From Dred Scott to the Civil Rights Act of 1875

Making Connections

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

In just 18 years (1857–1875), African-Americans went from enslavement and a U.S. Supreme Court ruling concluding that they were not citizens and were not entitled to the protection of the Federal government (Dred Scott decision), to becoming American citizens with voting rights and access to public transportation, lodging, and other facilities (the Civil Rights Act of 1875). How did this happen?Look at the documents and the events they represent. How are the adjacent documents related to each other?

Click on the "Enter Your Response" tab in the middle of the documents and explain the relationship between these adjacent documents (and what the documents represent).

Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

From Dred Scott to the Civil Rights Act of 1875

Making Connections

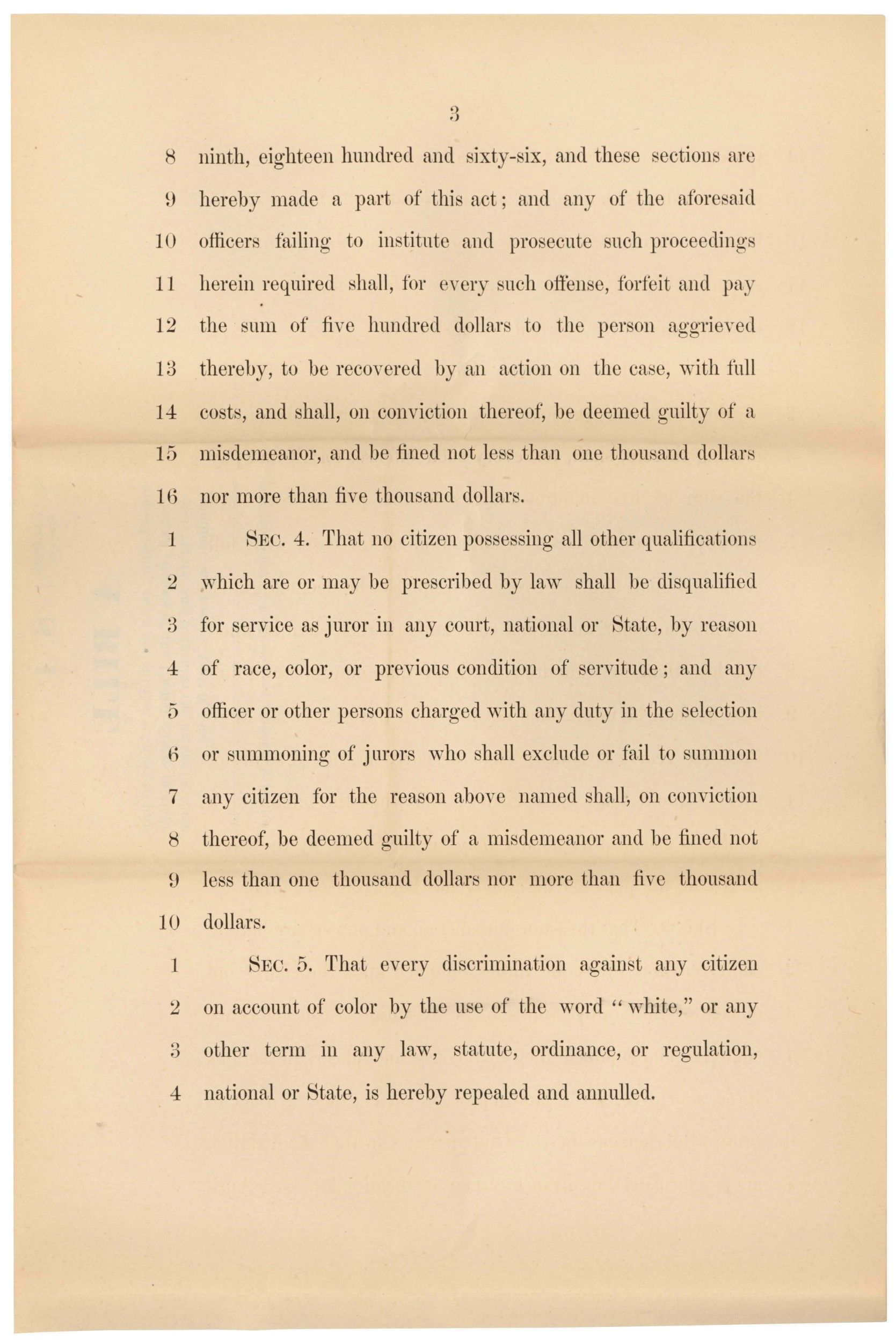

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Fill in any blanks in the sequence with your thoughts and write your conclusion response in the space provided.Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford

