the next 10 years. During World War II, he was among 120,000 Japanese Americans detained under Executive Order 9066. After his release from the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming, he returned to farm in California.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

National Archives Identifier: 6587579

Full Citation: Certificate of Birth of Kaoru Shiibashi; 6/23/1908; Immigration Arrival Investigation Case File for Kaoru Shiibashi (30309/27-5); Immigration Arrival Investigation Case Files, 1884–1944; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, ; National Archives at San Francisco, San Bruno, CA. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/certificate-of-birth-of-kaoru-shiibashi, April 19, 2024]Certificate of Birth of Kaoru Shiibashi

Page 1

Document

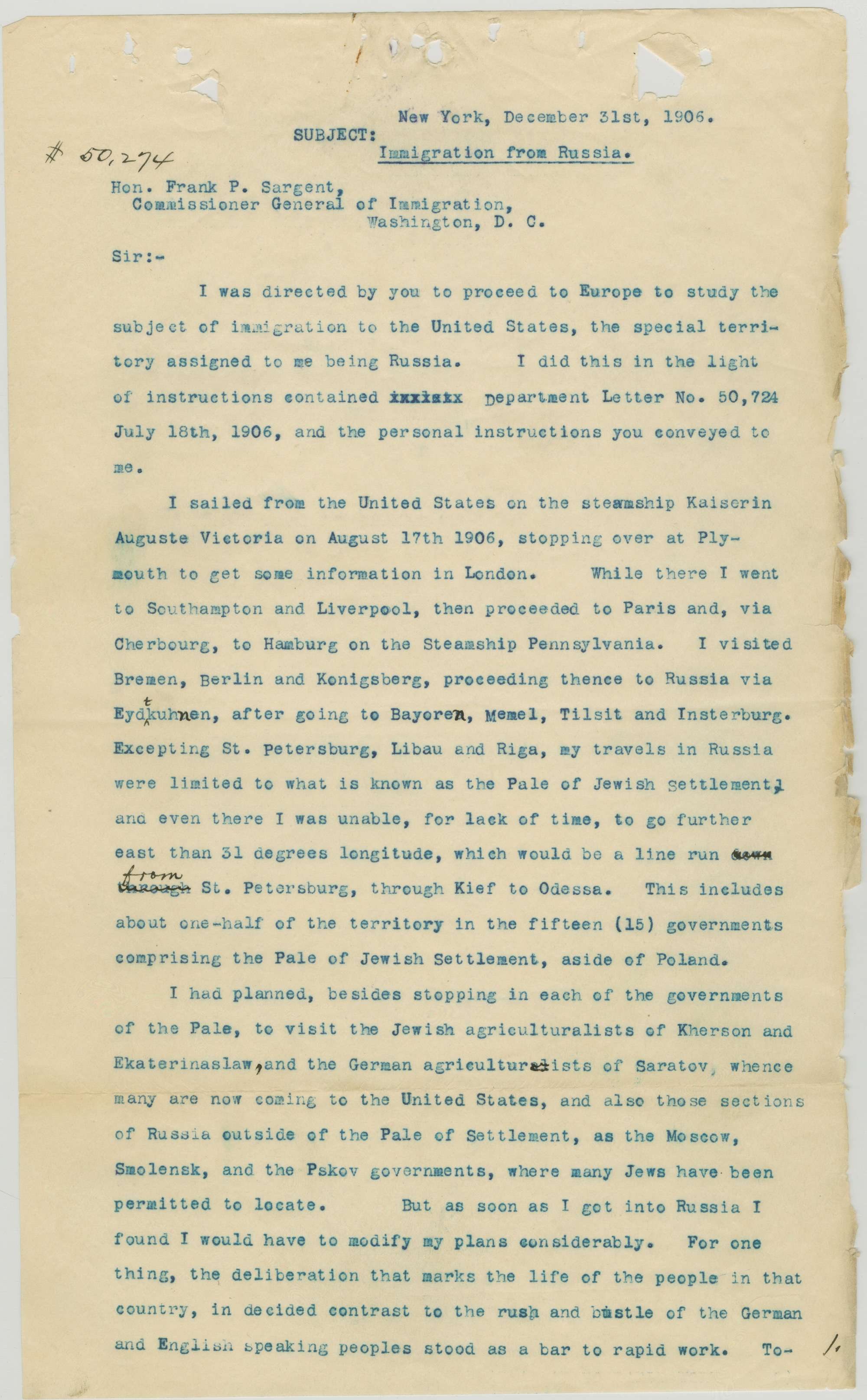

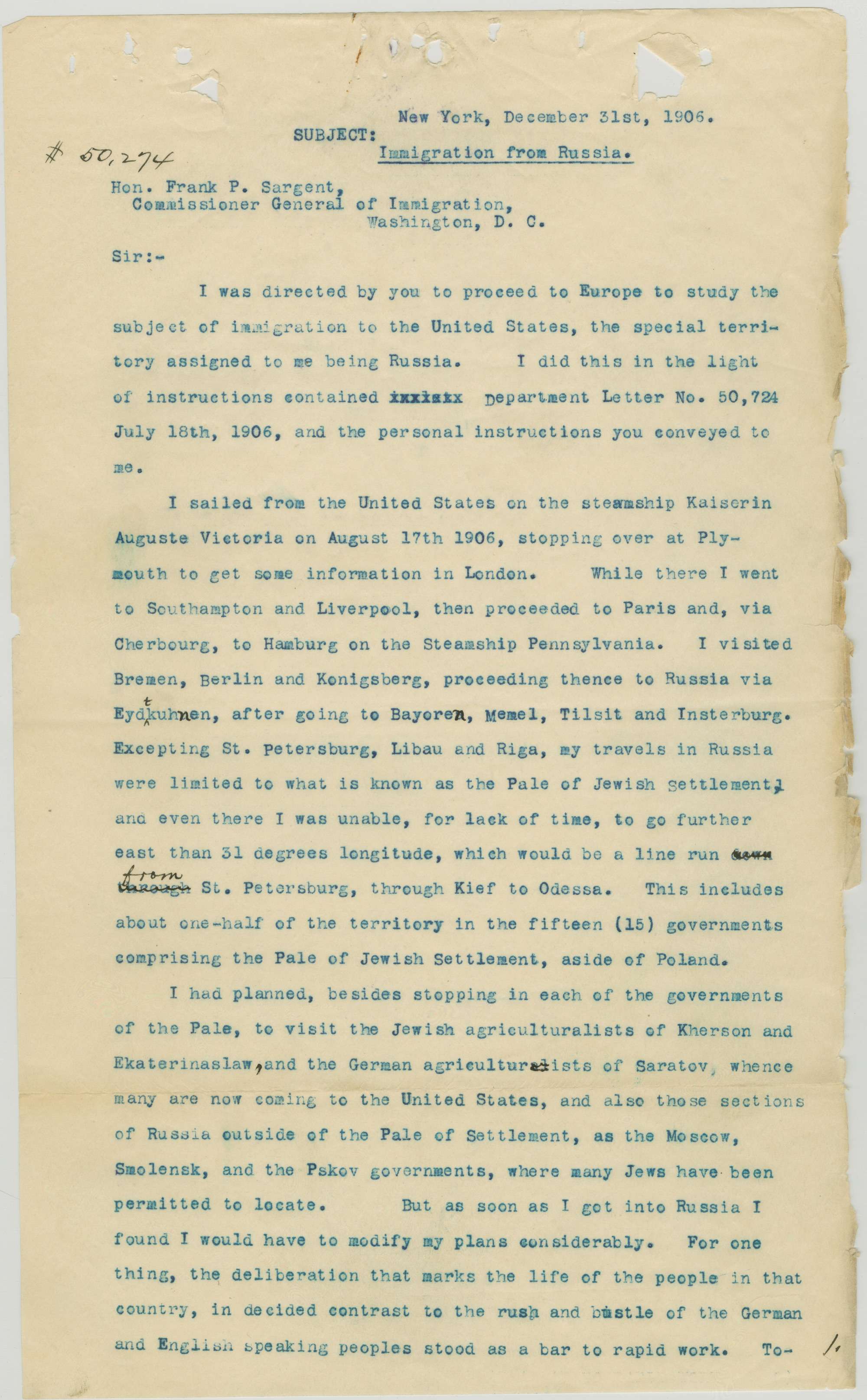

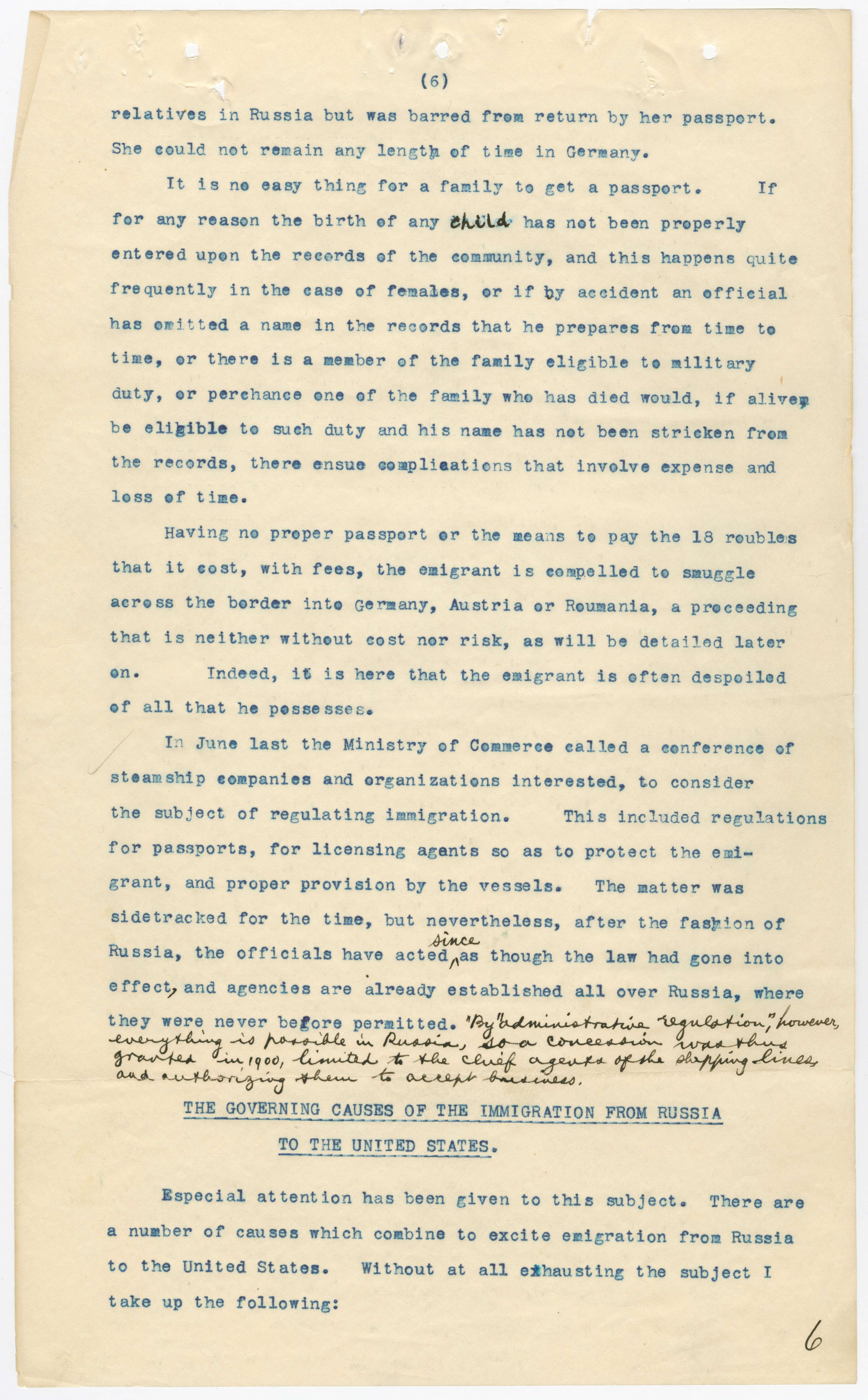

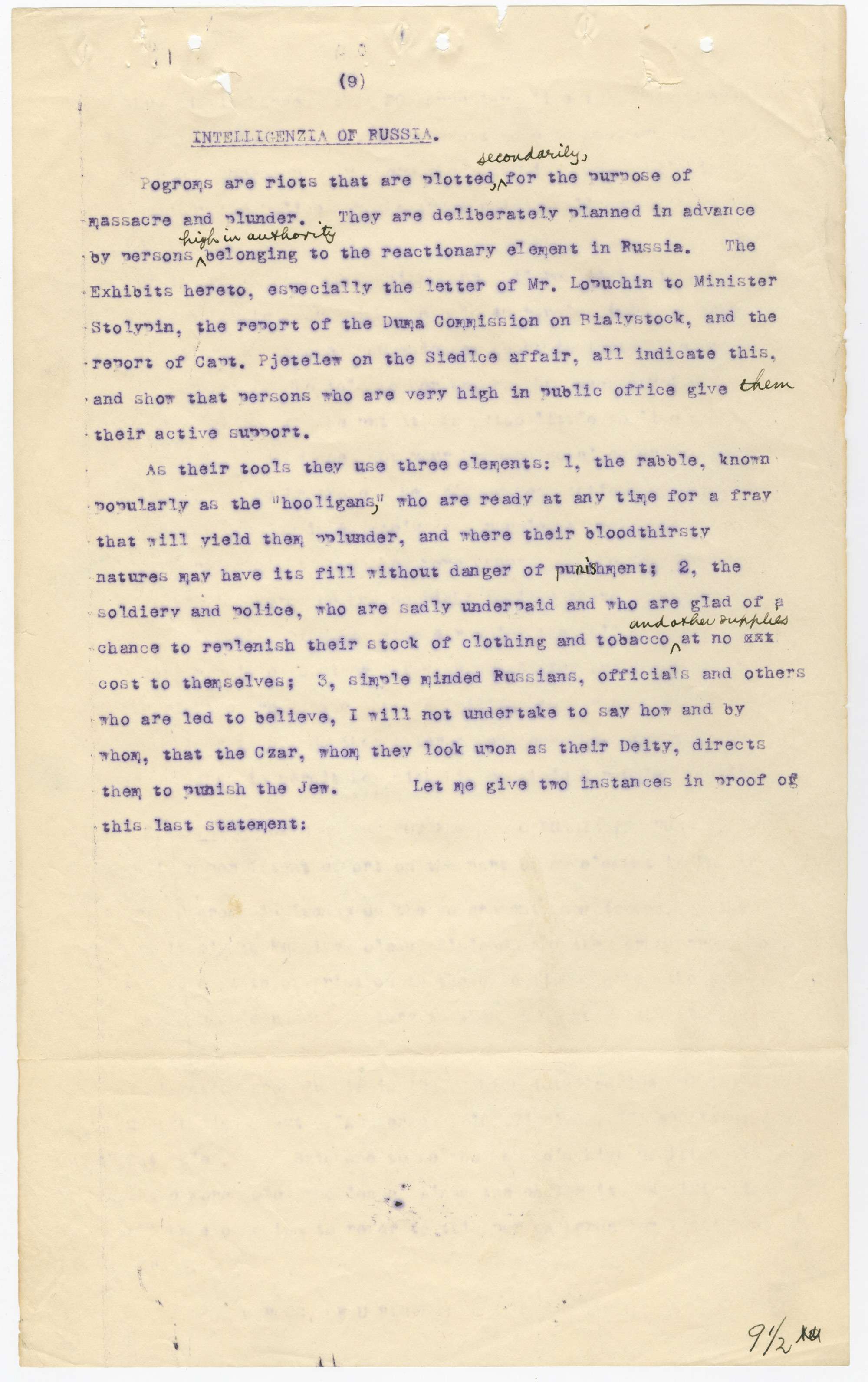

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

1906 - 1907

In 1906, the U.S. Government sent immigration inspector Philip Cowen on an undercover mission to the Pale of Settlement in Russia (St. Petersburg, Kief, and Odessa) to discover the cause of increased Jewish immigration from Russia to the United States. His findings revealed appalling and unremitting persecution of Russian Jews.

This is one section of Cowen’s report. It includes a summary of why he was sent to Russia, the political climate there, and what he sees as the causes of Jewish immigration from Russia to the United States:

Cowen tells of the Russian government’s persecution of Jews. Since 1882, the May Laws forced Jews out of their homes and required them all to live in the Pale of Settlement. Crowded into this small area of Russia, the Jews struggled to find jobs and pay rising rent prices.

Further sections of the report use poignant pictures and narration, to tell about difficult living conditions and economic hardship for Jews in Russia. Most tragic of all is Cowen’s description of the 637 pogroms—targeted attacks on Jews—committed against the Russian Jews. During these pogroms, entire Jewish cities were ransacked and destroyed while hundreds of Jews were brutally murdered. Cowen writes of these attacks through the stories of eyewitnesses who survived the pogroms. To escape such persecution, Jews sought to immigrate to America. But by accompanying Jewish immigrants on their journey to escape Russia, Cowen found out that Jewish persecution did not end with their departure. Jews were repeatedly charged double or triple the cost of passports and boat tickets to America.

This is one section of Cowen’s report. It includes a summary of why he was sent to Russia, the political climate there, and what he sees as the causes of Jewish immigration from Russia to the United States:

- laws against the Jews;

- efforts of the Government to Russianize Russia;

- the pogroms and Intelligenzia of Russia;

- the political, Social and Economic condition arising from the foregoing causes and the effort to change the present form of government;

- the expulsion of Russian Jews from Germany;

- the opening of direct passenger traffic between Russia and New York;

- the prosperity of the United States; the presence in America of a large Russo-Jewish population; and

- various other causes.

Cowen tells of the Russian government’s persecution of Jews. Since 1882, the May Laws forced Jews out of their homes and required them all to live in the Pale of Settlement. Crowded into this small area of Russia, the Jews struggled to find jobs and pay rising rent prices.

Further sections of the report use poignant pictures and narration, to tell about difficult living conditions and economic hardship for Jews in Russia. Most tragic of all is Cowen’s description of the 637 pogroms—targeted attacks on Jews—committed against the Russian Jews. During these pogroms, entire Jewish cities were ransacked and destroyed while hundreds of Jews were brutally murdered. Cowen writes of these attacks through the stories of eyewitnesses who survived the pogroms. To escape such persecution, Jews sought to immigrate to America. But by accompanying Jewish immigrants on their journey to escape Russia, Cowen found out that Jewish persecution did not end with their departure. Jews were repeatedly charged double or triple the cost of passports and boat tickets to America.