Enter your response

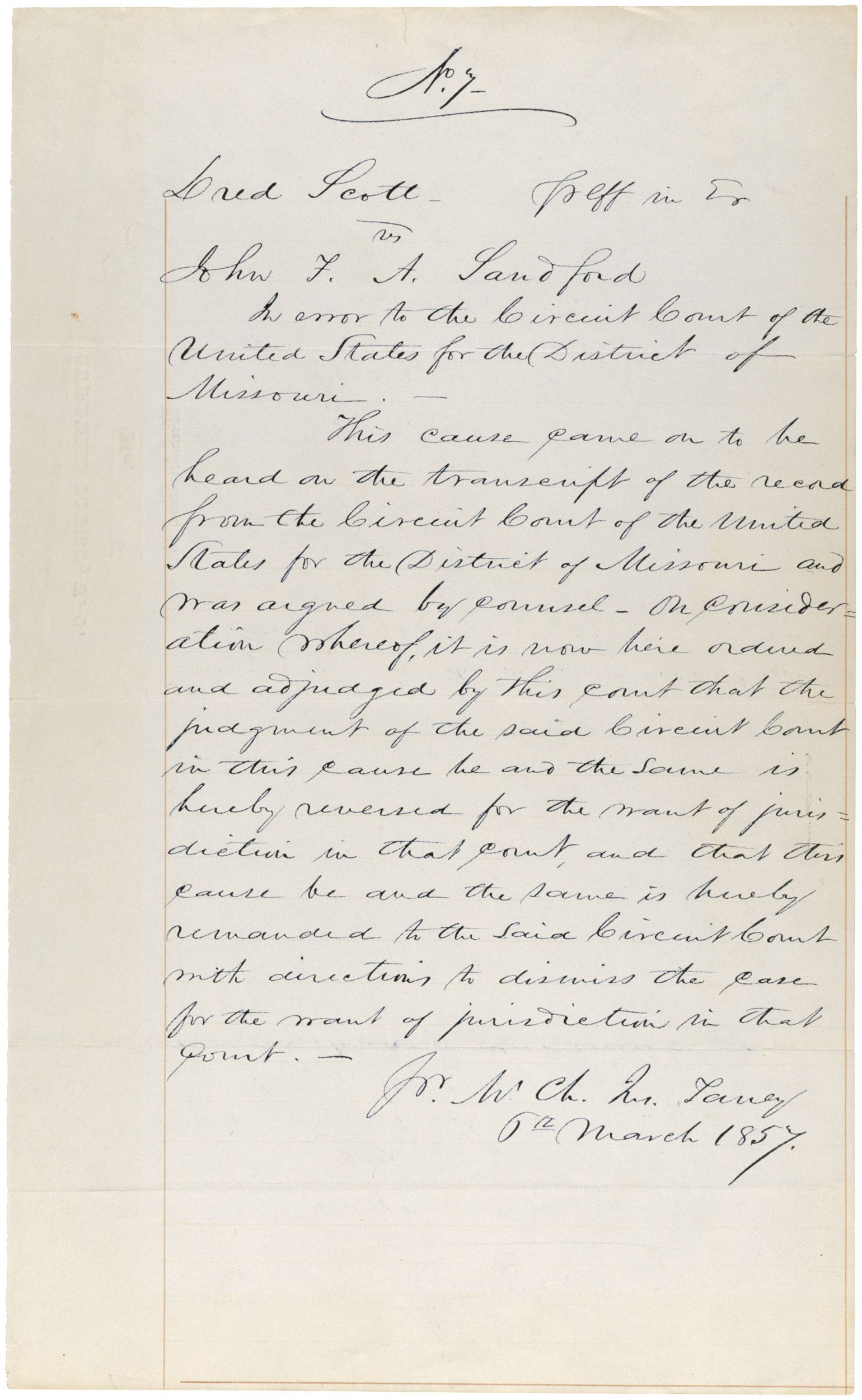

Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln

Enter your response

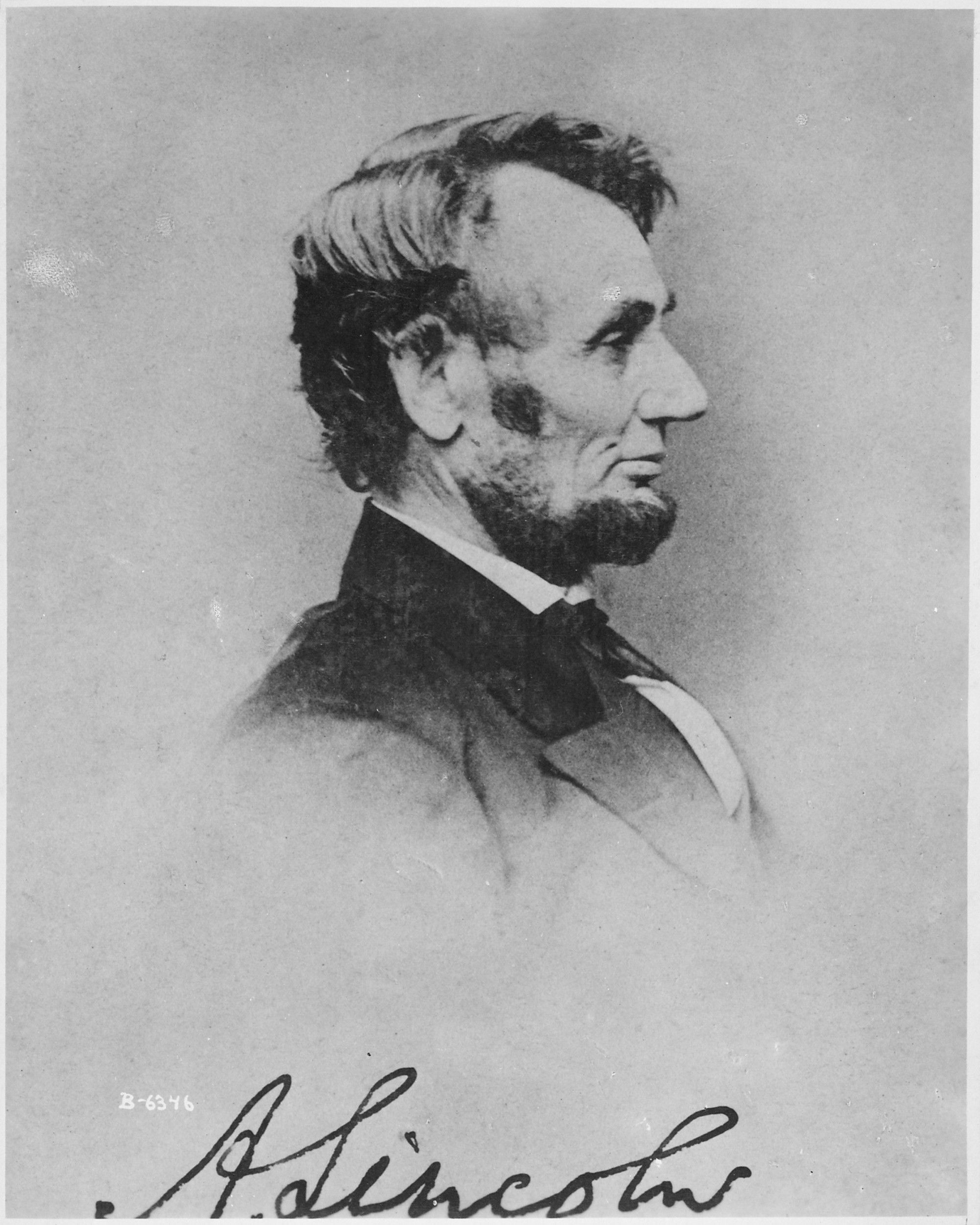

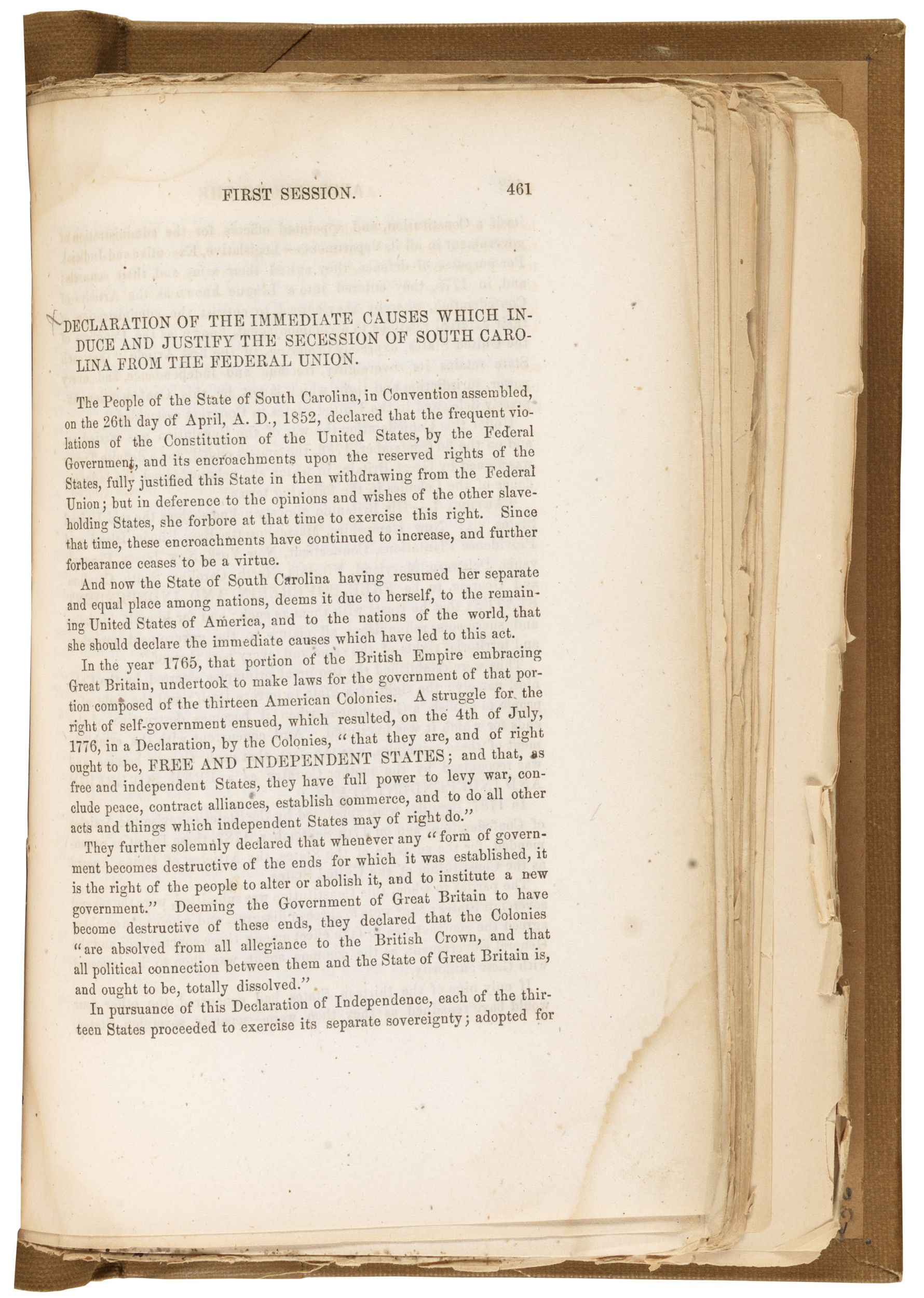

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Enter your response

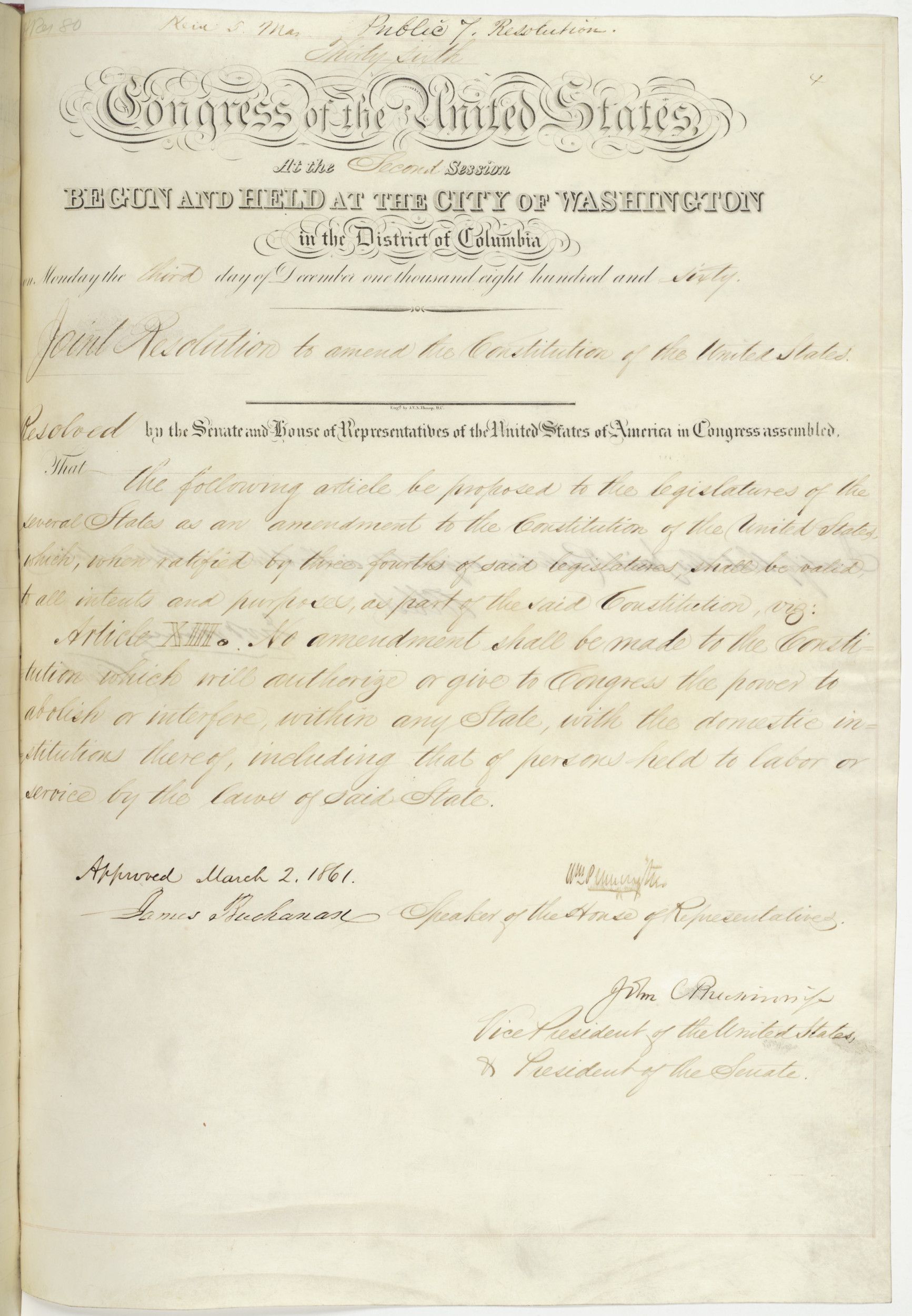

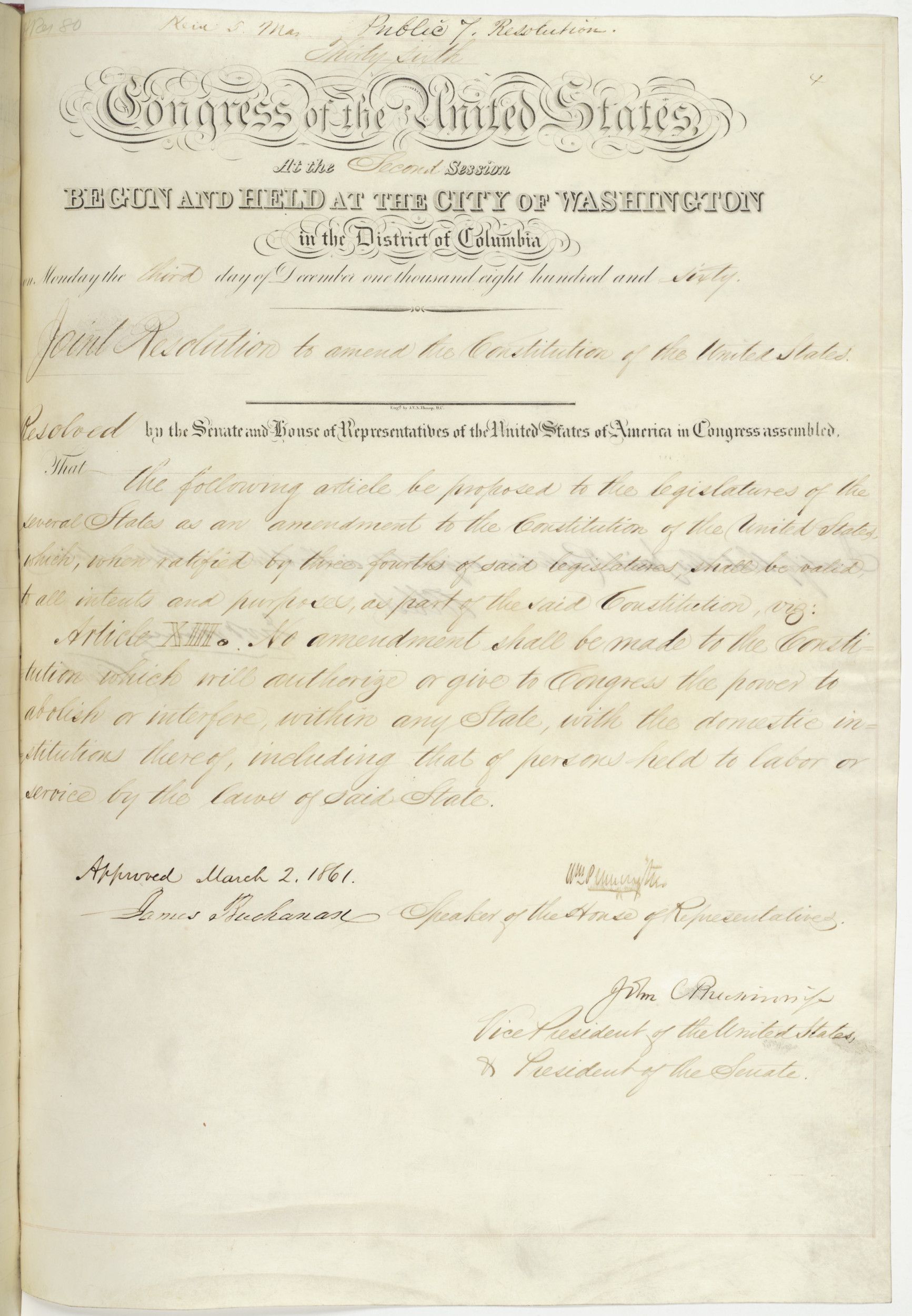

Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

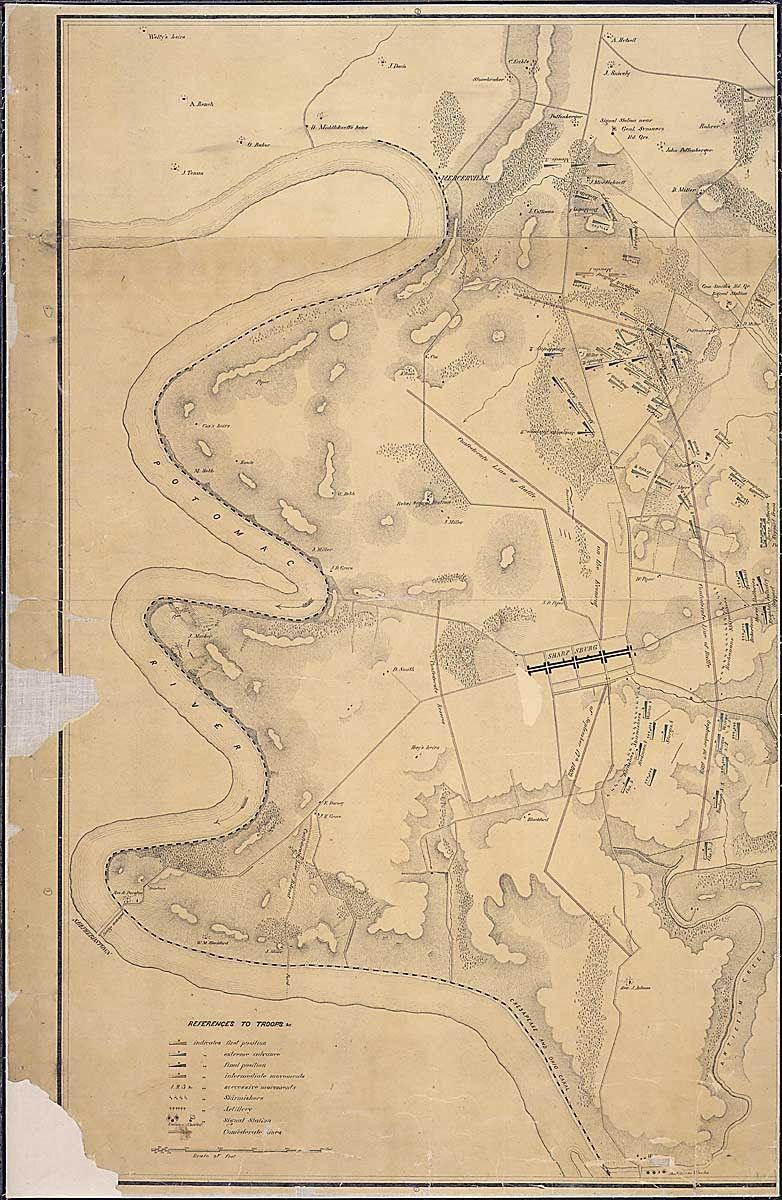

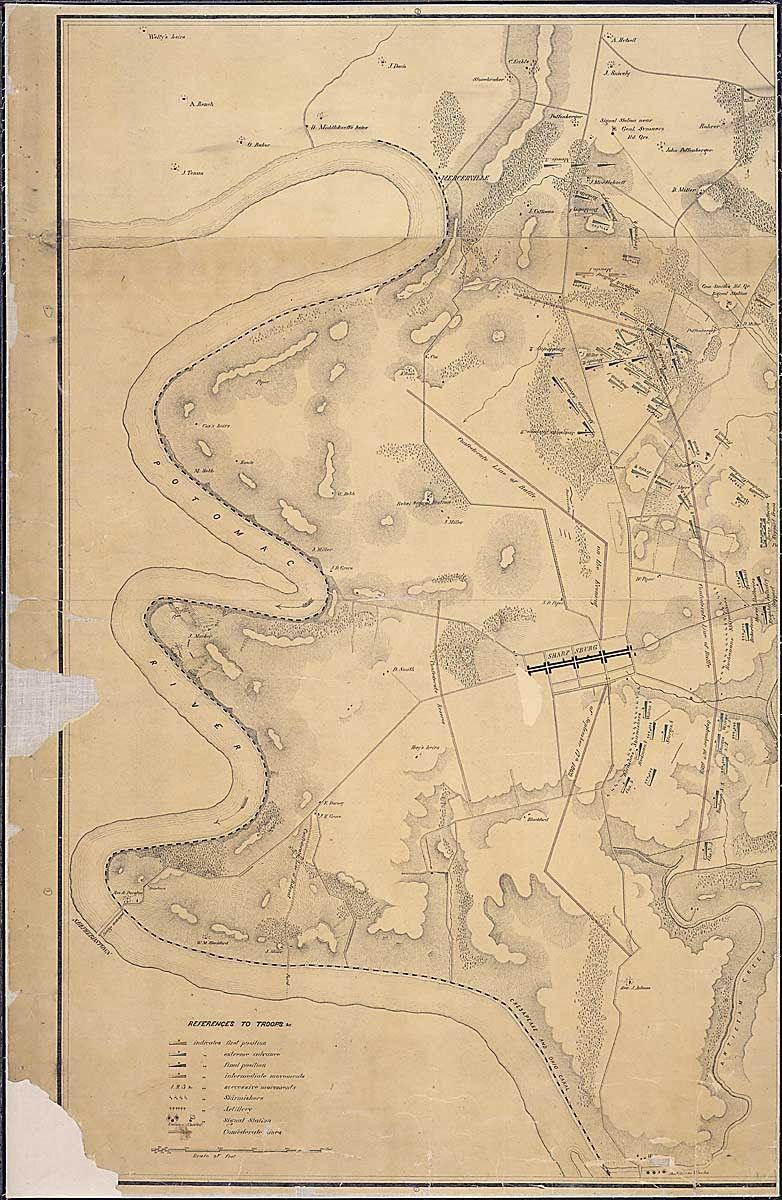

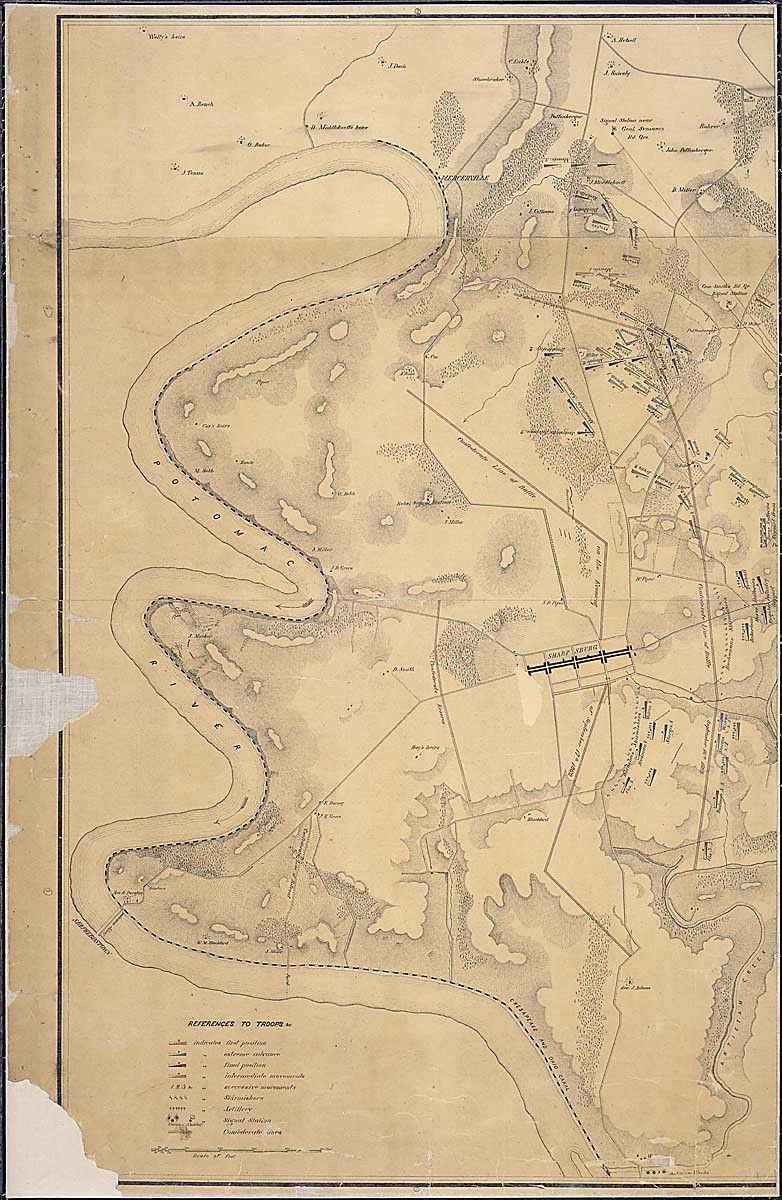

Map of the Battle of the Antietam fought on the 16th and 17th September 1862 between the United States Forces under the Command of Maj. Genl. Geo. B. McClellan and the Confederates under Genl. Robt. E