Transcript

New York, December 31st, 1906.SUBJECT:

Immigration from Russia.

[handwritten #50,274]

Hon. Frank P. Sargent,

Commissioner General of Immigration,

Washington, D. C.

Sir:-

I was directed by you to proceed to Europe to study the subject of immigration to the United States, the special territory assigned to me being Russia. I did this in light of instructions contained xxxxxxx Department Letter No. 50,724 July 18th, 1906, and the personal instructions you conveyed to me.

I sailed from the United States on the steamship Kaiserin Auguste Victoria on August 17th 1906, stopping over at Plymouth to get some information in London. While there I went to Southhampton and Liverpool, then proceeded to Paris and, via Cherbourg, to Hamburg on the Steamship Pennsylvania. I visited Bremen, Berlin and Konigsberg, proceeding thence to Russia via Eydtkuhnen, after going to Bayoren, Memel, Tilsit and Insterburg. Excepting St. Petersburg, Libau and Riga, my travels in Russia were limited to what is known as the Pale of Jewish Settlement, and even there I was unable, for lack of time, to go further east than 31 degrees longitude, which would be a line run down through [crossed out and replaced with from, handwritten] St. Petersburg, through Kief to Odessa. This includes about one-half of the territory in the fifteen (15) governments comprising the Pale of Jewish Settlement, aside of Poland.

I had planned, besides stopping in each of the governments of the Pale, to visit the Jewish agriculturalists of Kherson and Ekaterinaslaw, and the German agriculturalists of Saratov, whence many are now coming to the United States, and also those sections of Russia outside of the Pale of Settlement, as the Moscow, Smolensk, and the Pskov governments, where many Jews have been permitted to locate. But as soon as I got into Russia I found I would have to modify my plans considerably. For one thing, the deliberation that marks the life of the people in that country, in decided contrast to the rush and bustle of the German and English speaking peoples stood as a bar to rapid work. To-

1 [handwritten]

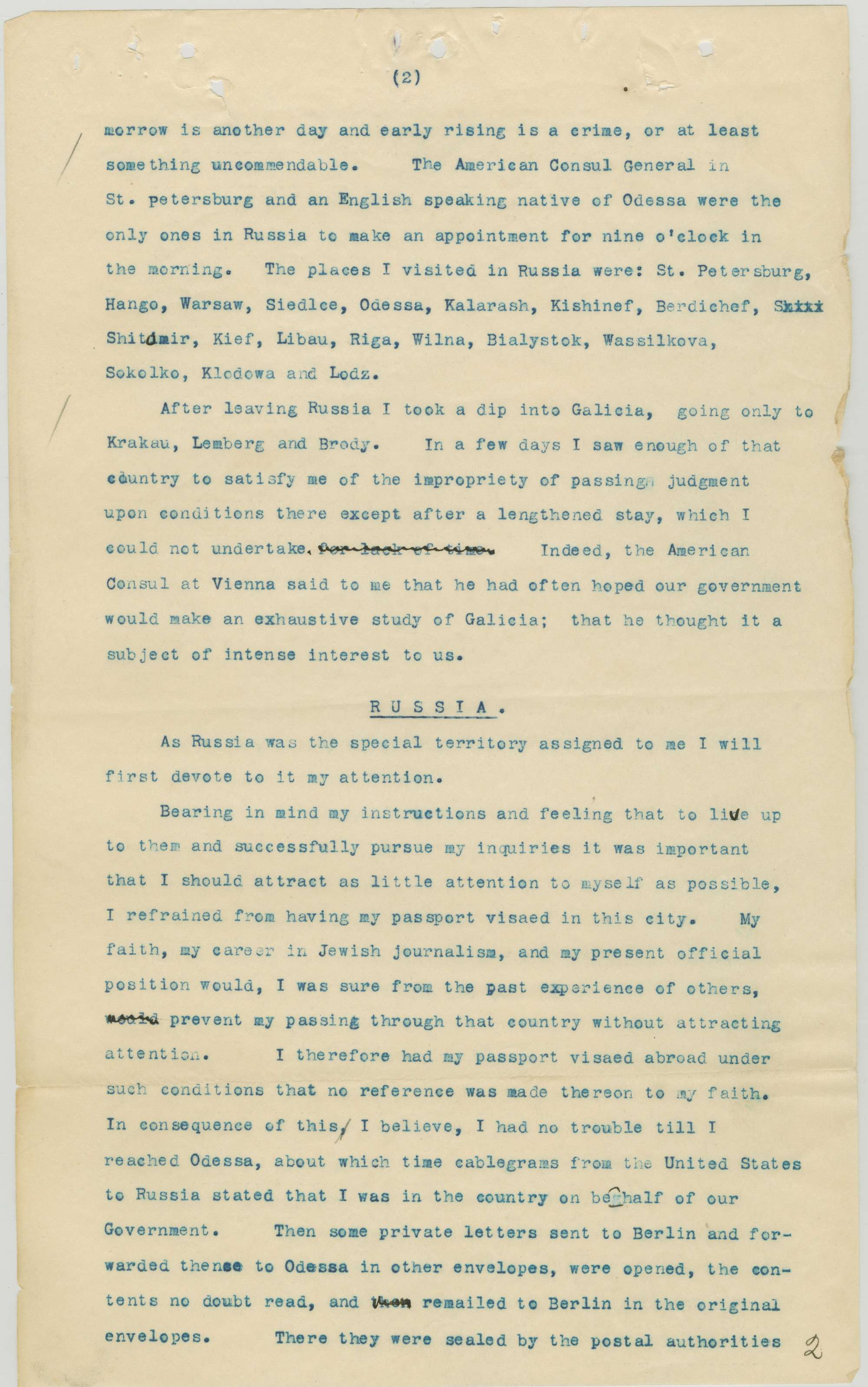

(2)

morrow is another day and early rising is a crime, or at least something uncommendable. The American Consul General in St. Petersburg and an English speaking native of Odessa were the only ones in Russia to make an appointment for nine o'clock in the morning. The places I visited in Russia were: St. Petersburg, Hango, Warsaw, Siedlce, Odessa, Kalarash, Kishinef, Berdichef, Shitdmir, Kief, Libau, Riga, Wilna, Bialystok, Wassilkova, Sokolko, Klodowa and Lodz.

After leaving Russia I took a dip into Galicia, going only to Krakau, Lemberg and Brody. In a few days I saw enogh of that country to satisfy me of the impropriety of passing judgment upon conditions there except after a lengthened stay, which I could not undertake. for lack of time [crossed out "for lack of time"] Indeed, the American Consul at Vienna said to me that he had often hoped our government would make an exhaustive study of Galicia; that he thought it a subject of intense interest to us.

RUSSIA. [Underlined]

As Russia was the special territory assigned to me I will first devote to it my attention.

Bearing in mind my instructions and feeling that to live up to them and successfully pursue my inquiries it was important that I should attract as little attention to myself as possible, I refrained from having my passport visaed in this city My faith, my career in Jewish journalism, and my present official position would, I was sure from the past experience of others, would [crossed out] prevent my passing through that country without attracting attention. I therefore had my passport visaed abroad under such conditions that no reference was made thereon to my faith. In consequence of this I believe, I had no trouble till I reached Odessa, about which time cablegrams from the United States to Russia stated that I was in the country on behalf of our Government. Then some private letters sent to Berlin and forwarded thence to Odessa in other envelopes, were opened, the contents no doubt read, and then [crossed out] remailed to Berlin in the original envelopes. There they were sealed by the postal authorities

2 [handwritten]