Enter your response

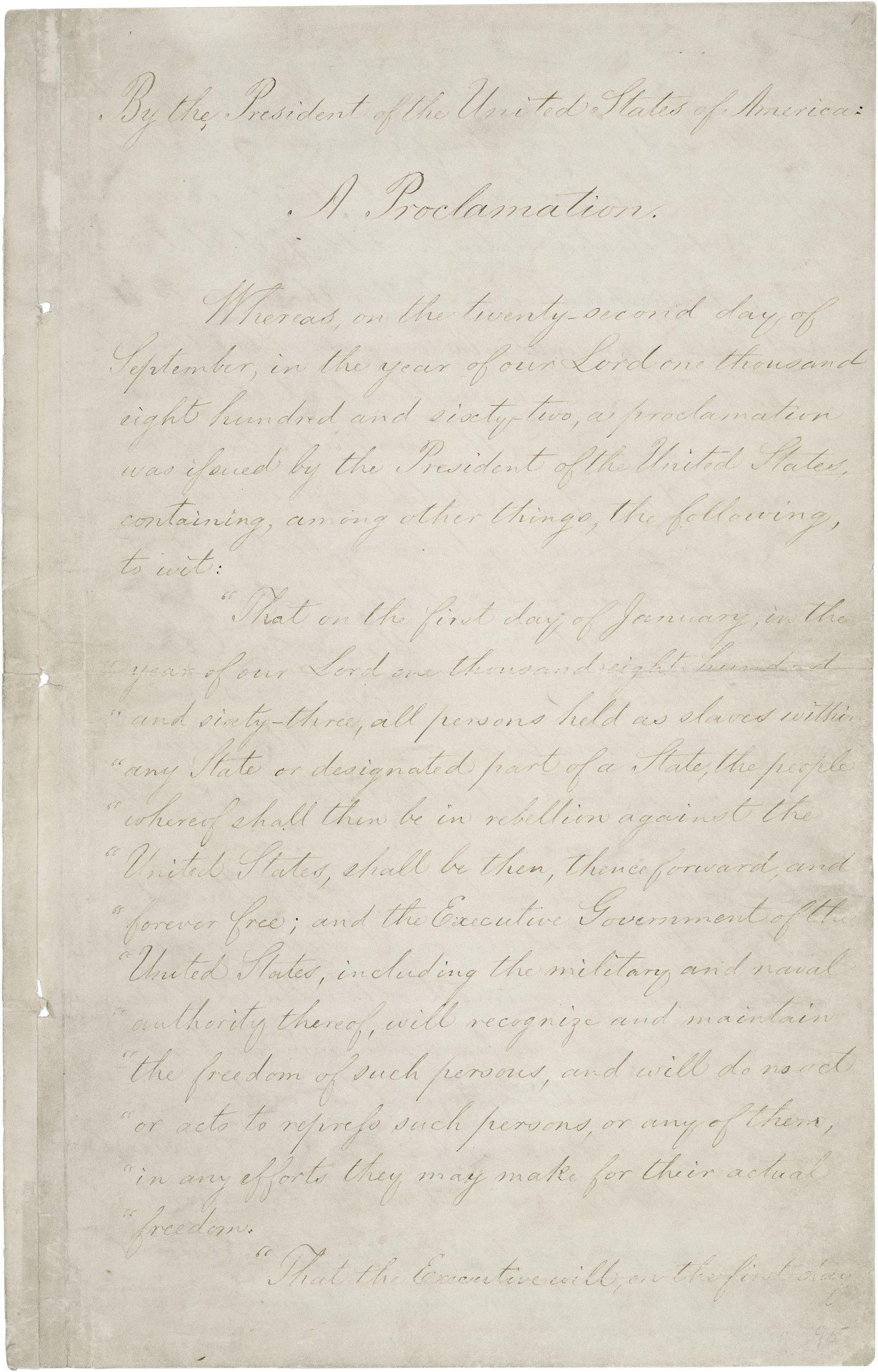

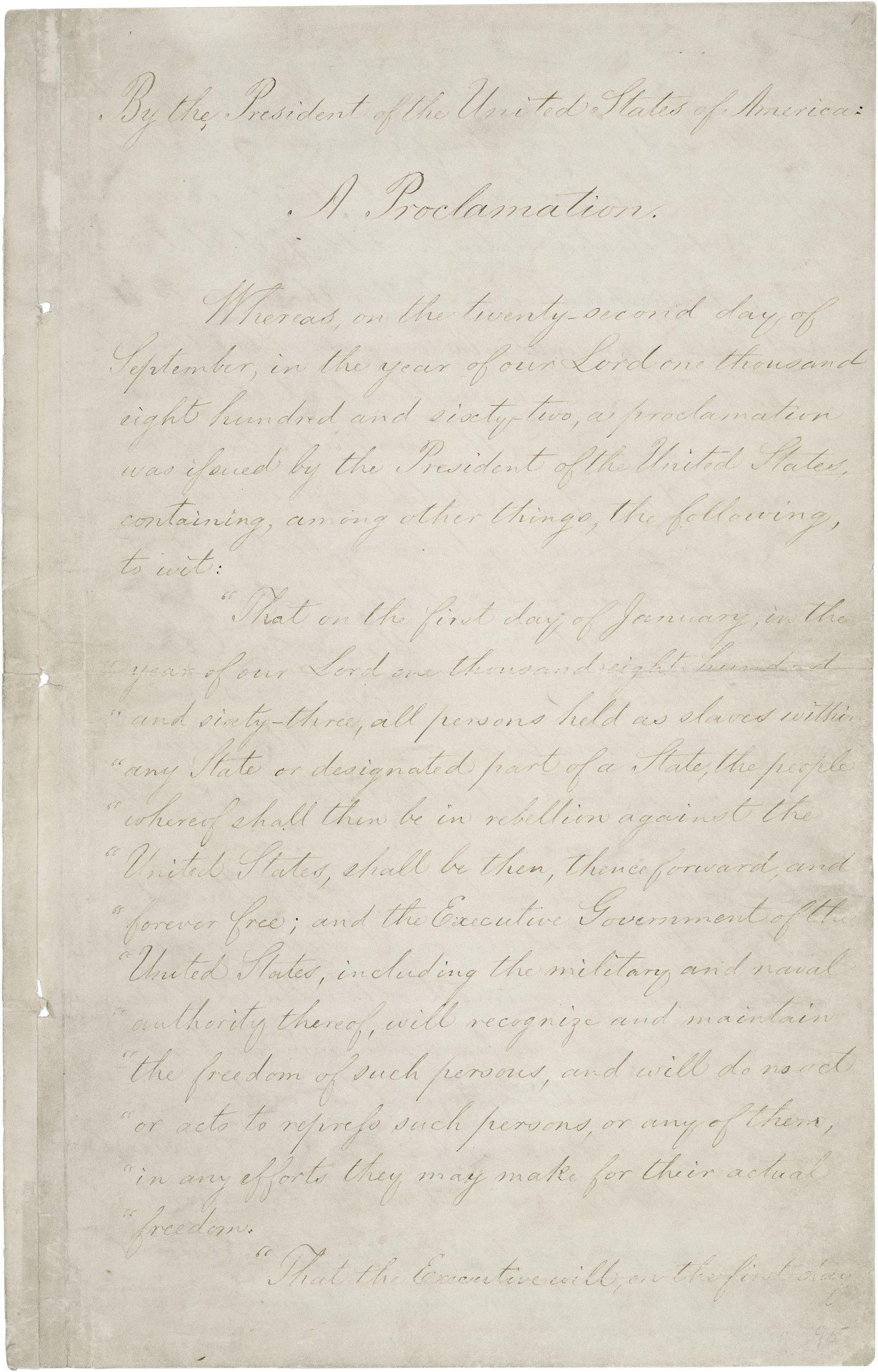

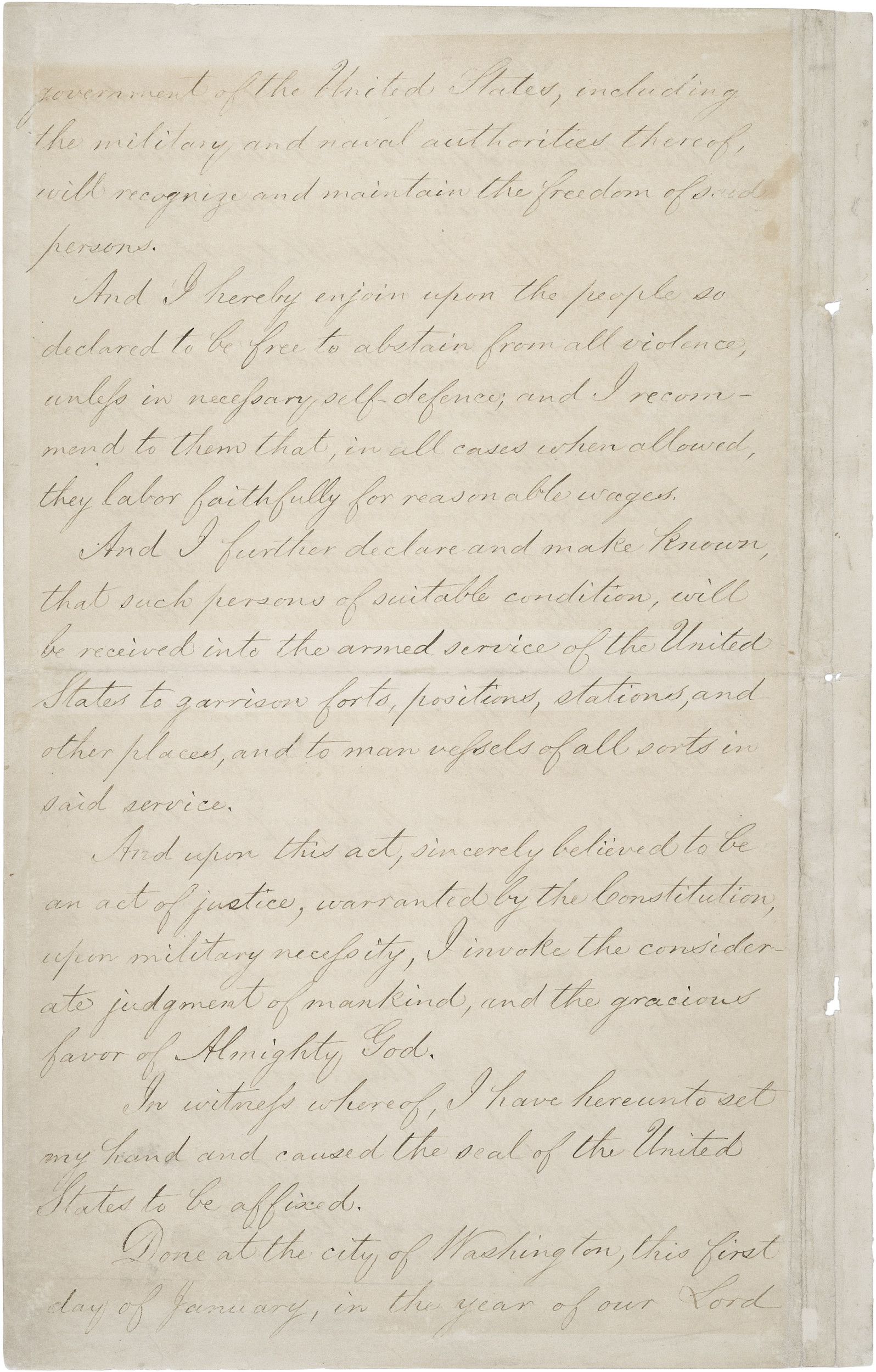

Emancipation Proclamation

Enter your response

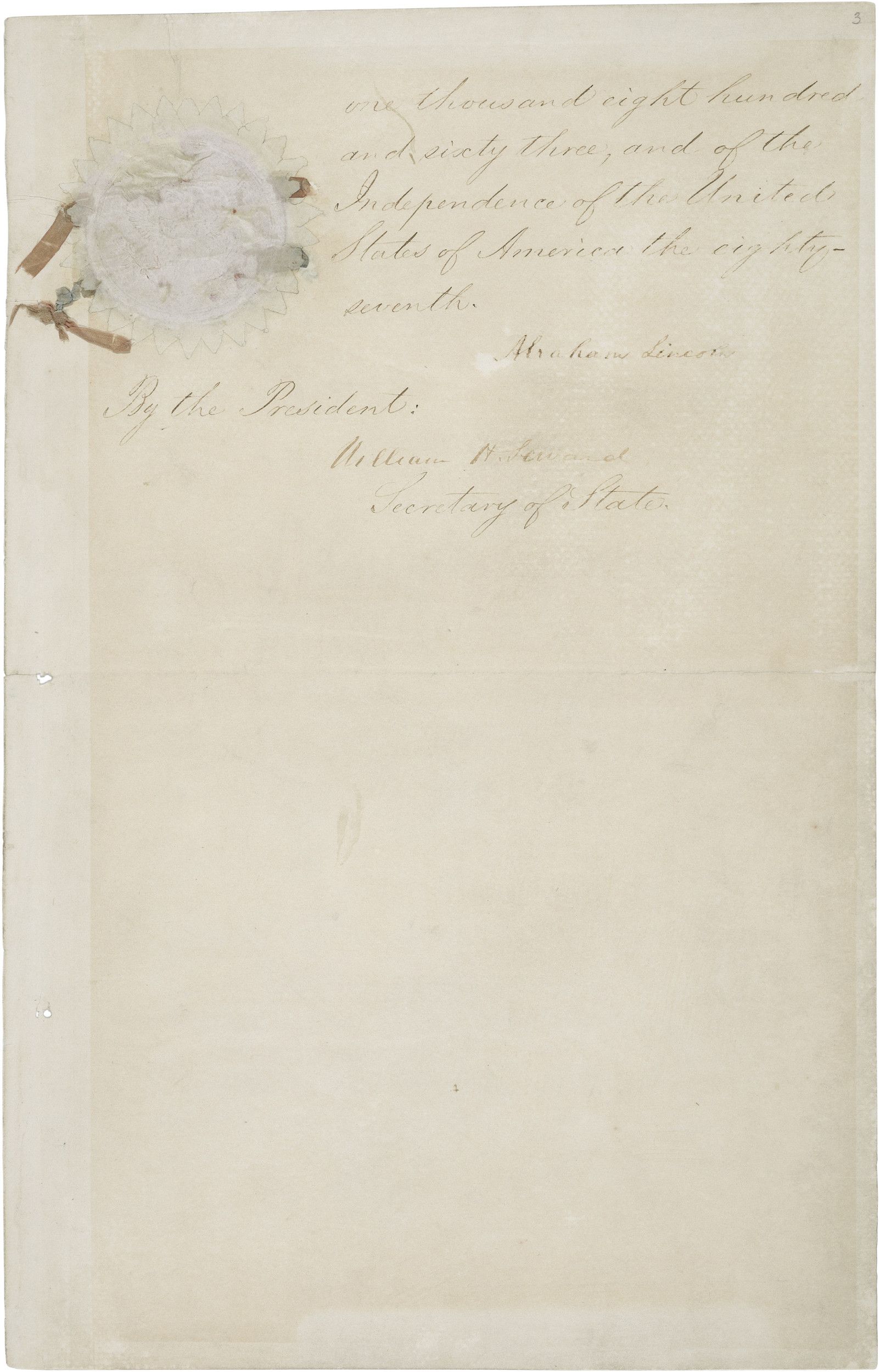