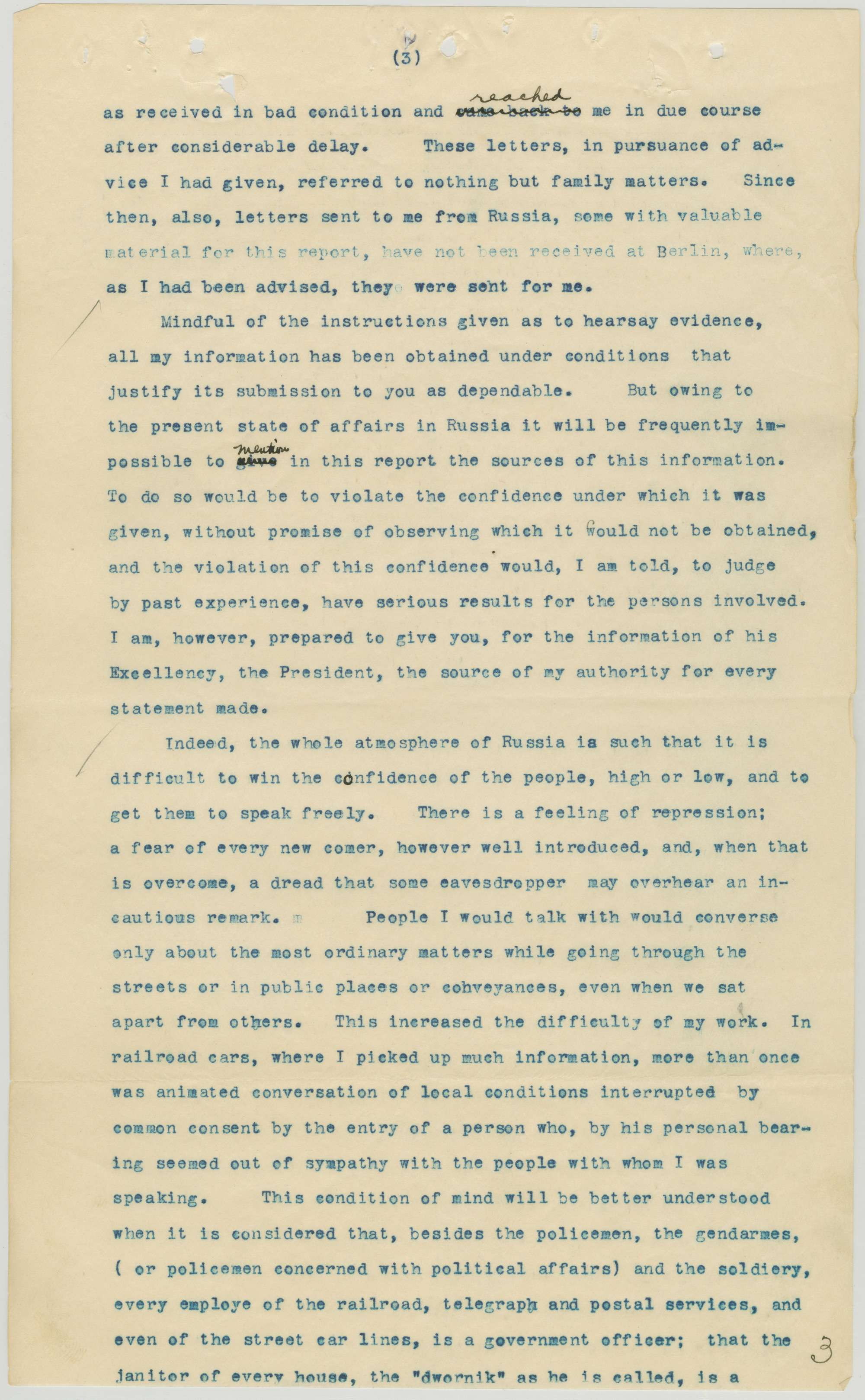

(3)

as received in bad condition and reached me in due course after considerable delay. These letters, in pursuance of advice I had given, referred to nothing but family matters. Since then, also, letters sent to me from Russia, some with valuable material for this report, have not been received at Berlin, where, as I had been advised, they were sent for me.

Mindful of the instructions given as to hearsay evidence, all my information has been obtained under conditions that justify its submission to you as dependable. But owing to the present state of affairs in Russia it will be frequently impossible to give [crossed out] mention in this report the sources of this information. To do so would be to violate the confidence under which it was given, without promise of observing which it could not be obtained, and the violation of this confidence would, I am told, to judge by past experience, have serious results for the persons involved. I am, however, prepared to give you, for the information of his Excellency, the President, the source of my authority for every statement made.

Indeed, the whole atmosphere of Russia is such that it is difficult to win the confidence of the people, high or low, and to get them to speak freely. There is a feeling of repression; a fear of every new comer, however well introduced, and, when that is overcome, a dread that some eavesdropper may overhear an incautious remark. People I would talk with would converse only about the most ordinary matters while going through the streets or in public places or conveyances, even when we sat apart from others. This increased the difficulty of my work. In railroad cars, where I pickup up much information, more than once was animated conversation of local conditions interrupted by common consent by the entry of a person who, by his personal bearing seemed out of sympathy with the people with whom I was speaking. This condition of mind will be better understood when it is considered that, besides the policemen, the gendarmes, (or policemen concerned with political affairs) and the soldiery, every employe of the railroad, telegraph and postal services, and even of the street car lines, is a government officer; that the janitor of every house, the "dwornik" as he is called, is a

3 [handwritten]

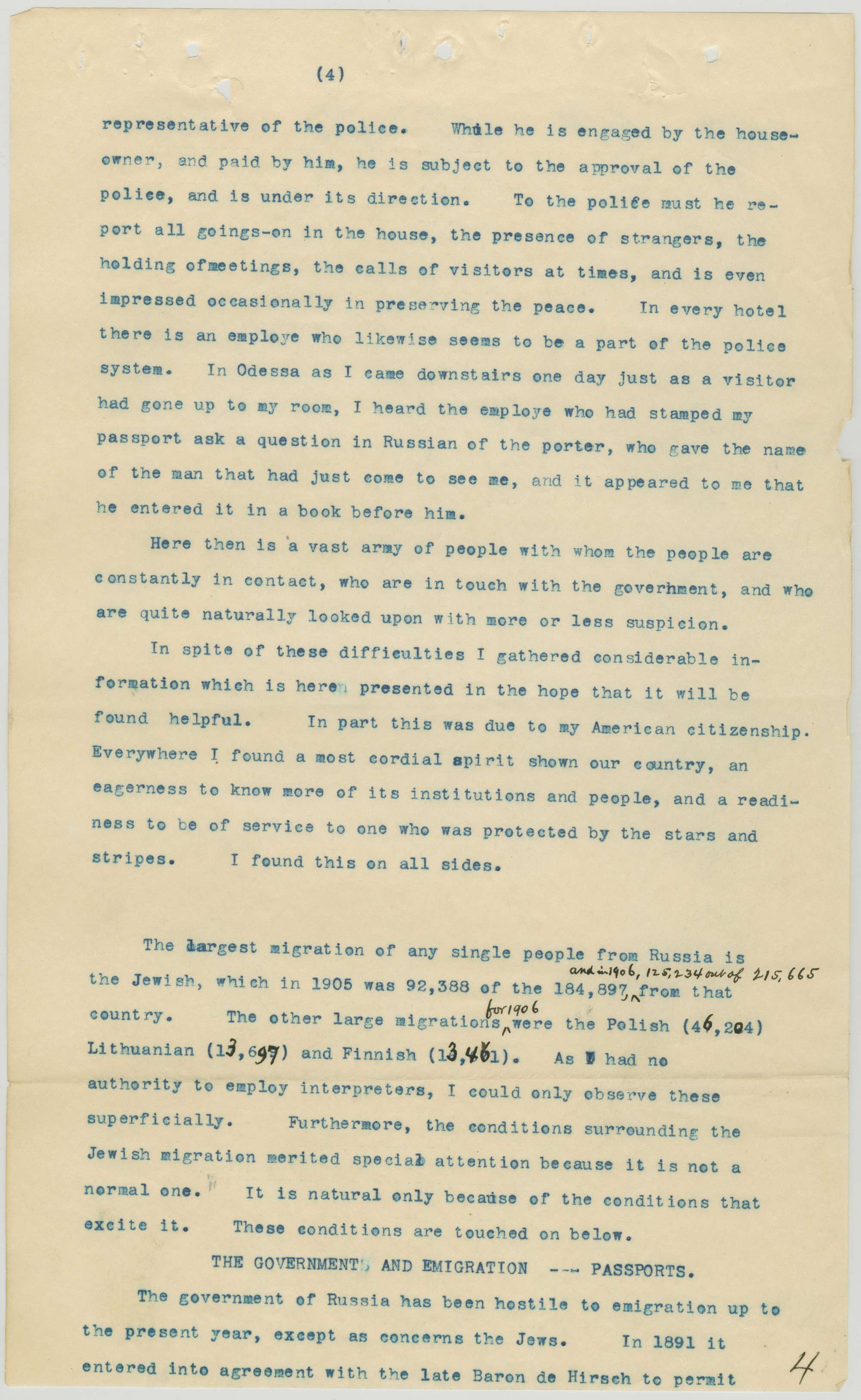

(4)

representative of the police. While he is engaged by the house-owner, and paid by him, he is subject to the approval of the police, and is under its direction. To the police must he report all goings-on in the house, the presence of strangers, the holding of meetings, the calls of visitors at times, and is even impressed occasionally in preserving the peace. In every hotel there is an employe who likewise seems to be a part of the police system. In Odessa as i came downstairs one day just as a visitor had gone up to my room, I heard an employe who had stamped my passport ask a question in Russian of the porter, who gave the name of the man that had just come to see me, and it appeared to me that he entered it in a book before him.

Here then is a vast army of people with whom the people are constantly in contact, who are in touch with the government, and who are quite naturally looked upon with more or less suspicion.

In spite of these difficulties I gathered considerable information which is here presented in the hope that it will be found helpful. In part this was due to my American citizenship. Everywhere I found a most cordial spirit shown our country, an eagerness to know more of its institutions and people, and a readiness to be of service to one who was protected by the stars and stripes. I found this on all sides.

The largest migration of any single people from Russia is the Jewish, which in 1905 was 92,388 of the 184,897, [handwritten: and in 1906, 125,234 out of 215,665) from that country. The other large migrations for 1906, were the Polish (46,204) Lithuanian (13,697) and Finnish (13,461). As I had no authority to employ interpreters, I could only observe these superficially. Furthermore, the conditions surrounding the Jewish migration merited special attention because it is not a normal one. It is natural only because of the conditions that excite it. These conditions are touched on below.

THE GOVERNMENT AND EMMIGRATION ---PASSPORTS

The government of Russia has been hostile to emigration up to the present year, except as concerns the Jews. In 1891 it entered into agreement with the late Baron de Hirsch to permit

4 [handwritten]

(5)

the emigration of Jews under the direction of a central committee established by him at St. Petersburg, the purpose of Baron de Hirsch being to check the mad rush that followed the renewed enforcement of the May Laws of 1882. With this exception, the government, so far as I can see, has not been firnedly [crossed out] friendly to emigration, the laws providing for the punishment of those who would make propaganda therefor. Persons who were entitled to Governor's passports, that allowed passing out of the country, were, however, permitted to go, if military duty did not interfere. Those who could not obtain such passports found some difficulty in getting out. If they had a "mishansky passport," that allowed them to travel through Russia, they would often go to Finland, whose independent laws were not so strict as to passports. Thence they would sail from Hango via Germany or England to South Africa, South America, Canada or the United States. When I was Hango in October this freedom of passport regulation still prevailed, but I was informed later that, on the urgent representations of the the Ministry of Russia, the Finland authorities agreed to require a full passport -- a governor's passport -- of every intending immigrant. It was currently believed, however, that this was but a temporary condition.

The governor's passport costs, with fees, about 18 roubles. There is another form that permits passage from the country, which is given under certain conditions, which may be called an emigrant's passport, This is given without charge, except as to fees, but only on promise that those getting it will not again return to Russia. This works a serious hardship when a family having it, or any of its members, are deported from the United States. Then they become outcasts. I saw some people so situated in Berlin and Kenigsberg. Where they were "poor physique," the Jewish Committee sent them to Argentine, and in one case where a wife was deported for trachoma, her children being with her husband, she was held and her husband and children advised to go to Argentine and establish a home there, when the wife and mother would be forwarded. Other cases presented serious hardships, as where a girl was returned with a weak intellect, who had

5 [handwritten]

(6)

relatives in Russia but was barred from return by her passport. She could not remain any length of time in Germany.

It is no easy thing for a family to get a passport. If for any reason the birth of any child [handwritten] has not been properly entered upon the records of the community, and this happens quite frequently in the case of females, or fi by accident an official has omitted a name in the records that he prepares from time to time, or there is a member of the family eligible to military duty, or perchance one of the family who had died would, if alive be eligible to such duty and his name has not been stricken from the records, there ensue complications that involve expense and loss of time.

Having no proper passport or the means to pay the 18 roubles that it cost, with fees, the emigrant is compelled to smuggle across the border into Germany, Austria or Roumania, a proceeding that is neither without cost nor risk, as will be detailed later on. Indeed, it is here that the emigrant is often despoiled of all that he possesses.

In June last the Ministry of Commerce called a conference of steamship companies and organizations interested, to consider the subject of regulating immigration. This included regulations for passports, for licensing agents so as to protect the emigrant, and proper provision by the vessels. The matter was sidetracked for the time, but nevertheless, after the fashion of Russia, the officials have acted [handwritten: since] as though the law had gone into effect, and agencies are already established all over Russia, where they were never before permitted. [handwritten] By "administrative regulation", however, everything is possible in Russia, so a concession was thus granted in 1900, limited to the chief agents of the shipping lines, and authorizing them to accept business.