Photograph of United States Colored Troops at Port Hudson, Louisiana

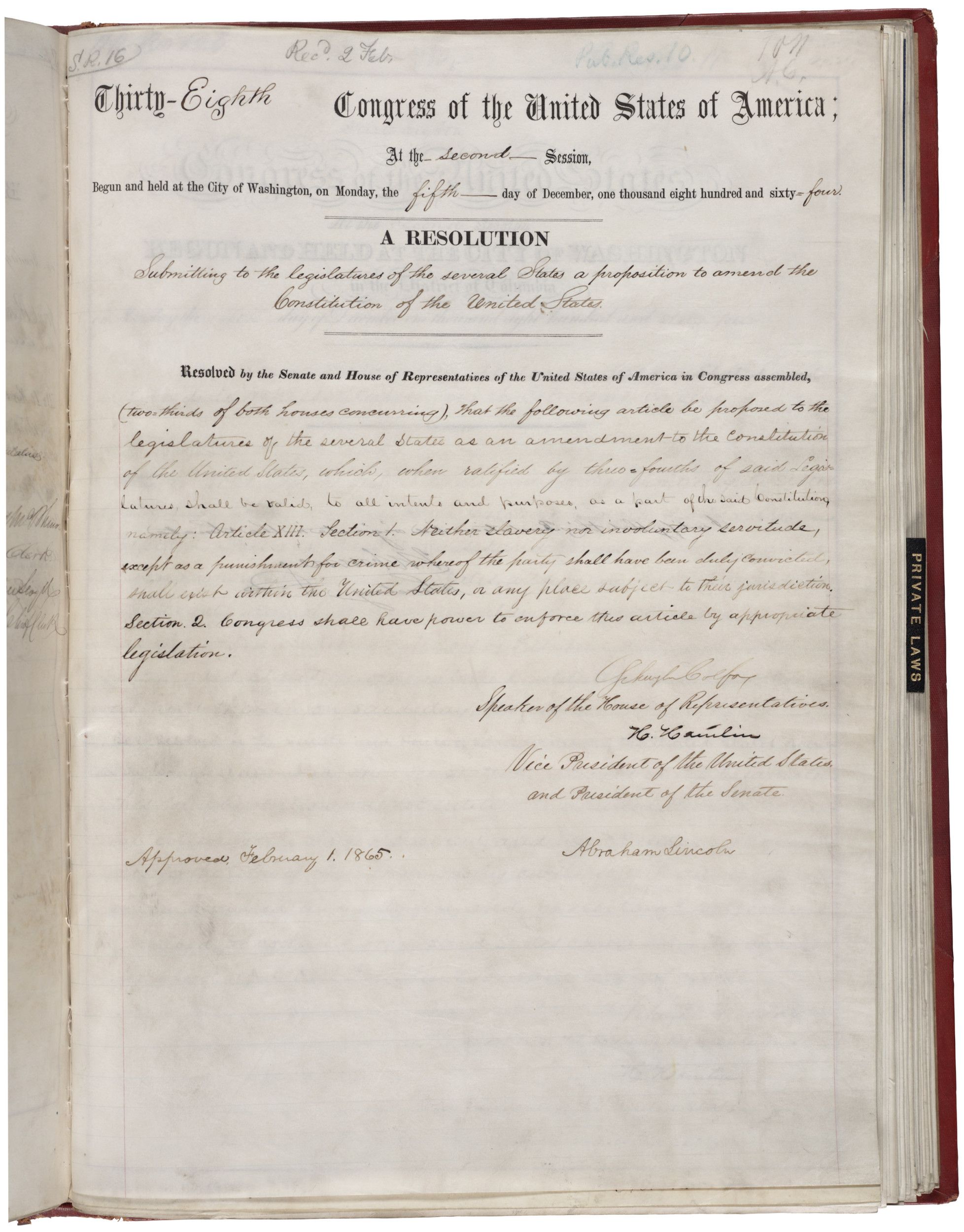

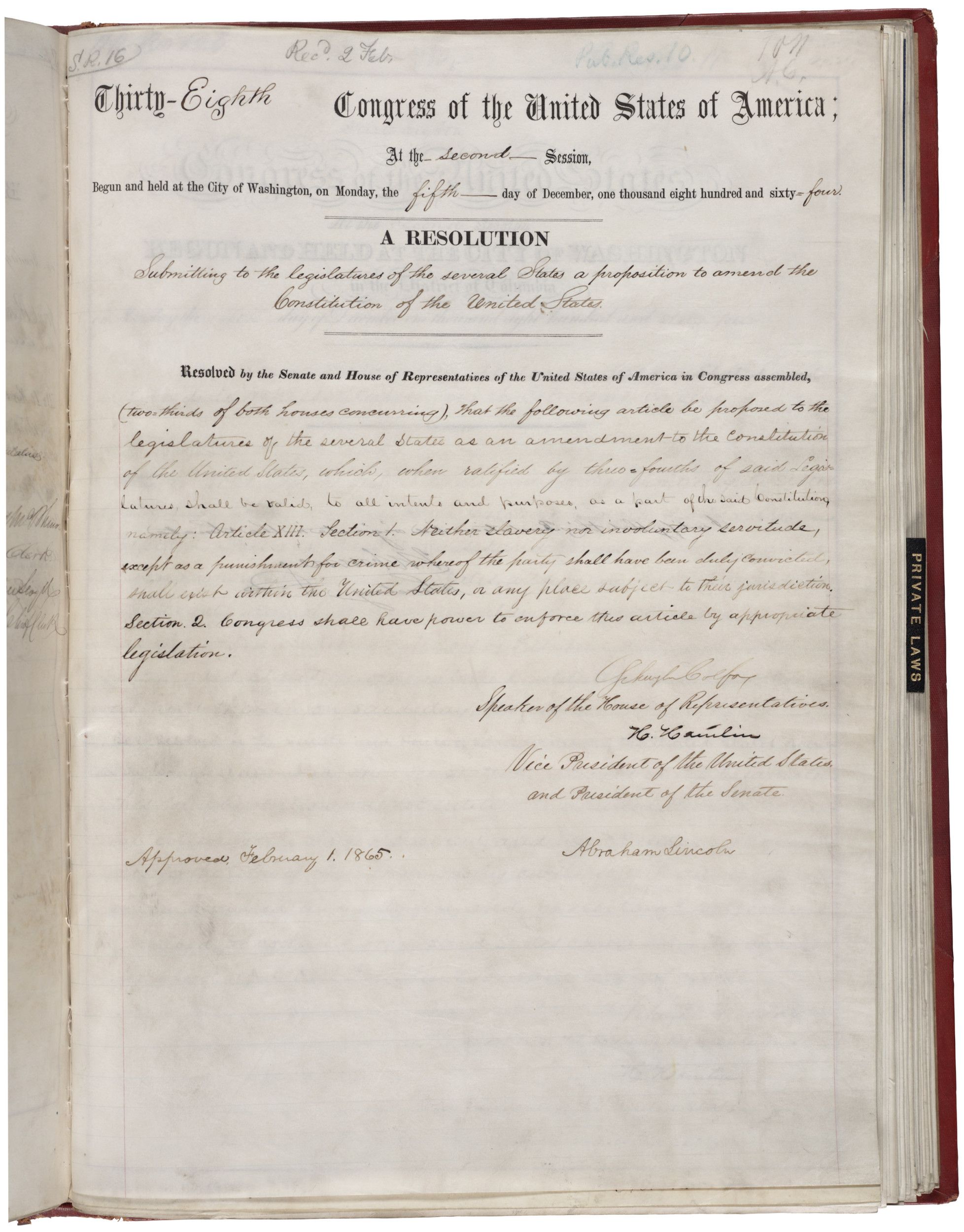

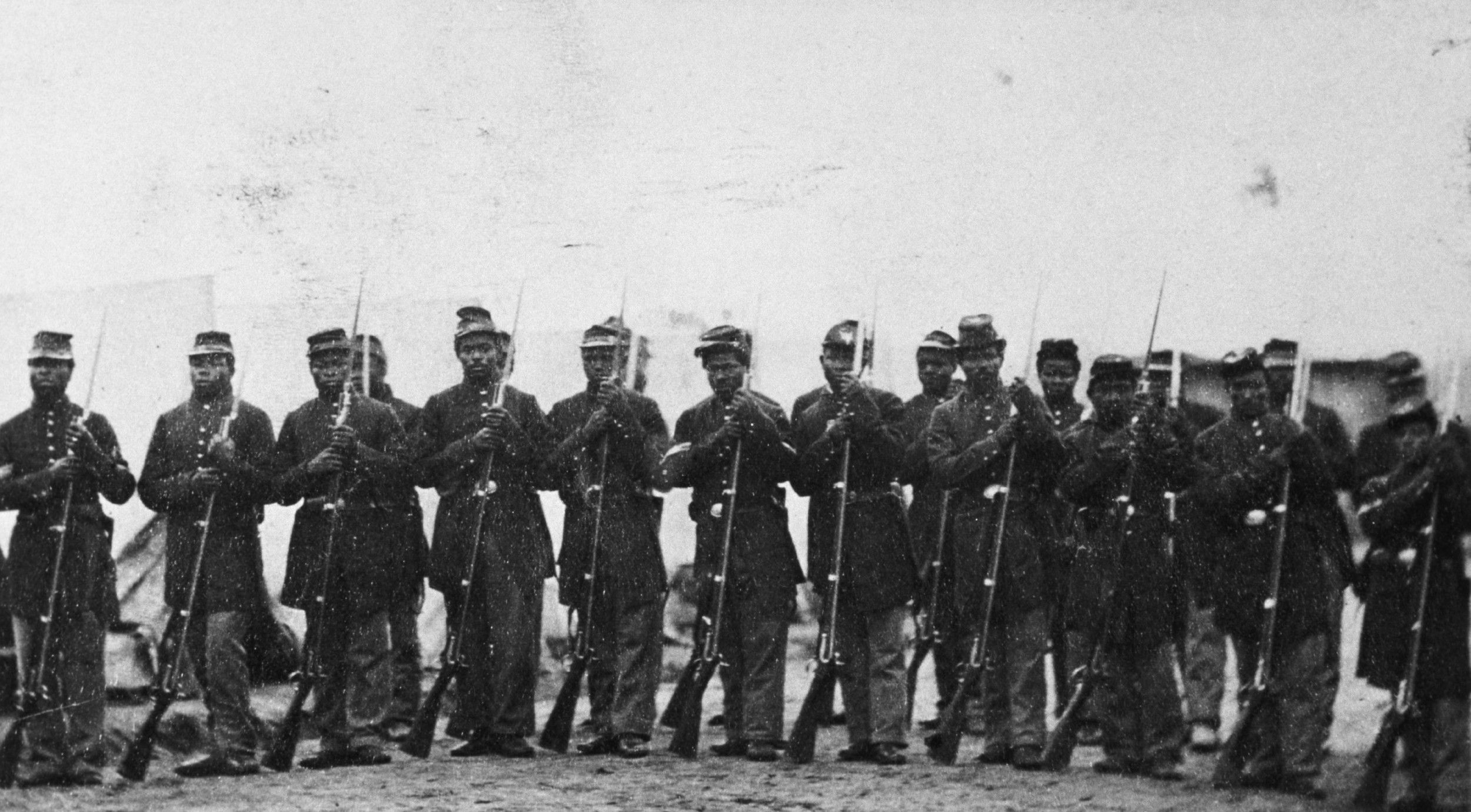

Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Enter your response