THE GOVERNING CAUSES OF THE IMMIGRATION FROM RUSSIA TO THE UNITED STATES [underlined]

Especial attention has been given to this subject. There are a number of causes which combine to excite emigration from Russia to the United States. Without at all exhausting the subject I take up the following:

6 [handwritten]

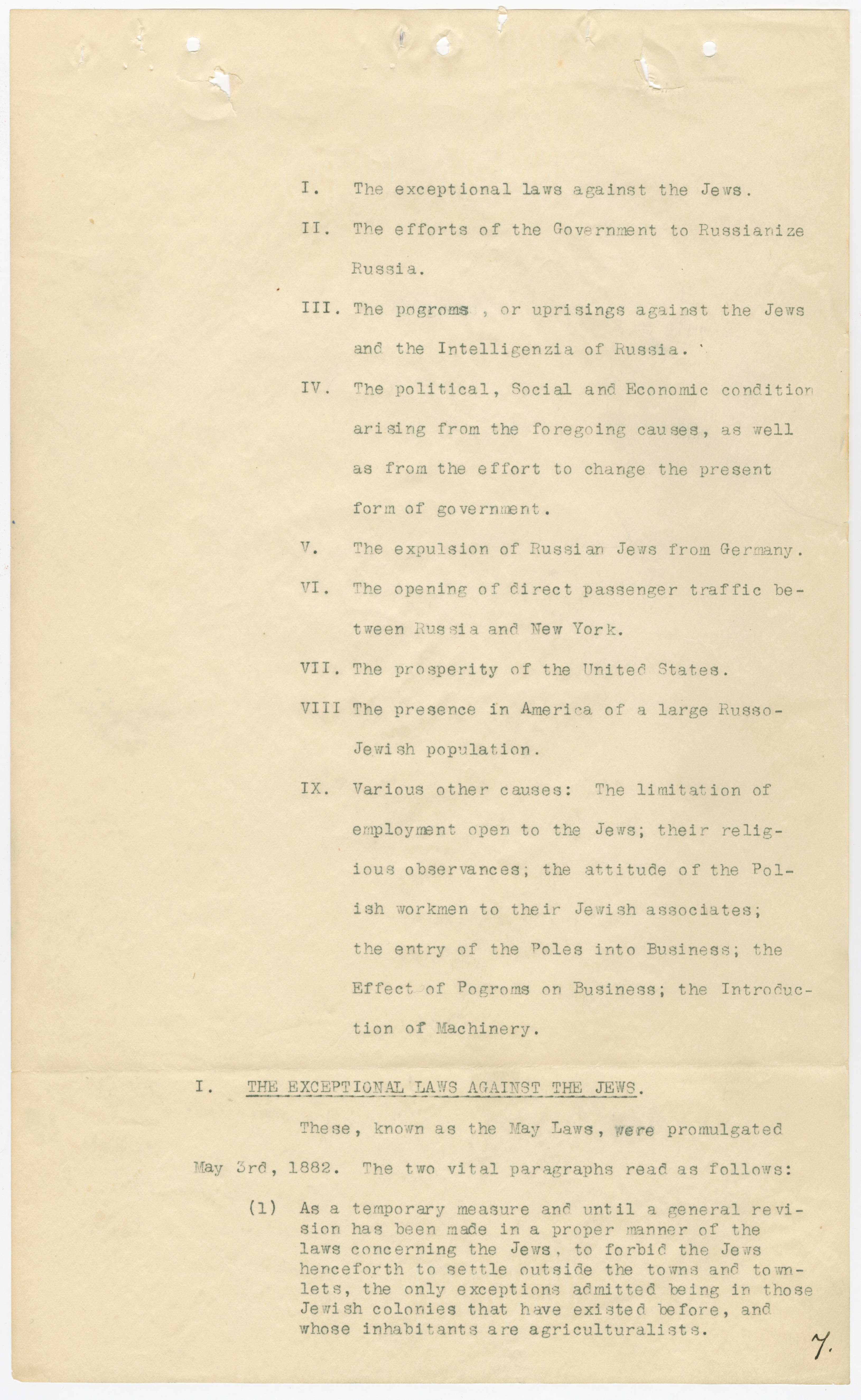

I. The exceptional laws against the Jews.

II. The efforts of the Government to Russianize Russia.

III. The pogroms, or uprisings against the Jews and the Intelligenzia of Russia.

IV. The political, Social and Economic condition arising from the foregoing causes, as well as from the effort to change the present form of government.

V. The expulsion of Russian Jews from Germany.

VI. The opening of direct passenger traffic between Russia and New York.

VII. The prosperity of the United States.

VIII. The presence in America of a large Russo-Jewish population.

IX. Various other causes: The limitation of employment open to the Jews; their religious observances; the attitude of the Polish workmen to their Jewish associates; the entry of the Poles into Business; the Effect of Pogroms on Business; the Introduction of machinery.

1. THE EXCEPTIONAL LAWS AGAINST THE JEWS [underlined]

These, known as the May Laws, were promulgated May 3rd, 1882. The two vital paragraphs read as follows:

(1) As a temporary measure and until a general revision has been made in a proper manner of the laws concerning the Jews, to forbid the Jews henceforth to settle outside the town and townlets, the only exceptions admitted being in those Jewish colonies that have existed before, and whose inhabitants are agriculturalists.

7 [handwritten]

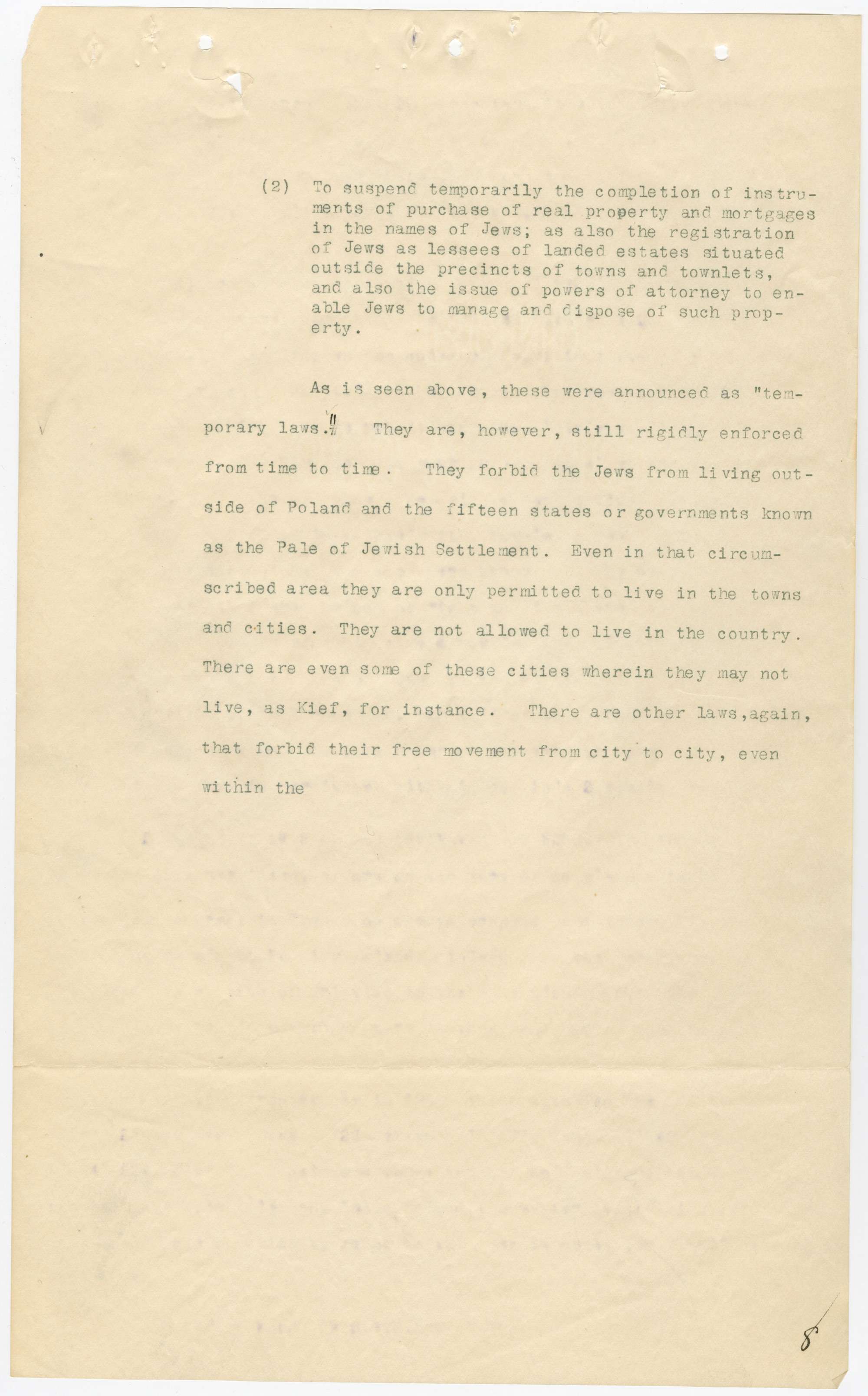

(2) To suspend temporarily the completion of instruments of purchase of real property and mortgages in the names of Jews; as also the registration of Jews as lessees of landed estates situated outside the precincts of towns and townlets, and also the issue of powers of attorney to enable Jews to manage and dispose of such property.

As is seen above, these were announced as "temporary laws." They are, however, still rigidly enforced from time to time. They forbid the Jews from living outside of Poland and the fifteen states or governments known as the Pale of the Jewish Settlement. Even in that circumscribed area they are only permitted to live in the towns and cities. They are not allowed to live in the country. There are even some of these cities wherein they may not live, as Kief, for instance. There are other laws, again, that forbid their free movement from city to city, even within the

8 [handwritten]

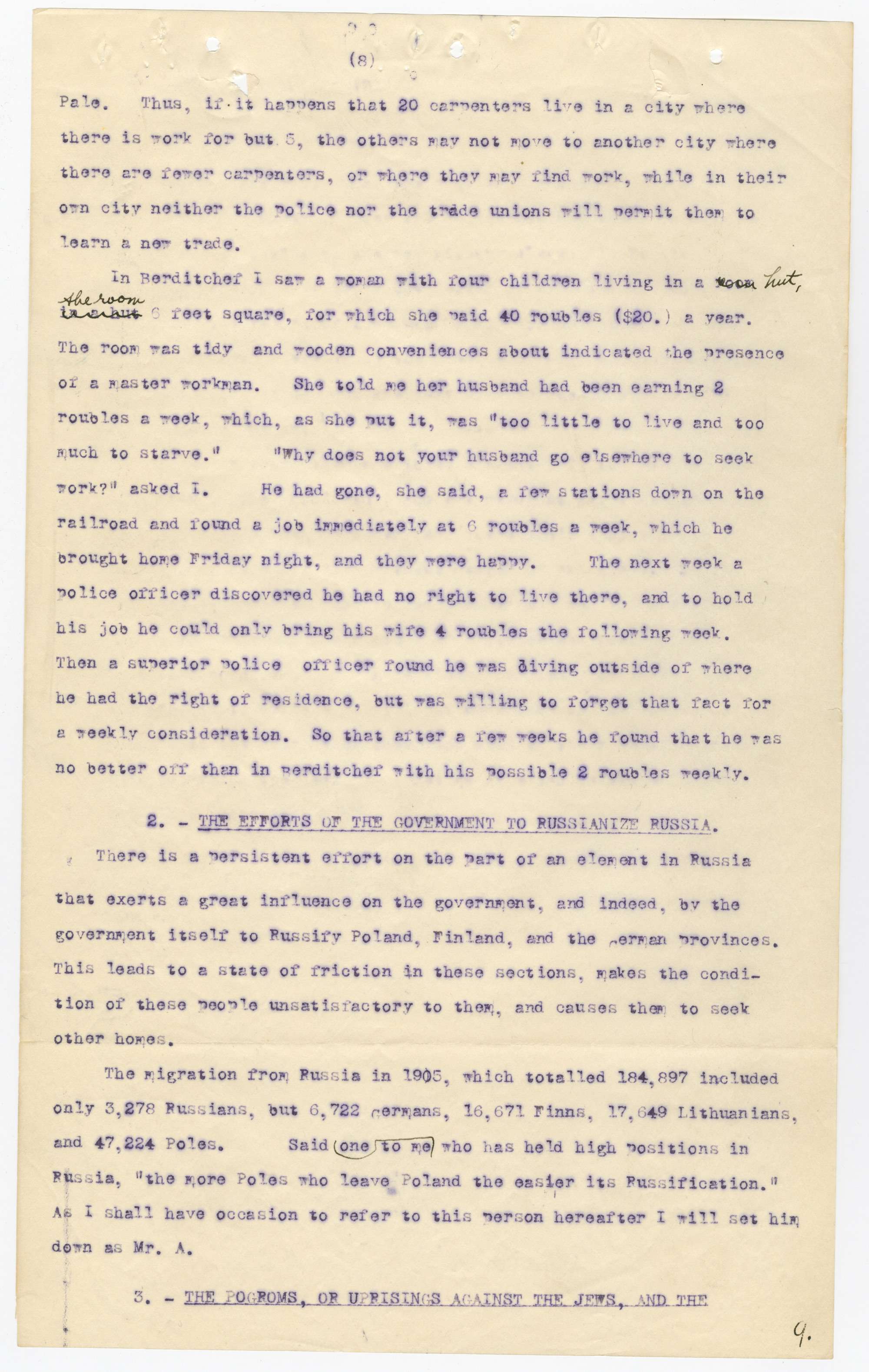

(8)

Pale. Thus, if it happens that 20 carpenters live in a city where there is work for but 5, the others may not move to another city where there are fewer carpenters, or where they may find work, while in their own city neither the police nor the trade unions will permit them to learn a new trade.

In Berditchef I saw a woman with four children living in a [crossed out, “room in a hut”], hut the room [handwritten] 6 feet square, for which she paid 40 roubles (20). a year. The room was tidy and wooden conveniences about indicated the presence of a master workman. She told me her husband had been earning 2 roubles a week, which, as she put it, was "too little to live and too much to starve." "Why does not your husband go elsewhere to seek work?" asked I. He had gone, she said, a few stations down on the railroad and found a job immediately at 6 roubles a week, which he brought home Friday night, and they were happy. The next week a police officer discovered he had no right to live there, and to hold his job h could only bring his wife 4 roubles the following week. Then a superior police officer found he was living outside of where he had the right of residence, but was willing to forget that fact for a weekly consideration. So that after a few weeks he found that he was no better off than in Berditchef with his possible 2 roubles weekly.

2. THE EFFORTS OF THE GOVERNMENT TO RUSSIANIZE RUSSIA. [underlined]

There is a persistent effort on the part of an element in Russia that exerts a great influence on the government, and indeed, by the government itself to Russify Poland, Finland, and the German provinces. This leads to a state of friction in these sections, makes the condition of these people unsatisfactory to them, and causes them to seek other homes.

The migration from Russia in 1905, which totalled 184,897 included only 3,278 Russians, but 6,722 Germans, 16, 671 Finns, 17, 649 Lithuanians, and 47,224 Poles. Said one to me, who had held high positions in Russia, "the more Poles who leave Poland the easier its Russification." As I shall have occasion to refer to this person hereafter I will set him down as Mr. A.

3. THE POGROMS, OR UPRISINGS AGAINST THE JEWS, AND THE [underlined]

9 [handwritten]

INTELLIGENZIA OF RUSSIA. [underlined]

Pogroms are riots that are plotted, [handwritten: secondarily], for the purpose of massacre and plunder. They are deliberately planned in advance by persons [handwritten: high in authority] belonging to the reactionary element in Russia. The exhibits hereto, especially the letter of Mr. Lopuchin to Minister Stolypin, the report of the Duma Commission on Bialvstock, and the report of Capt. Pjetelew on the Sied ice affair , all indicate this is and show that persons who are very high in public office [handwritten: them] their active support.

As their tools they use three: I, the rabble, known popularly as the "hooligans", who are ready at any time for a fray that will yield then plumber, and where their bloodthirsty natures may have its fill without danger of punishment 2, the soldiery and police who are sadly underpaid and who are glad of chance to replenish their stock of clothing and tobacco [handwritten: and other supplies] at no cost to themselves; 3, simple midned Russians, officials and others who are led to believe, I will not undertake to say how and by whom, that the Czar, whom thy look upon as their Deity, directs them to punish the Jew. Let me give two instances in proof of this last statement:

9 1/2 [handwritten]

This primary source comes from the Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

National Archives Identifier: 602984

Full Citation: Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9; 1906 - 1907; File No. 51411/056; Subject and Policy Files, 1893 - 1957; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/cowen-report, April 19, 2024]Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 1

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 2

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 3

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 4

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 5

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 6

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 7

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 8

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 9

Cowen Report - European Investigation Entry No. 9

Page 10

Document

Immigrants Arriving at the Immigration Station on Angel Island

ca. 1931

This undated photograph captures just a few of the millions of Asian immigrants to pass through Angel Island, in California’s San Francisco Bay. Now a National Historic Landmark and State Park, Angel Island served as a U.S. Immigration Station from 1910 until 1941. Although immigrants were usually detained here for a week or two in a housing compound for processing, some spent as long as two years for health reasons.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Public Health Service.

National Archives Identifier: 595673

Full Citation: Photograph 90-G-152-2038; Immigrants Arriving at the Immigration Station on Angel Island; ca. 1931; Public Health Service Historical Photograph File, 1880 - 1943; Records of the Public Health Service, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/arriving-angel-island, April 19, 2024]Immigrants Arriving at the Immigration Station on Angel Island

Page 1

Document

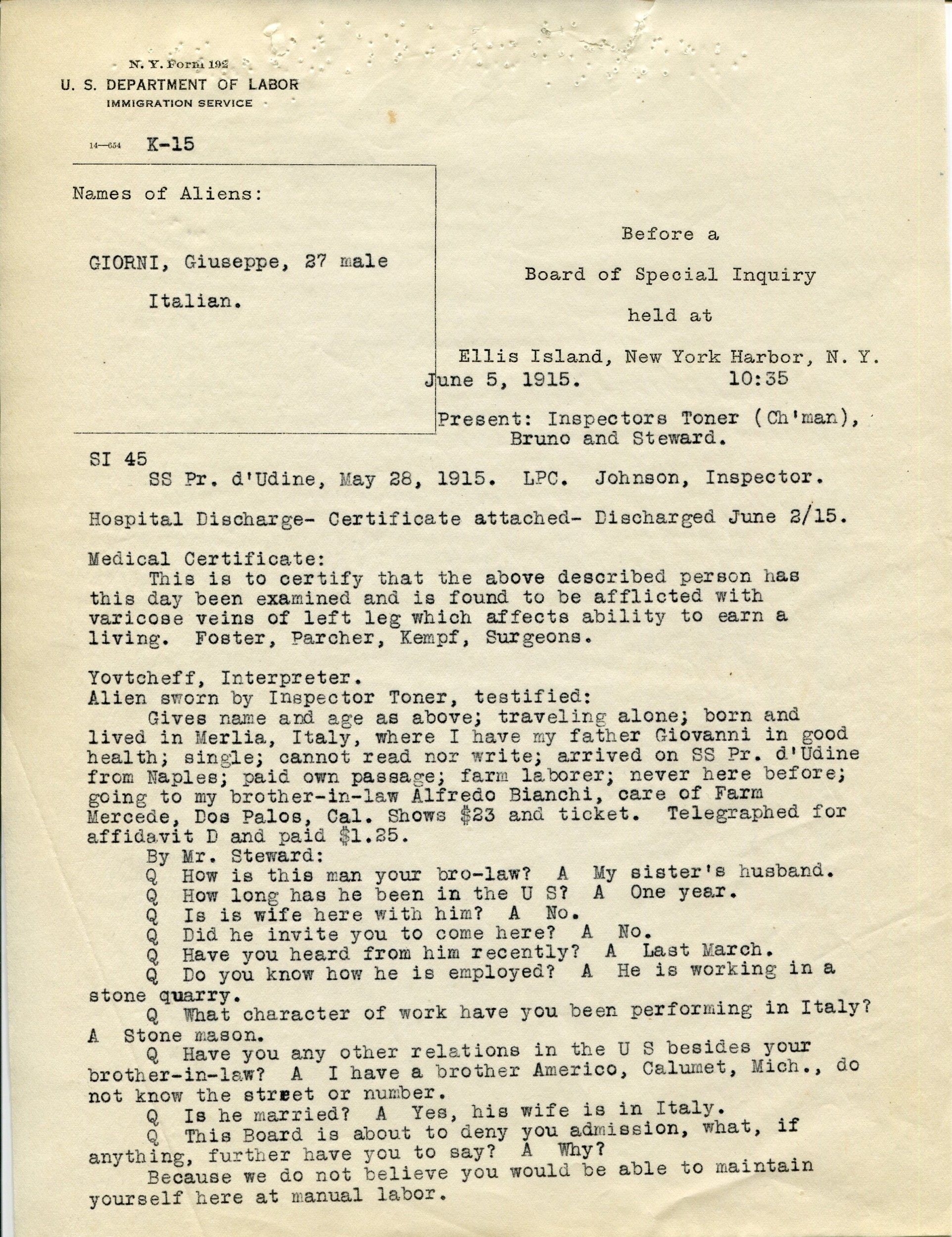

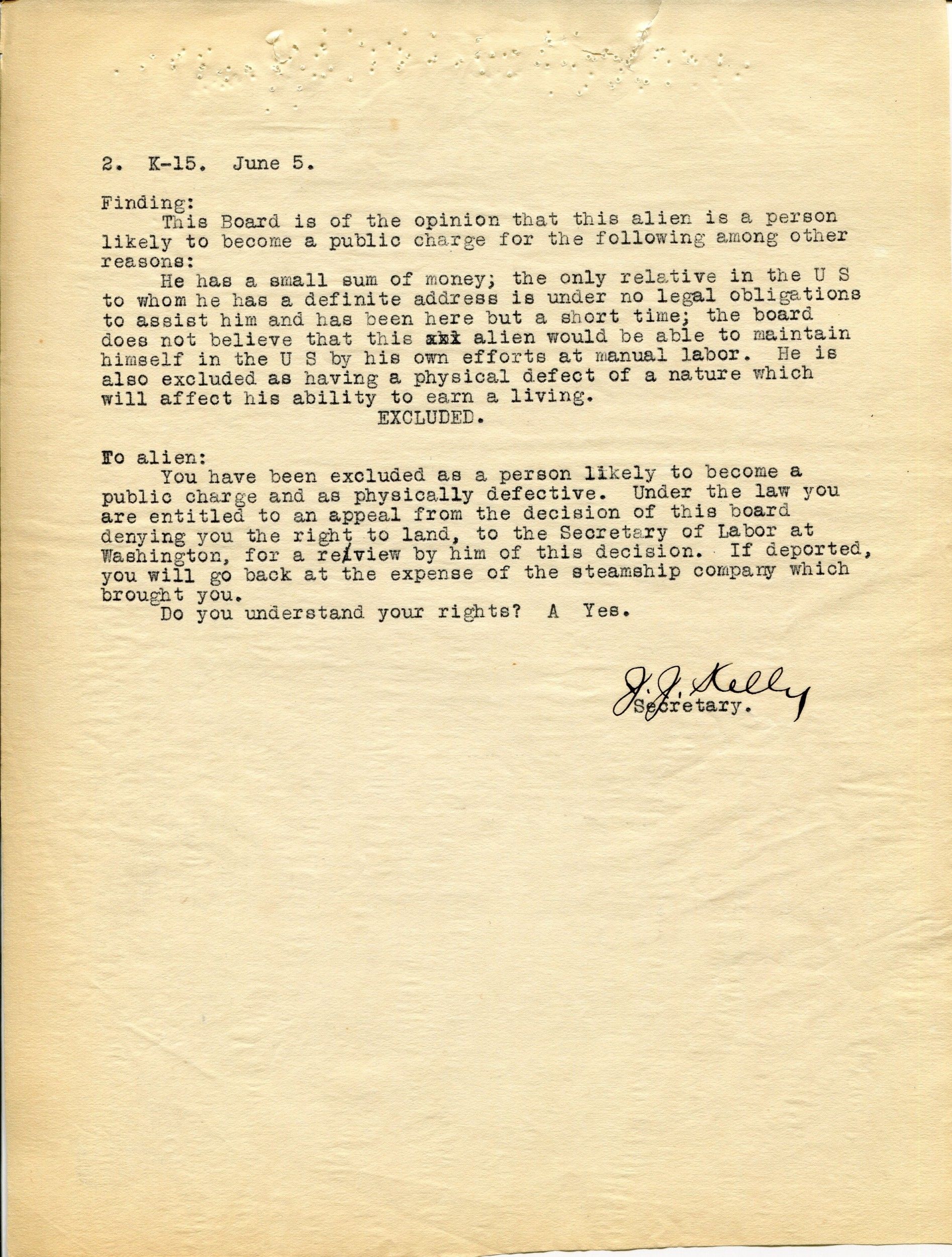

Report of Special Inquiry Held at Ellis Island Regarding Deportation of Italian Immigrants

6/5/1915

This document shows the interview and findings for the status of Giuseppe Giorni, a 27 year old male immigrant from Italy. The inquiry determined Giorni was to be deported based on his varicose veins and that he would likely become a public charge. It comes from a file about European war, German refugees, deportation of Italians, and alien deportations from 1914–1915.

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2014 Summer Workshop in Washington, DC.

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2014 Summer Workshop in Washington, DC.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

National Archives Identifier: 12013855

Full Citation: Report of Special Inquiry Held at Ellis Island Regarding Deportation of Italian Immigrants; 6/5/1915; 53584/39A; European War - German Refugees - Deportation of Italians - Alien Deportations; Subject and Policy Files, 1893 - 1957; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/special-inquiry-giorni, April 19, 2024]Report of Special Inquiry Held at Ellis Island Regarding Deportation of Italian Immigrants

Page 1

Report of Special Inquiry Held at Ellis Island Regarding Deportation of Italian Immigrants