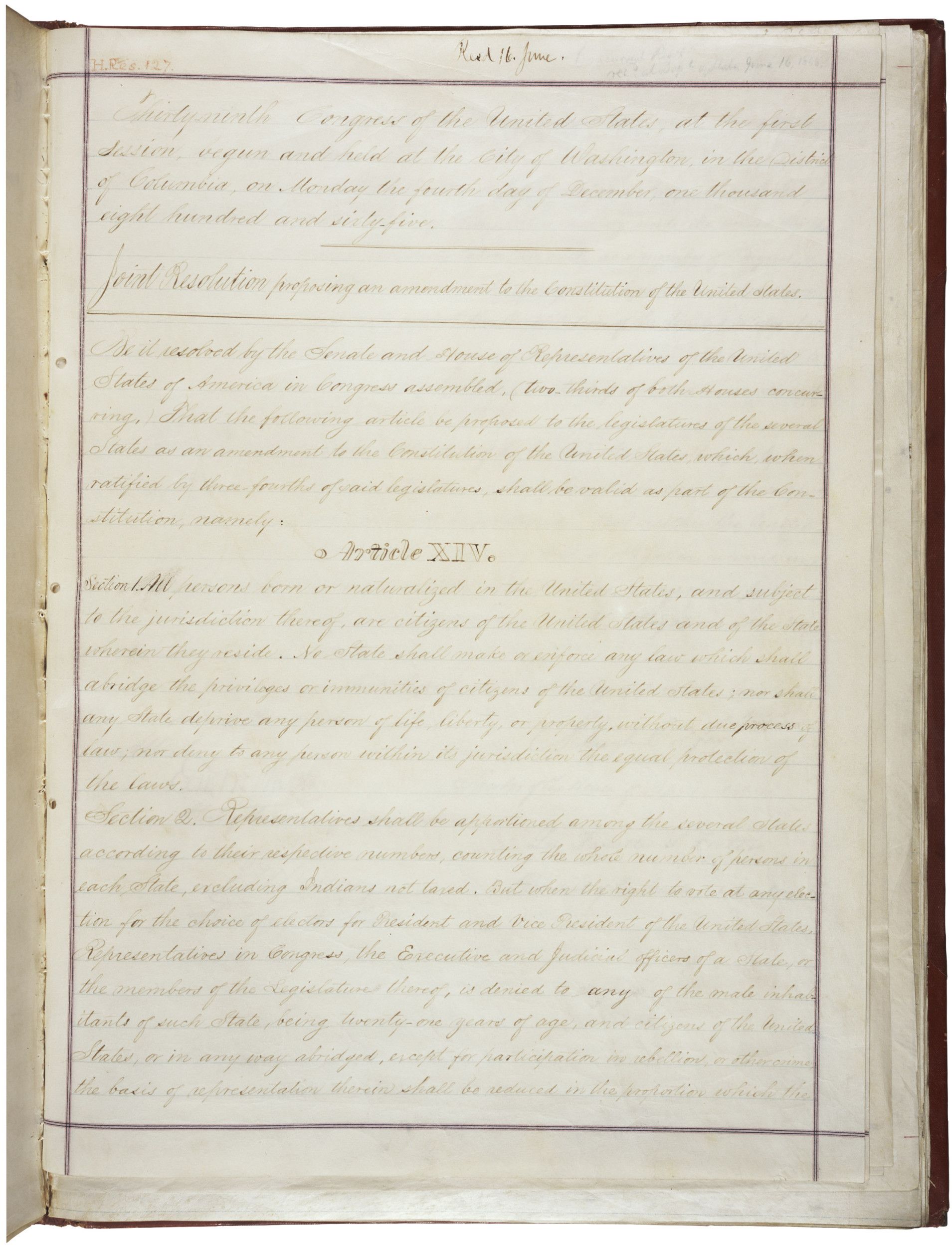

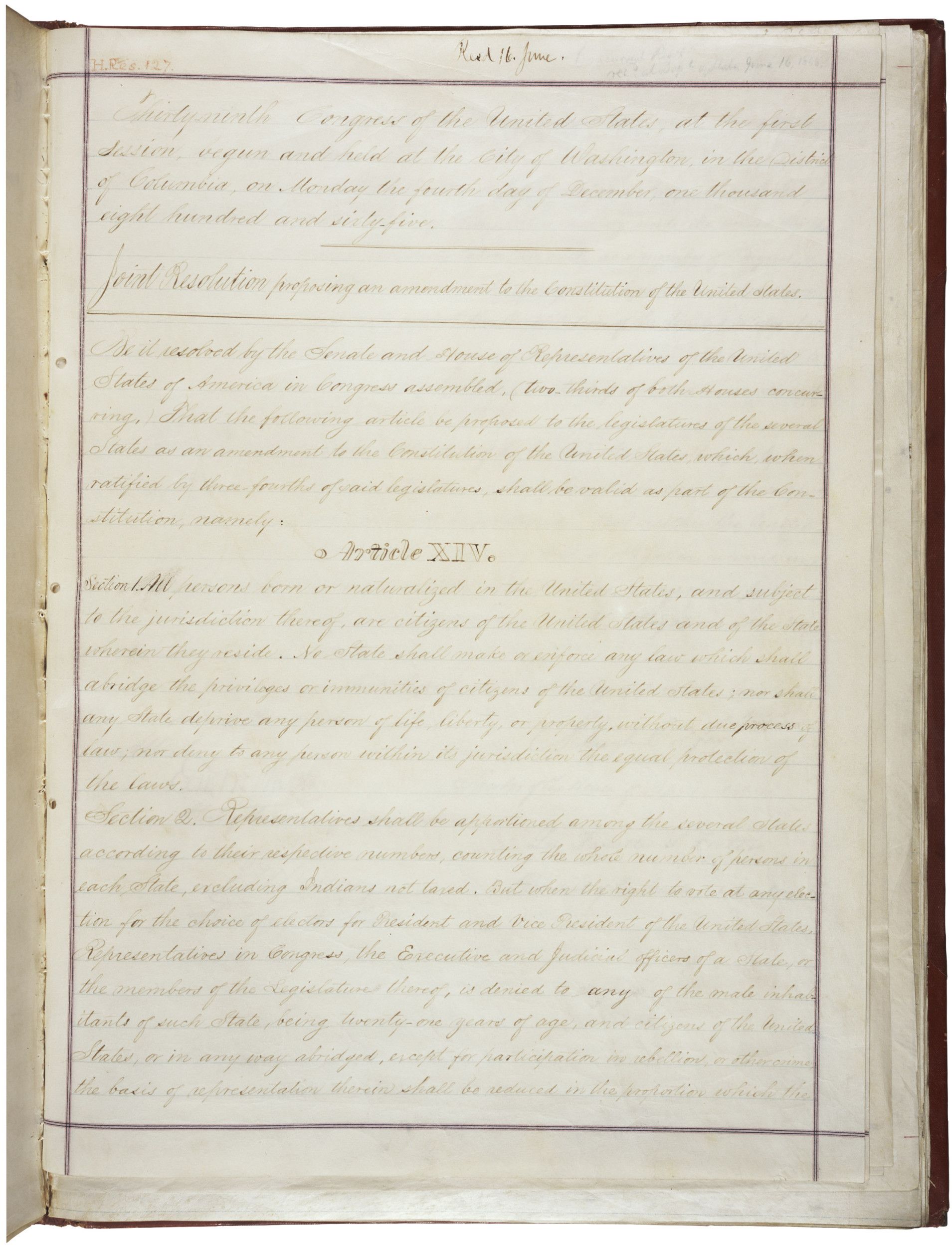

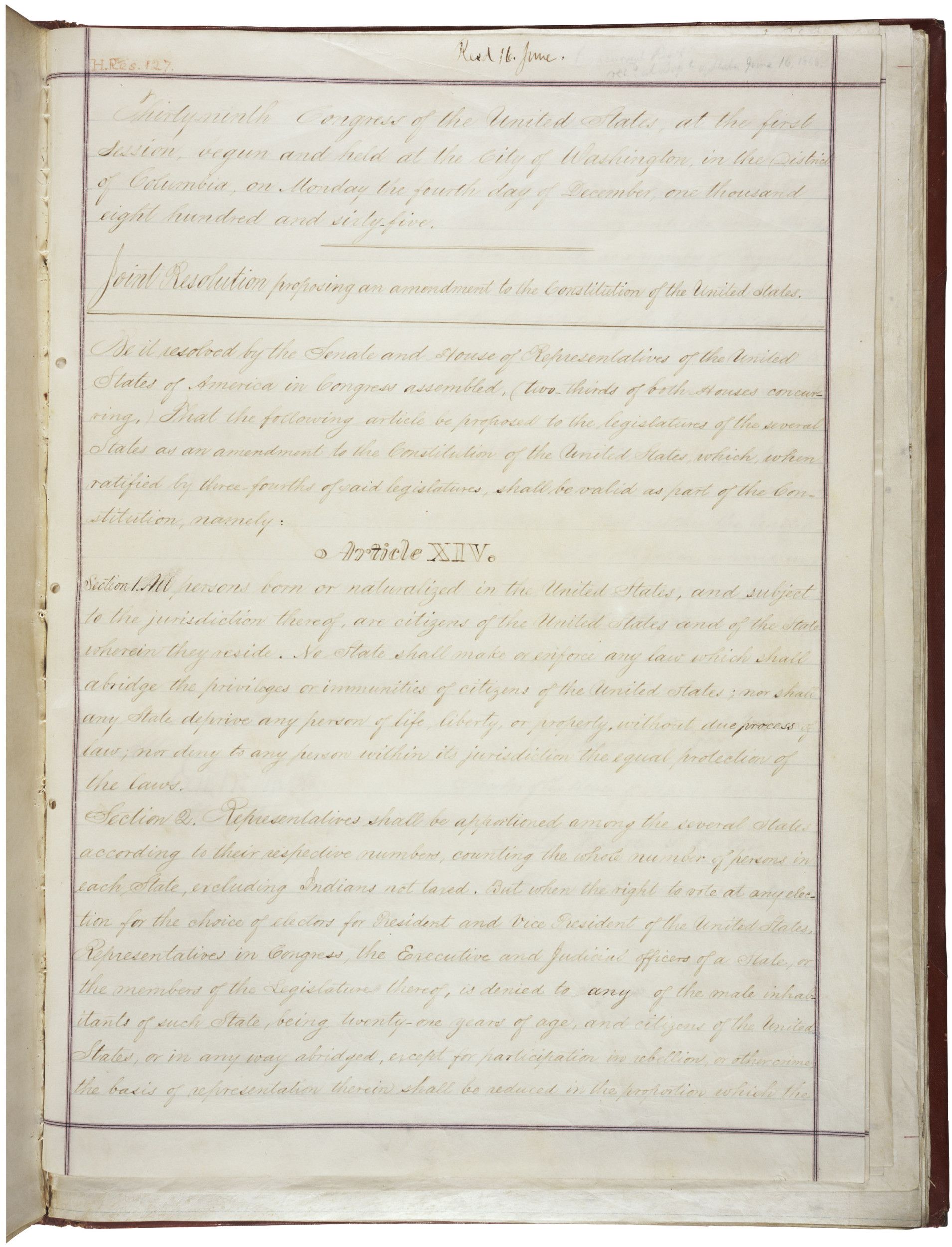

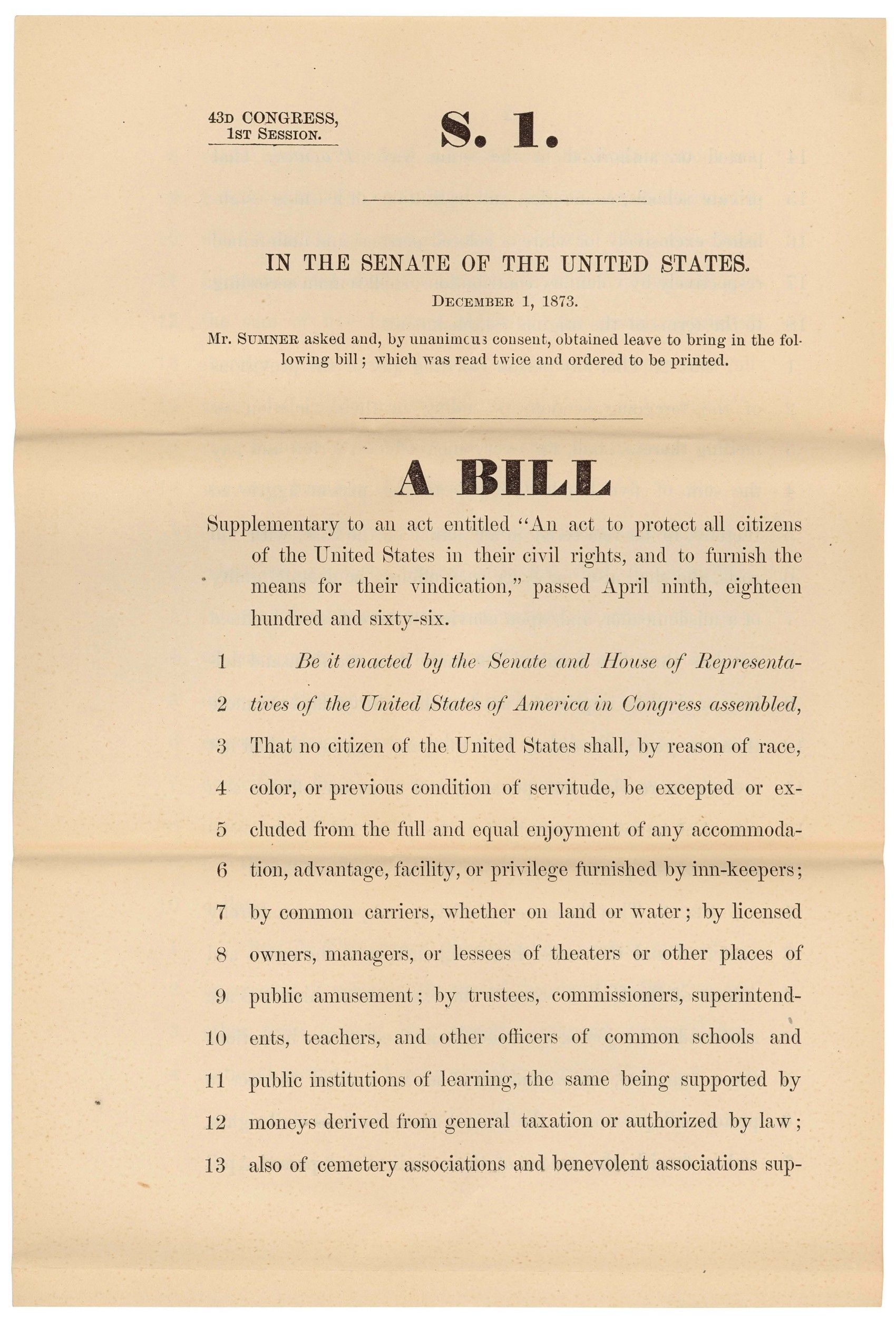

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Enter your response