Page 2

Document

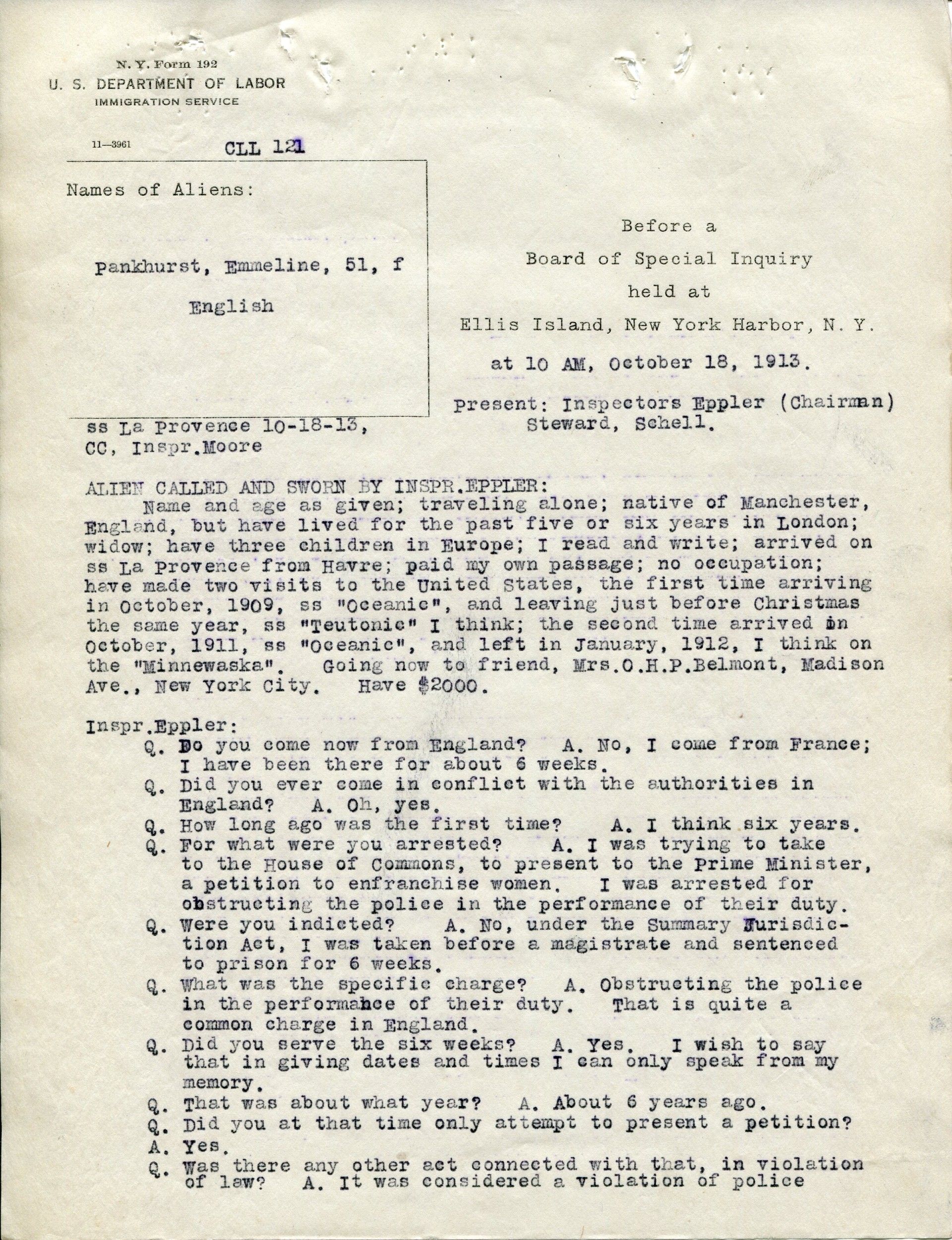

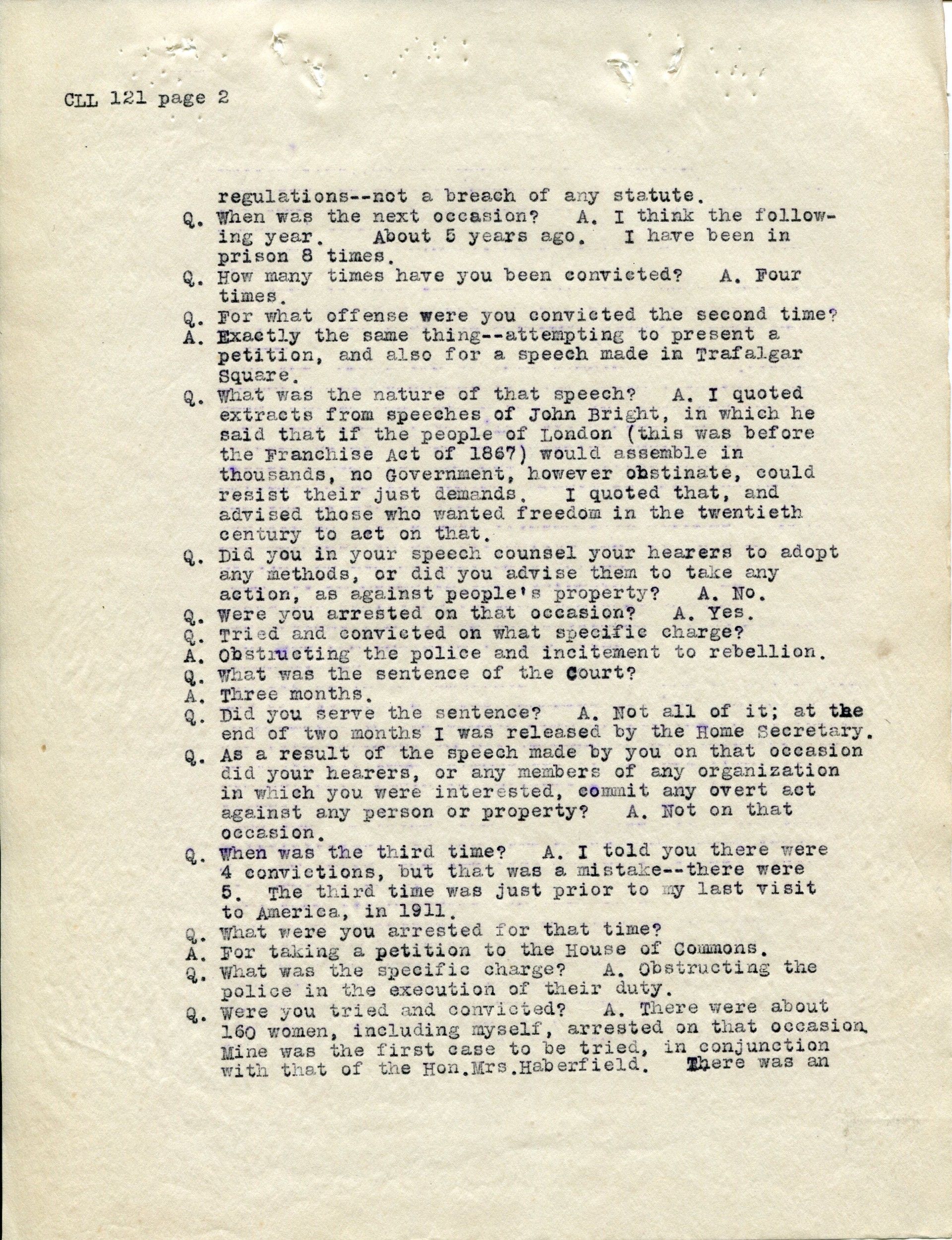

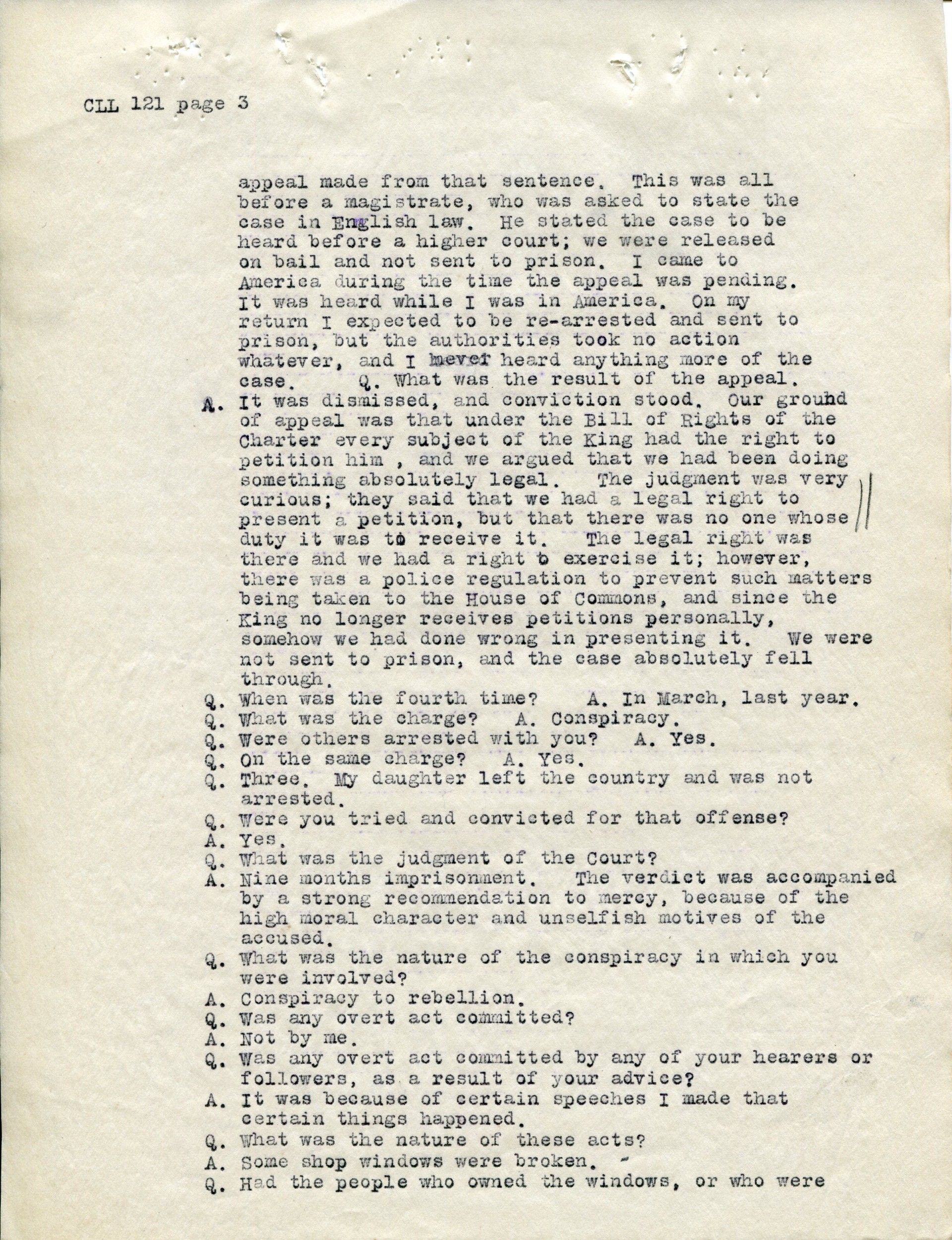

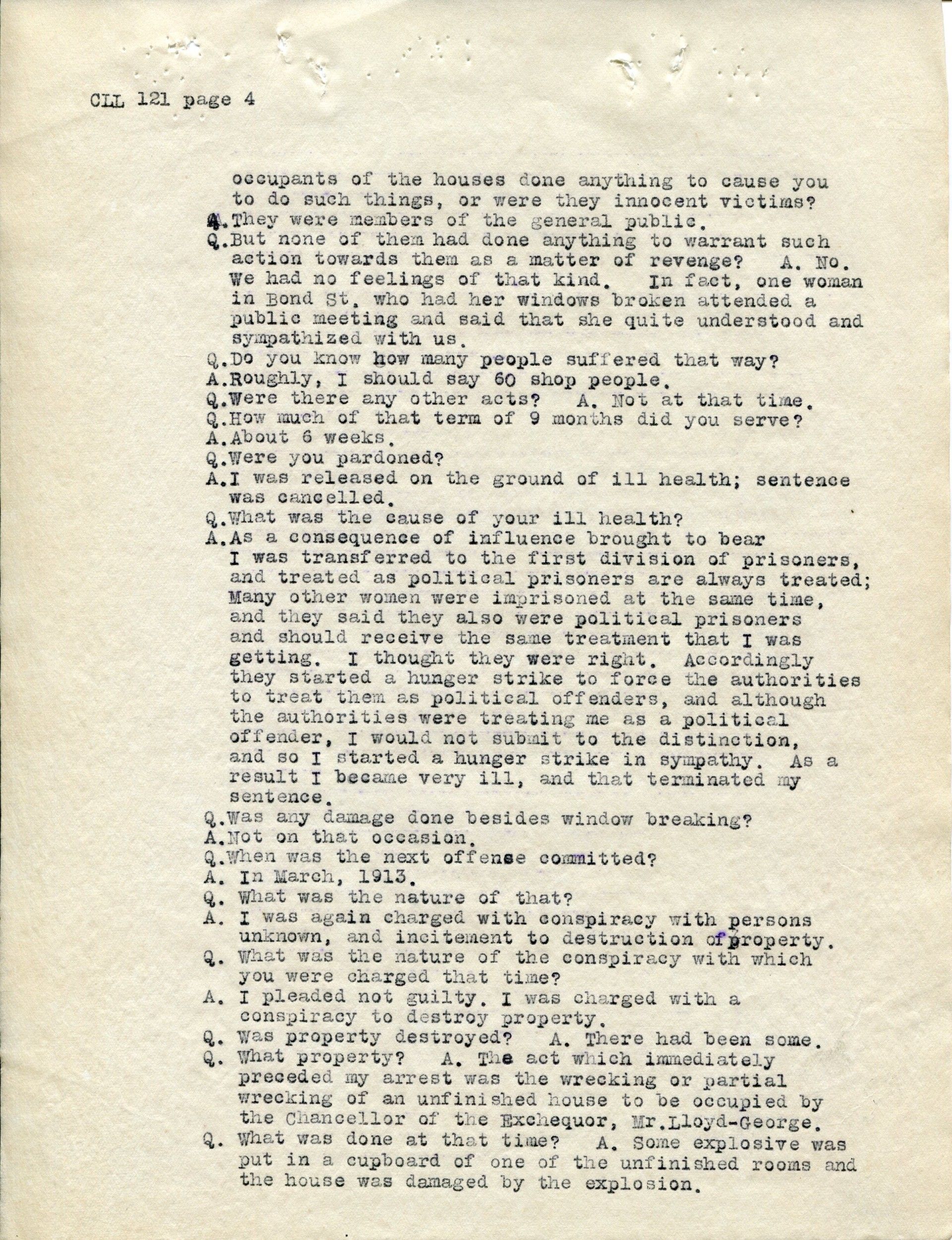

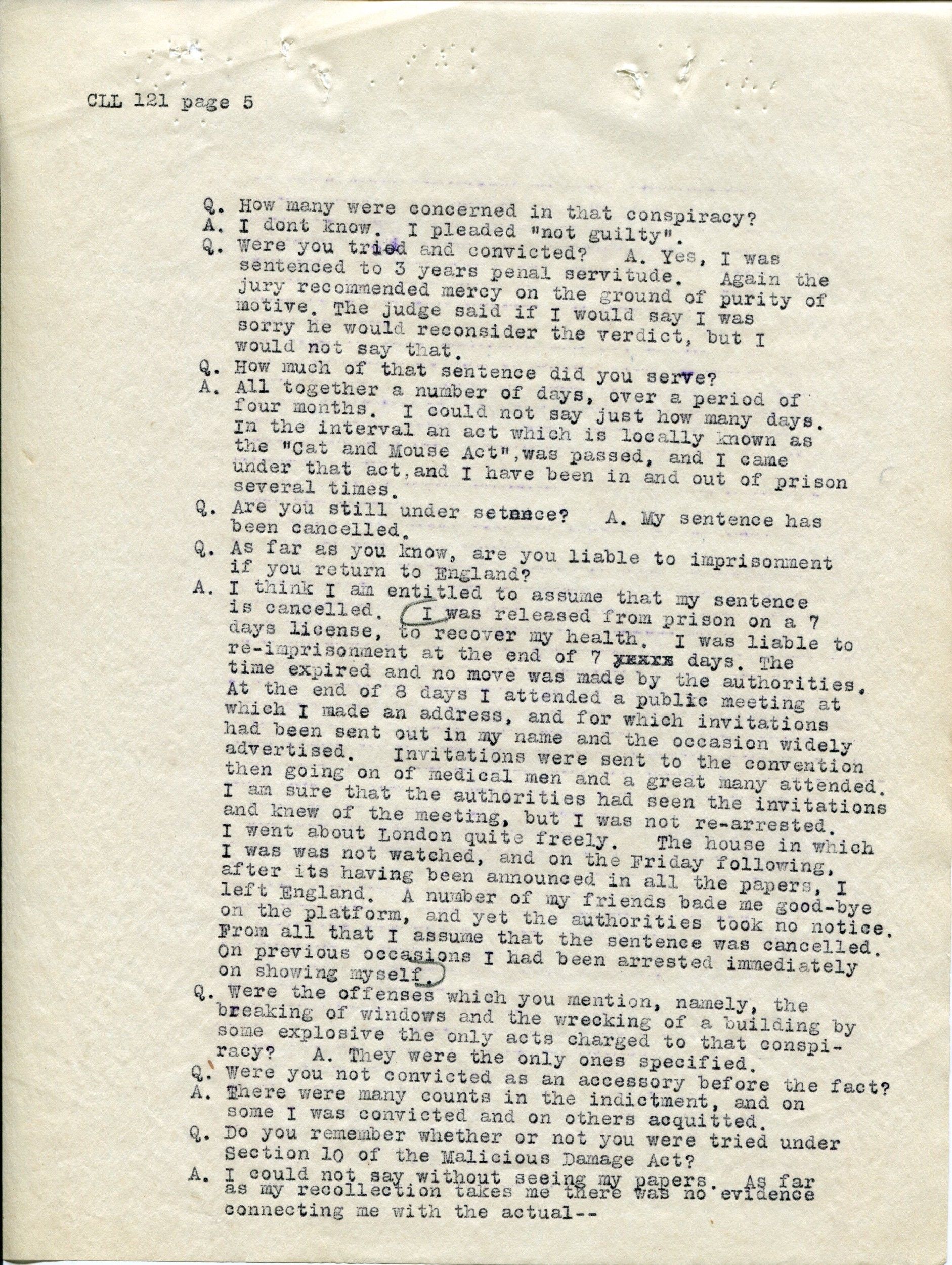

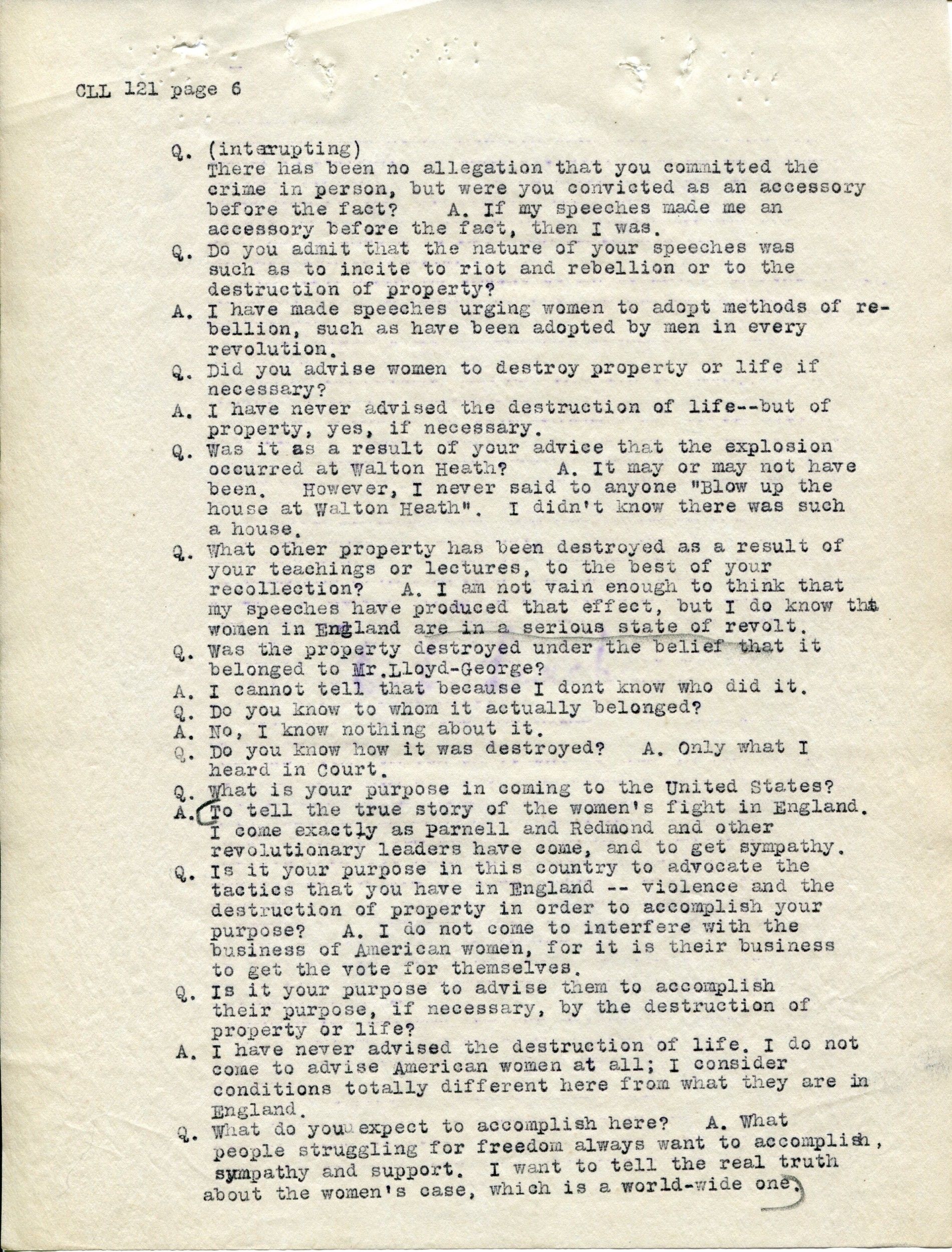

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

10/18/1913

This transcript recounts the questioning of Emmeline Pankhurst by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island. The Board's questions sought to determine whether Pankhurst should be deported or admitted into the United States.

The report provides details about Pankhurst's actions and criminal history in England. The Board of Inquiry decided to deport her as her actions involved "moral turpitude." It comes from an appeal of English suffragette Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst for admittance.

The report provides details about Pankhurst's actions and criminal history in England. The Board of Inquiry decided to deport her as her actions involved "moral turpitude." It comes from an appeal of English suffragette Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst for admittance.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

National Archives Identifier: 18503946

Full Citation: Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island; 10/18/1913; 51728/017; Appeal of Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst for admittance for visit, English Suffragette; Subject and Policy Files, 1893 - 1957; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/emmeline-pankhurst-questioning-ellis-island, April 19, 2024]Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 1

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 2

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 3

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 4

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 5

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 6

Transcript of Emmeline Pankhurst's Questioning by the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island