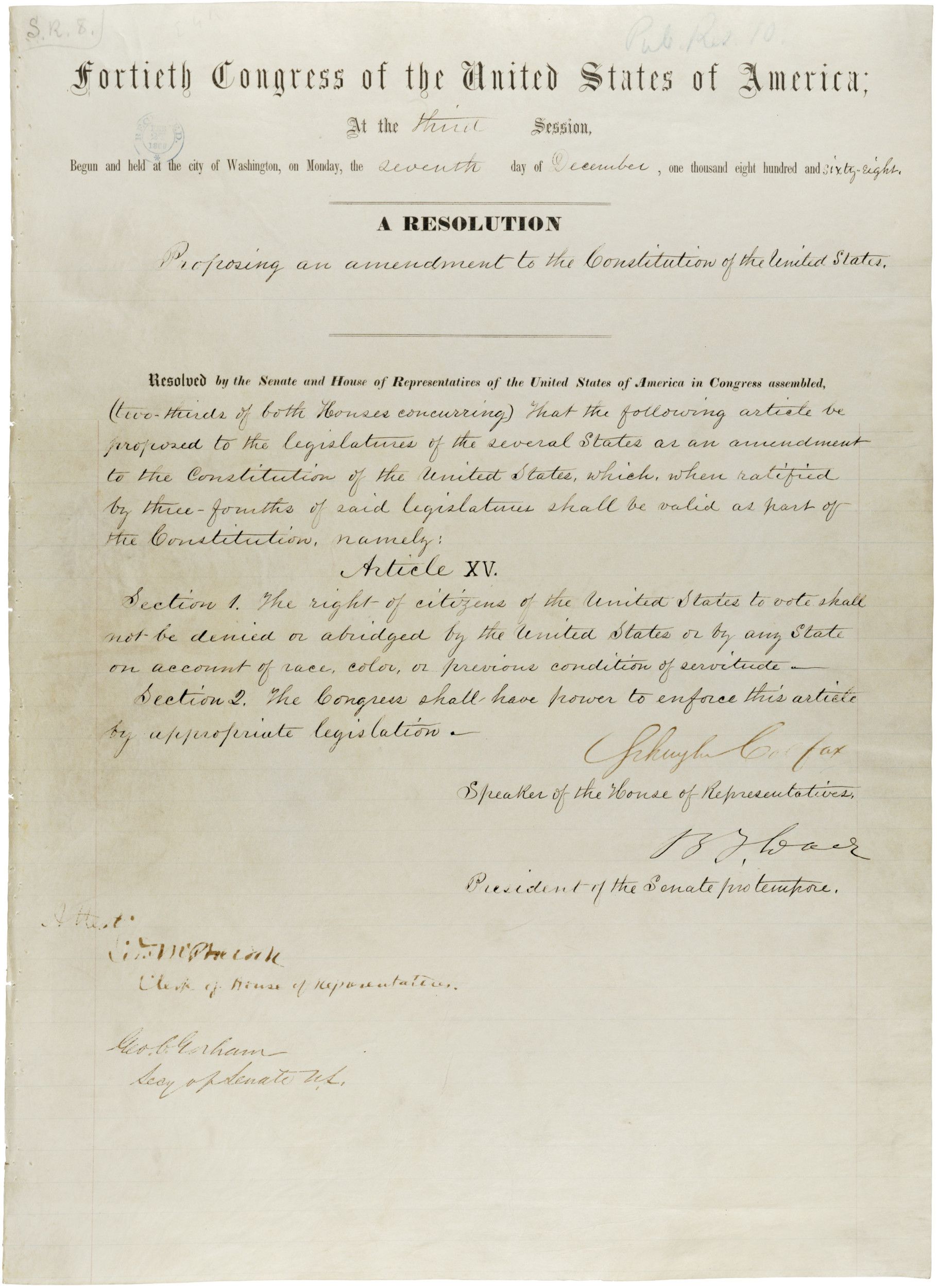

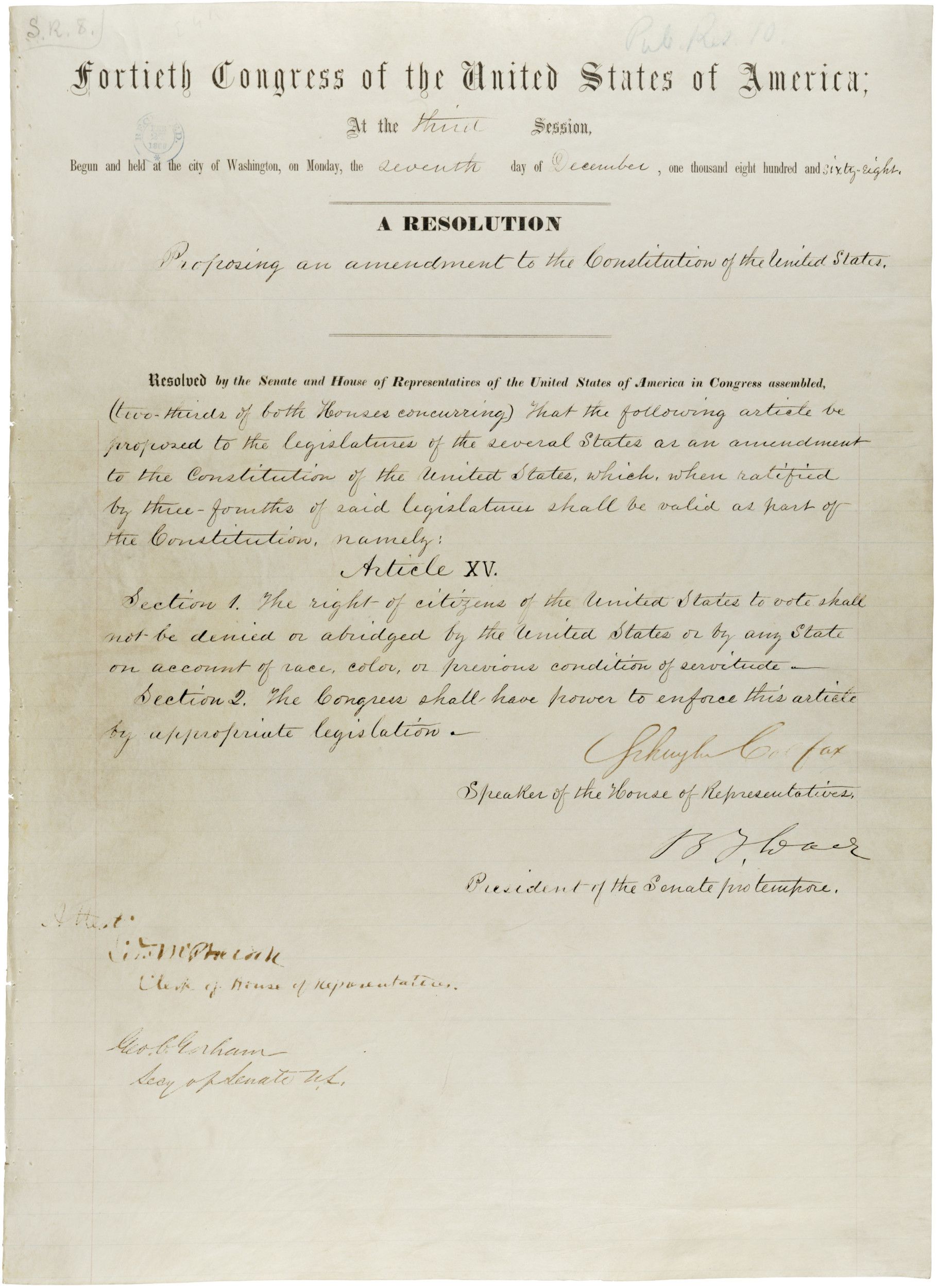

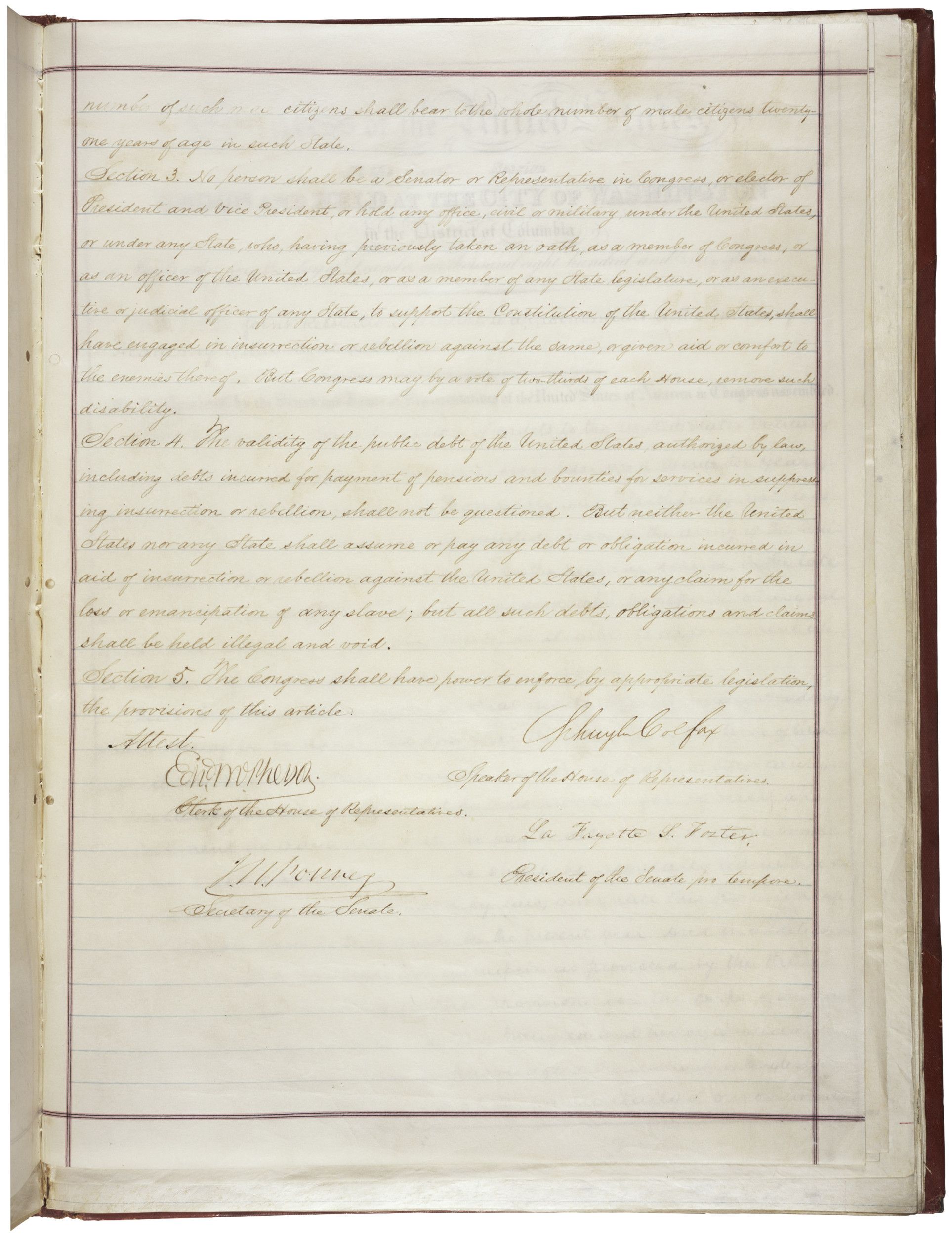

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Enter your response

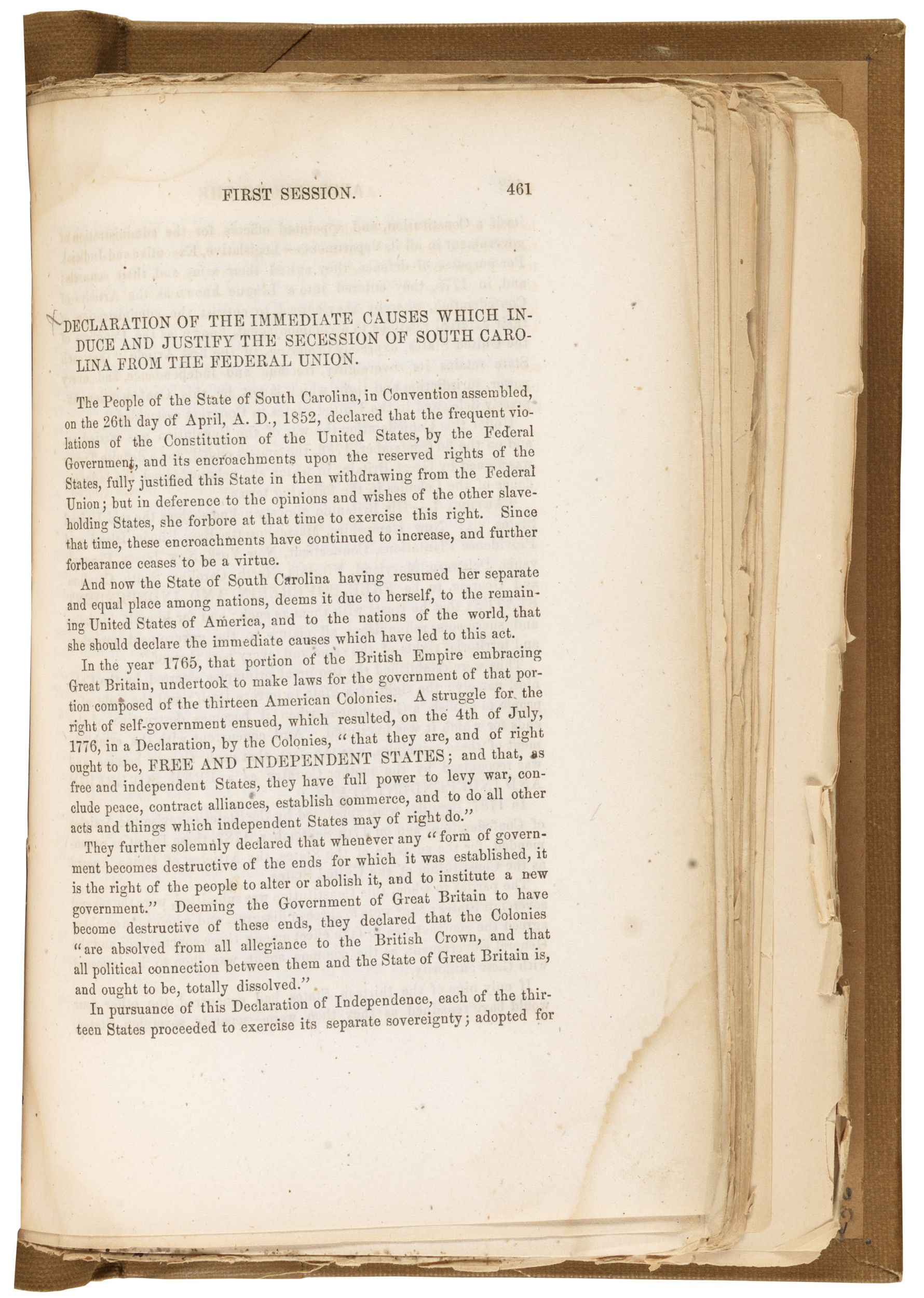