Page 7

Document

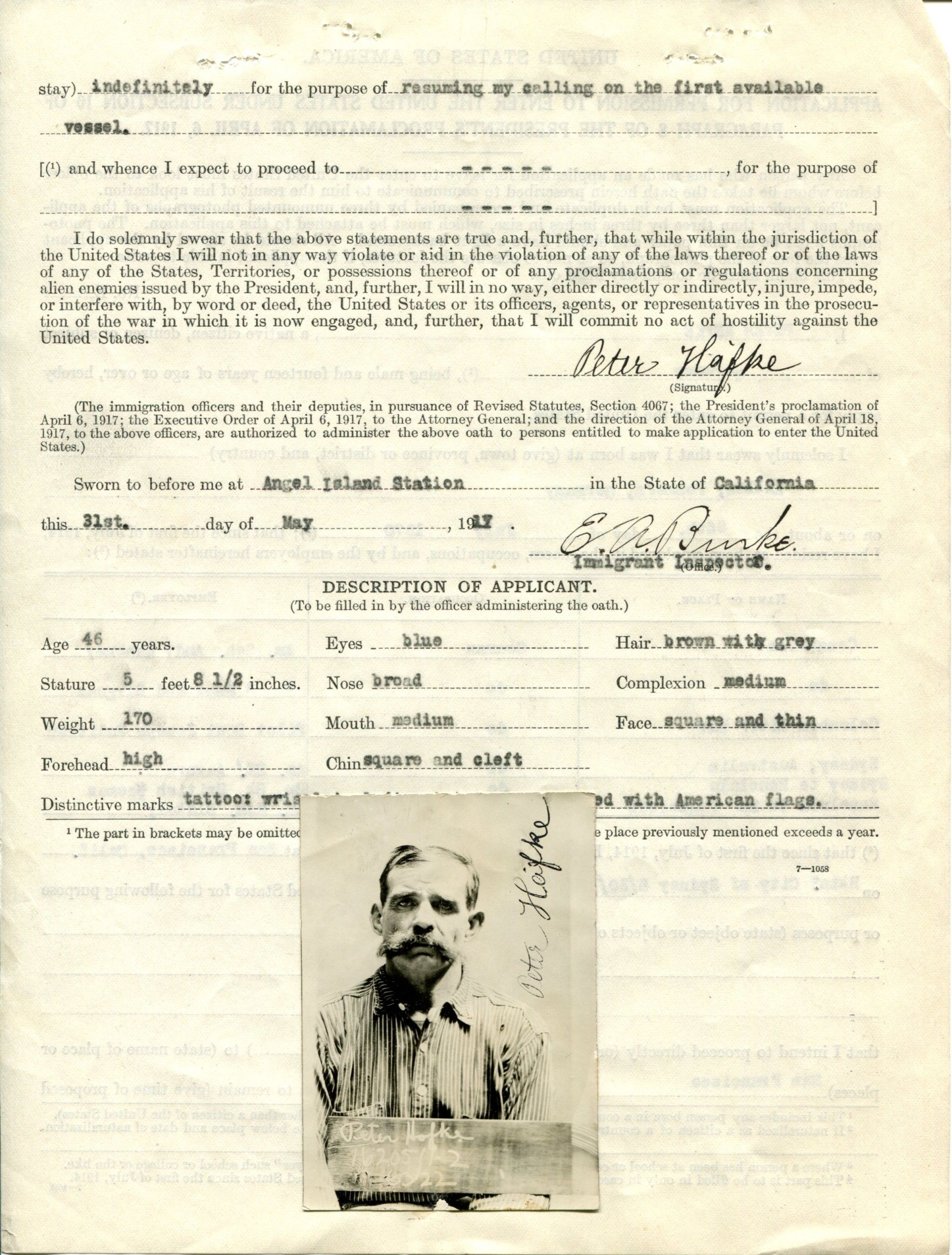

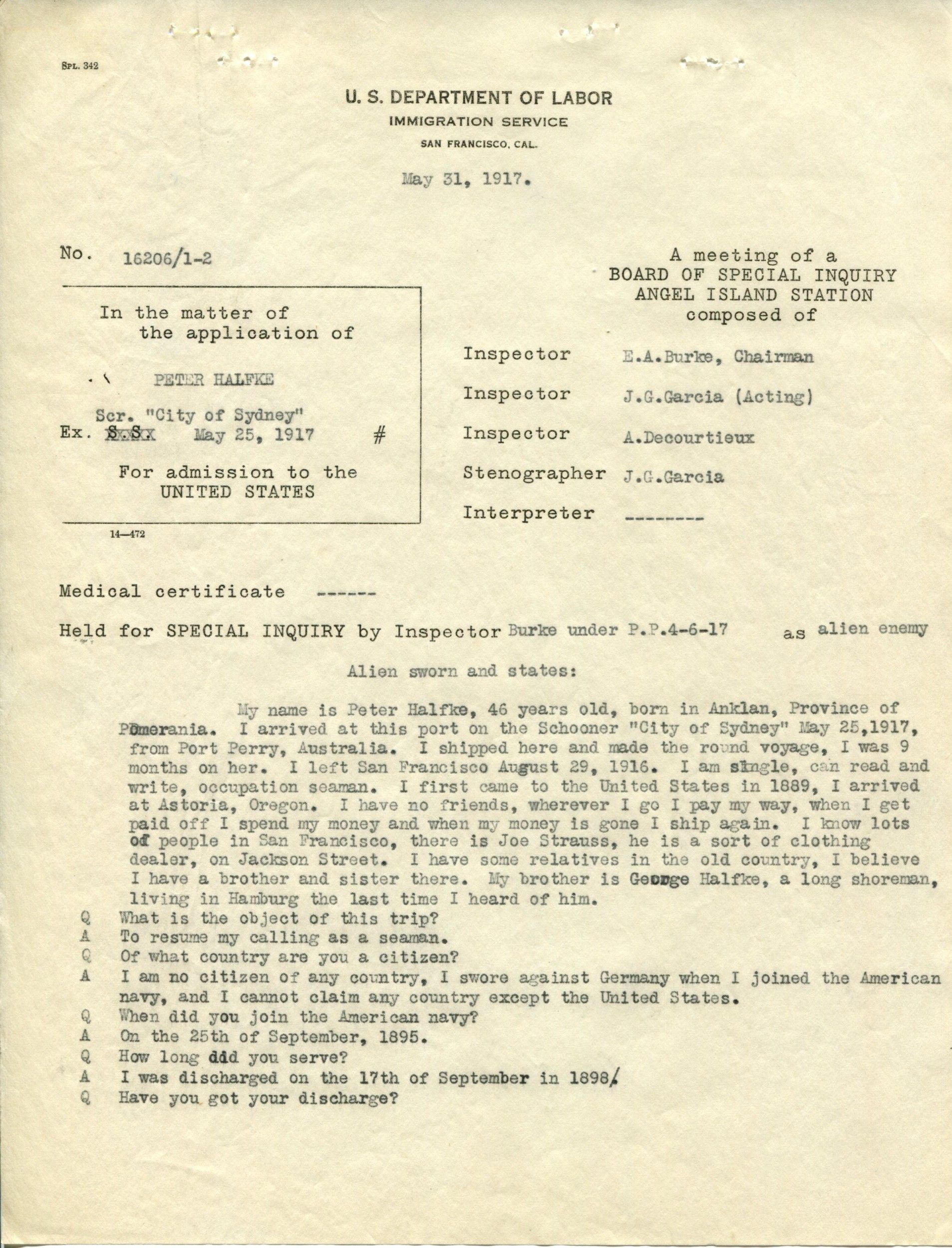

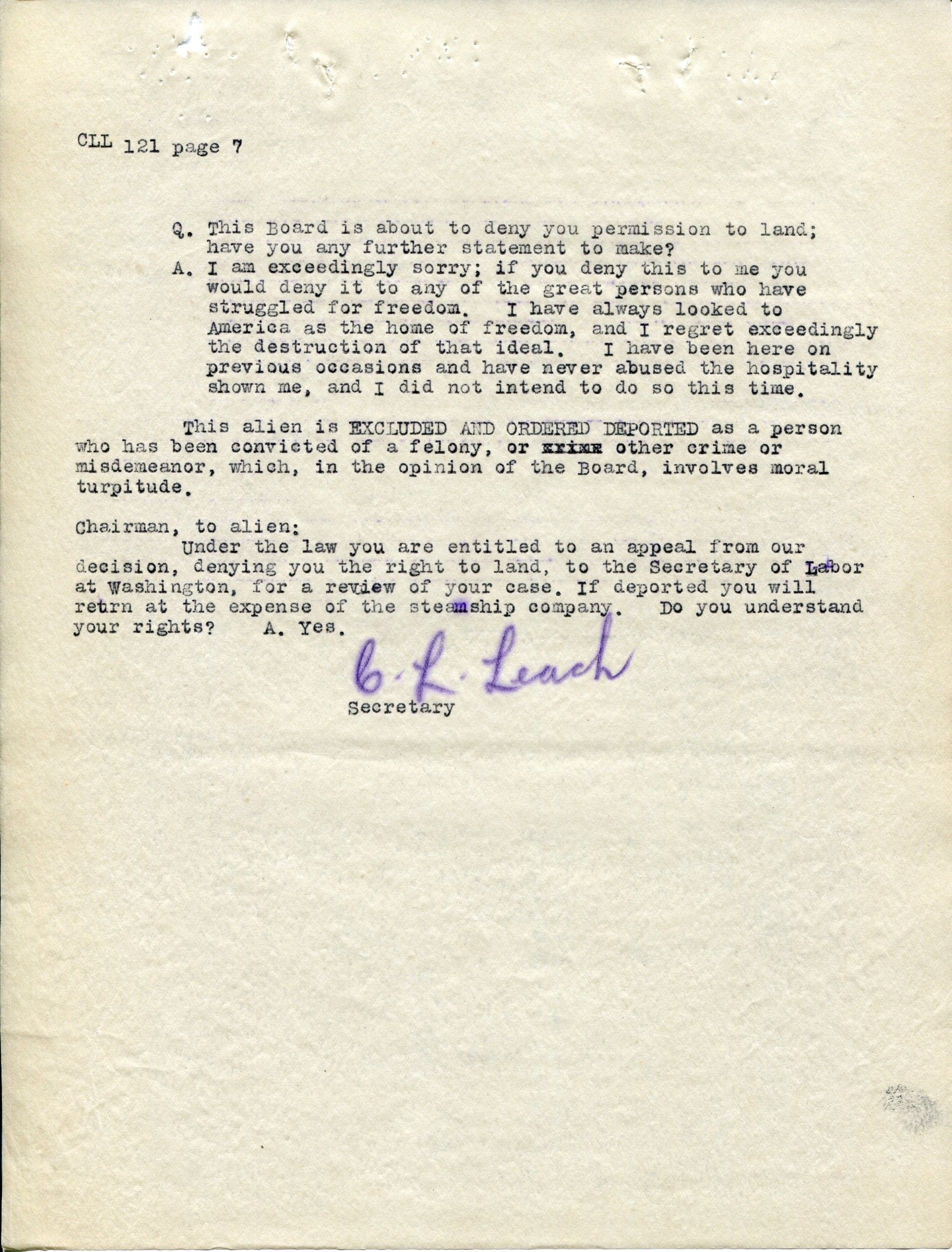

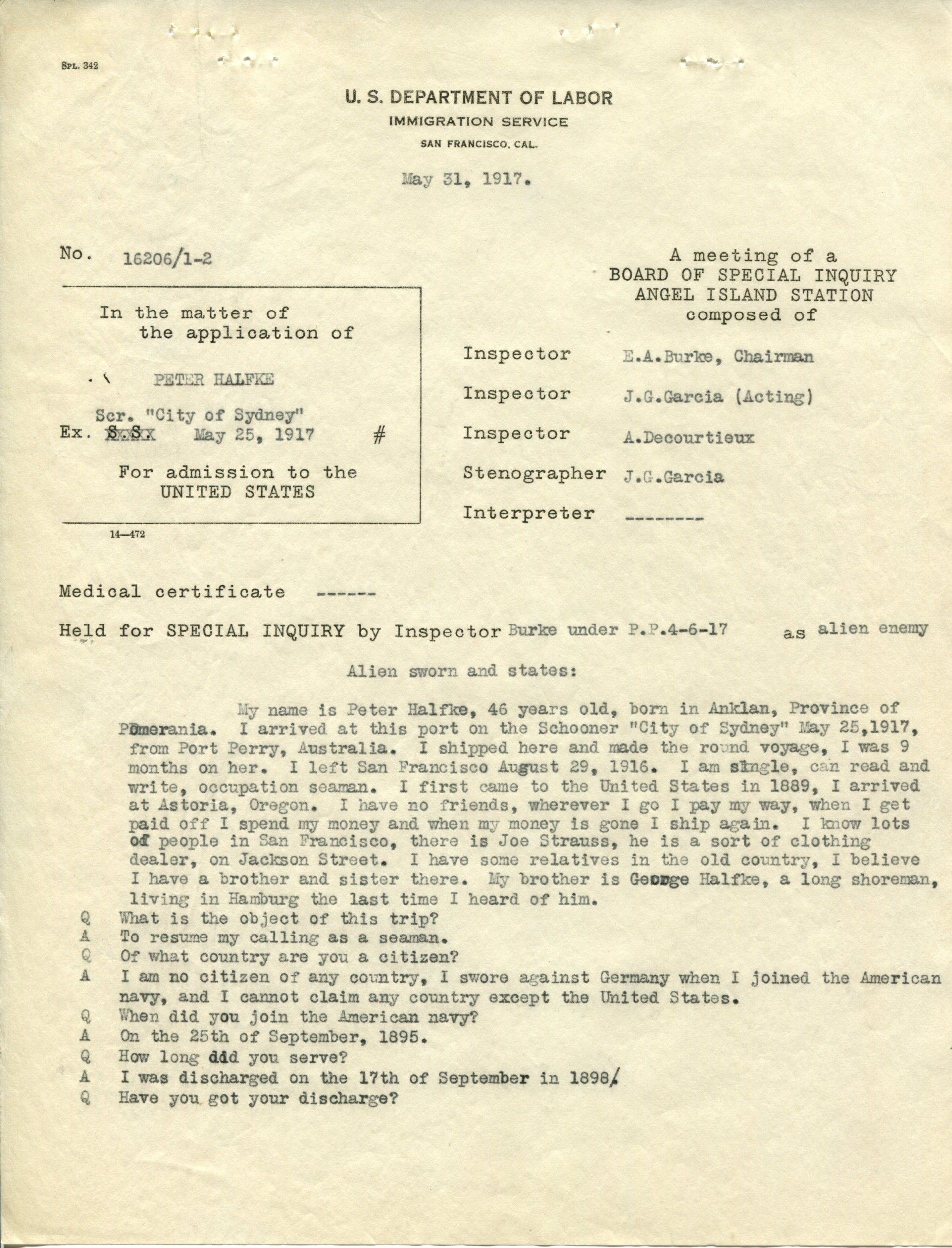

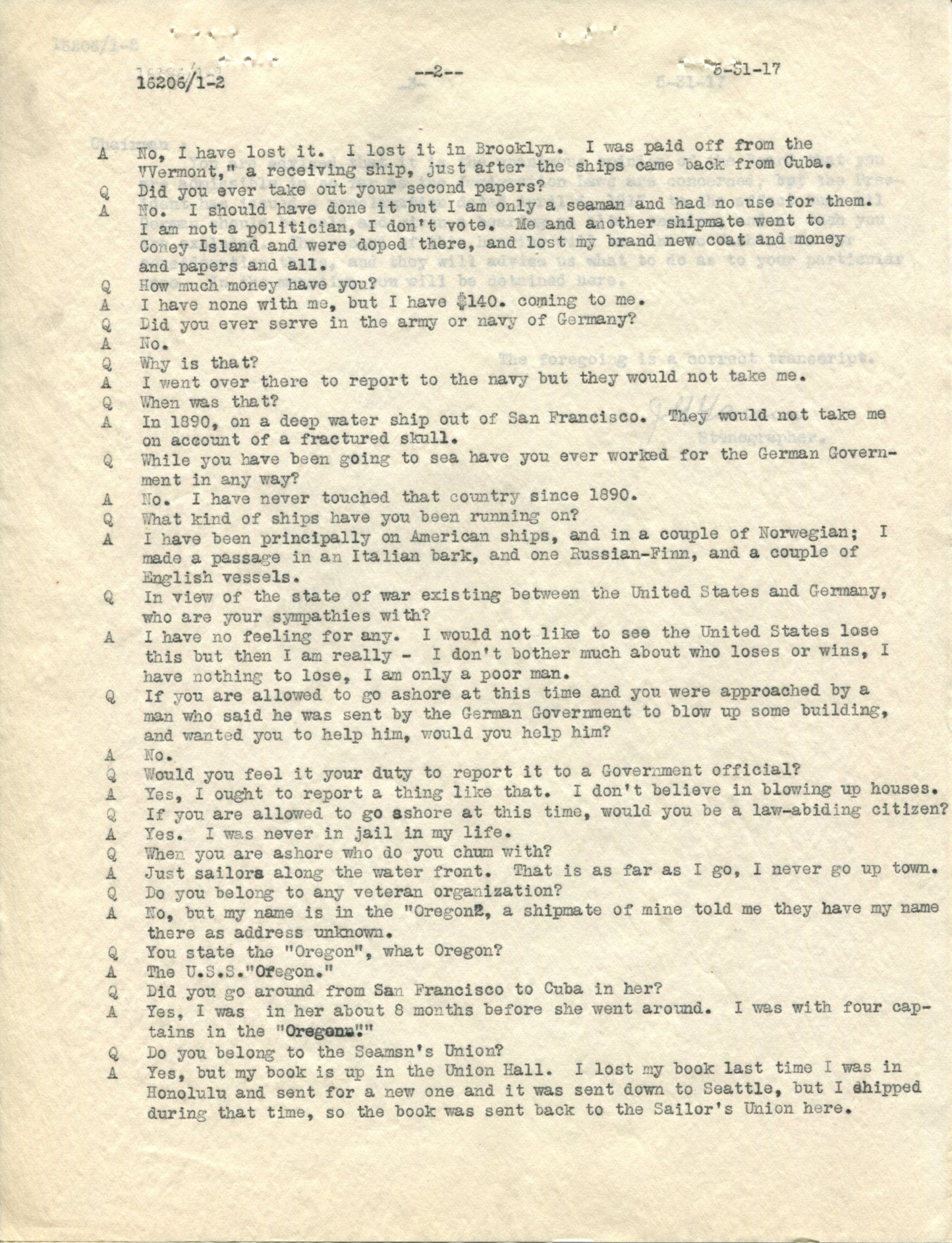

Transcript of Meeting of Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station with Enclosed Application to Enter the United States and Photograph

5/31/1917

This document is a transcript of a meeting of A Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station. It includes the sworn statement of Peter Halfke, who was forced to respond to questions about his national loyalties. It also includes his application to enter the United States, along with his photograph.

Halfke met the qualifications to enter the United States but was excluded as an "alien enemy" under the Presidential Proclamation of April 6, 1917, that declared war on Germany. President Woodrow Wilson called on residents in the United States, citizen and immigrant alike, to uphold all laws and provide support for all measures adopted in order to protect the nation and secure peace. For individuals termed "alien enemies" – all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of Germany (including American born women who married German men) – this showing of loyalty and devotion required a number of additional parameters and processes.

This document comes from a file about admissions by boards of special inquiry of unaccompanied children under 16 from 1917–1939.

It was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2014 Summer Workshop in Washington, D.C.

Halfke met the qualifications to enter the United States but was excluded as an "alien enemy" under the Presidential Proclamation of April 6, 1917, that declared war on Germany. President Woodrow Wilson called on residents in the United States, citizen and immigrant alike, to uphold all laws and provide support for all measures adopted in order to protect the nation and secure peace. For individuals termed "alien enemies" – all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of Germany (including American born women who married German men) – this showing of loyalty and devotion required a number of additional parameters and processes.

This document comes from a file about admissions by boards of special inquiry of unaccompanied children under 16 from 1917–1939.

It was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2014 Summer Workshop in Washington, D.C.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

National Archives Identifier: 12013859

Full Citation: Transcript of Meeting of Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station with Enclosed Application to Enter the United States and Photograph; 5/31/1917; 54278/154; General File - Admissions by Boards of Special Inquiry of Unaccompanied Children Under 16 - Rule 6; Subject and Policy Files, 1906 - 1957; Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/application-halfke, April 19, 2024]Transcript of Meeting of Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station with Enclosed Application to Enter the United States and Photograph

Page 1

Transcript of Meeting of Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station with Enclosed Application to Enter the United States and Photograph

Page 3

Transcript of Meeting of Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station with Enclosed Application to Enter the United States and Photograph

Page 2

Transcript of Meeting of Board of Special Inquiry at Angel Island Station with Enclosed Application to Enter the United States and Photograph

Page 4