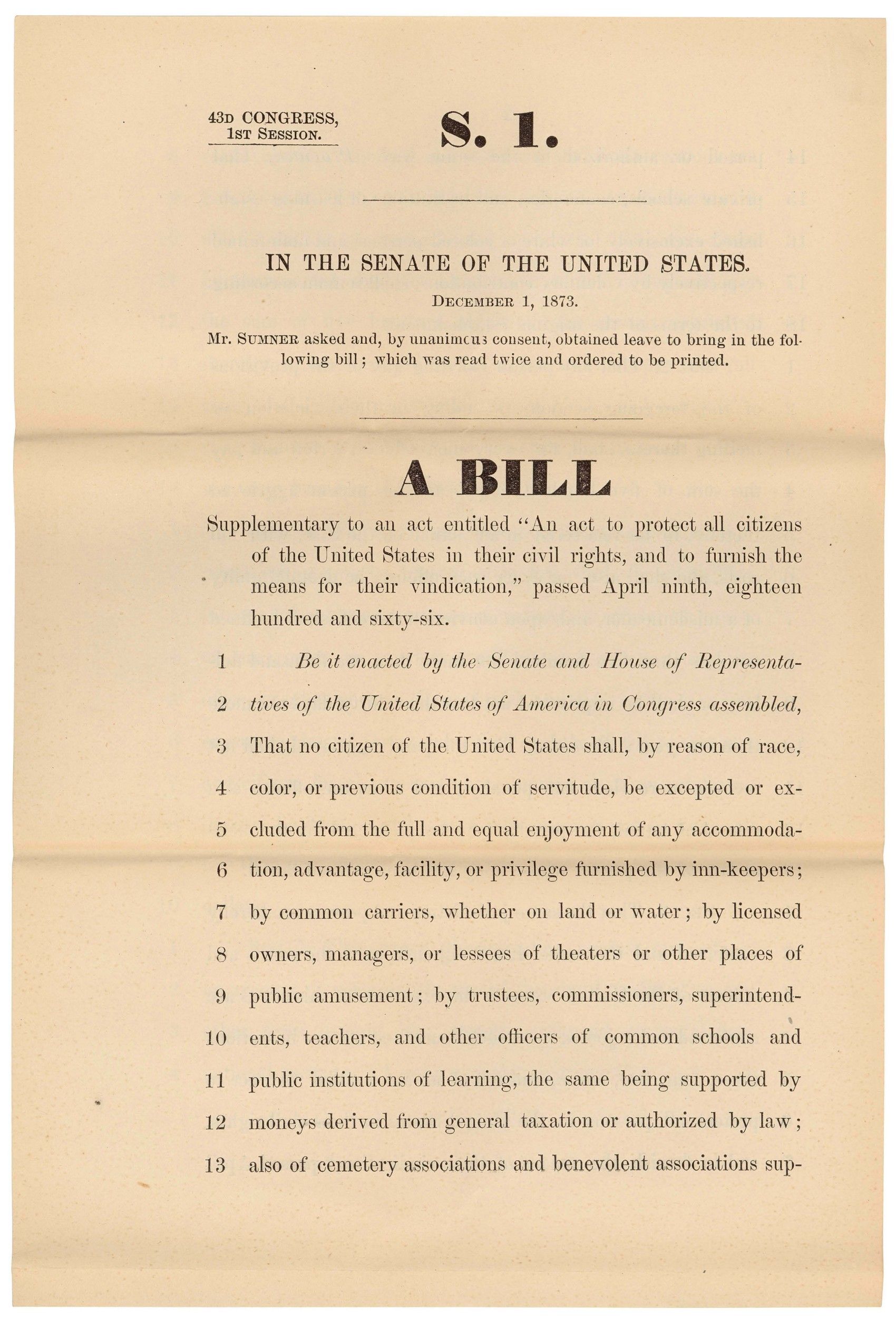

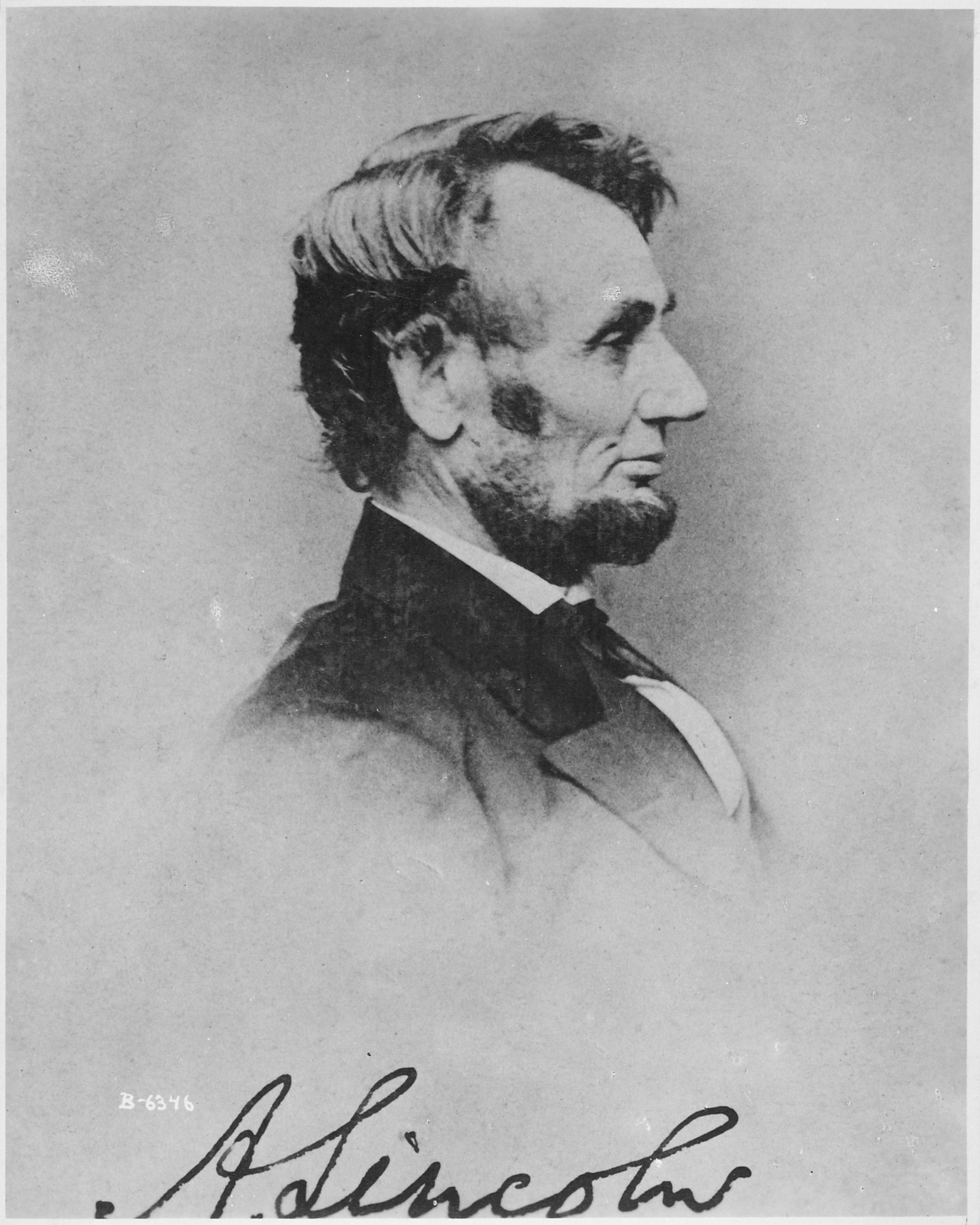

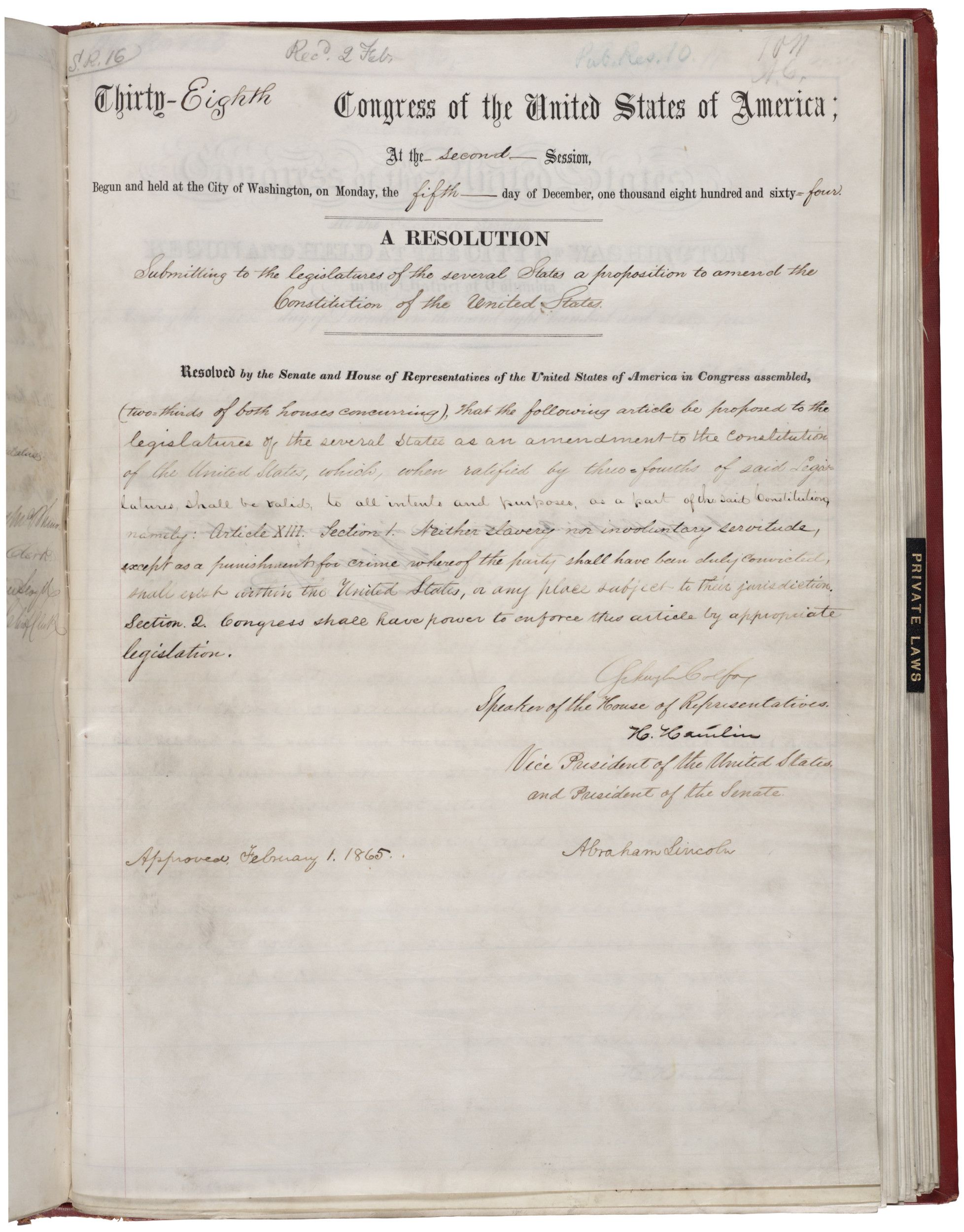

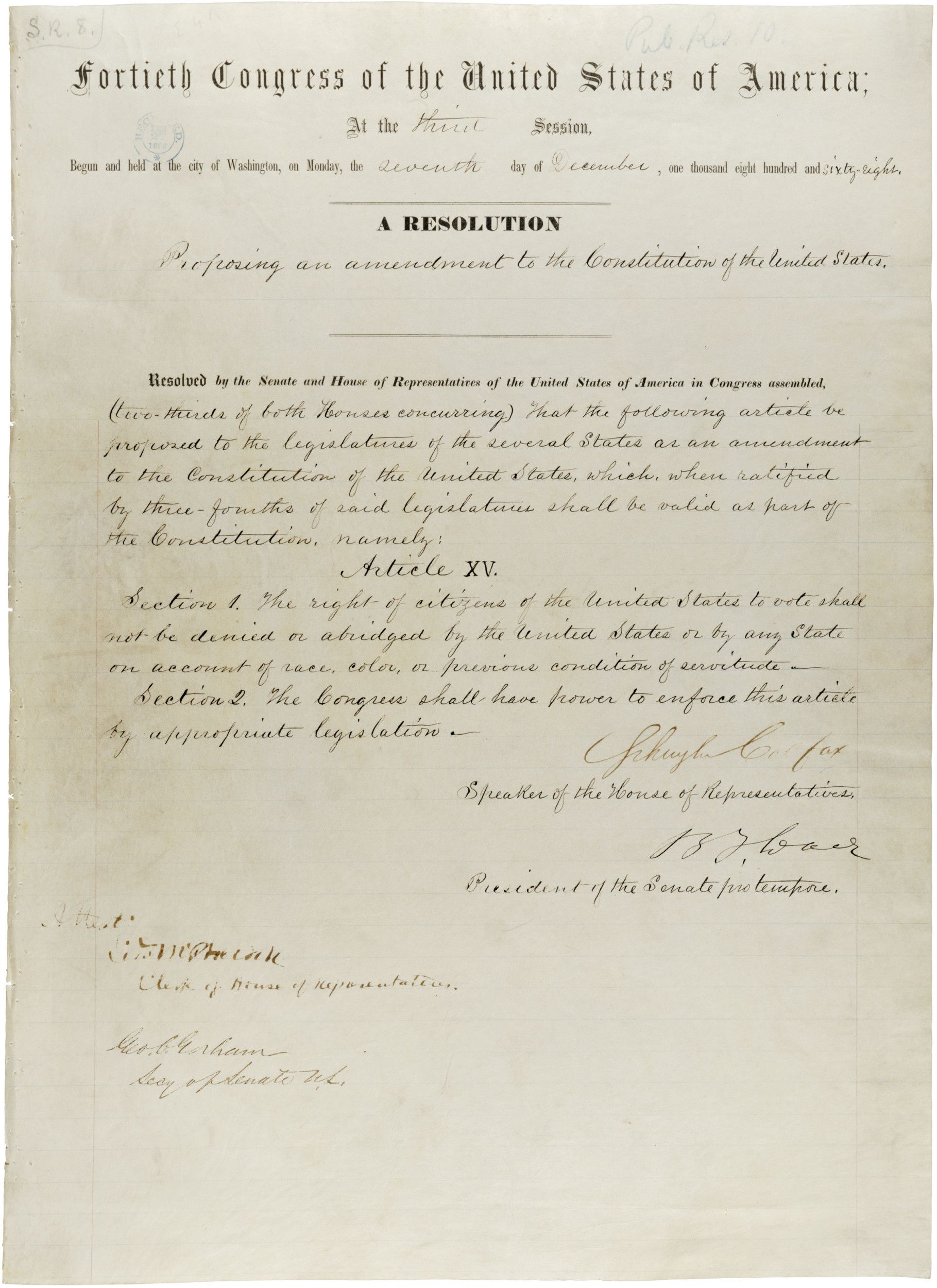

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

1

Activity Element

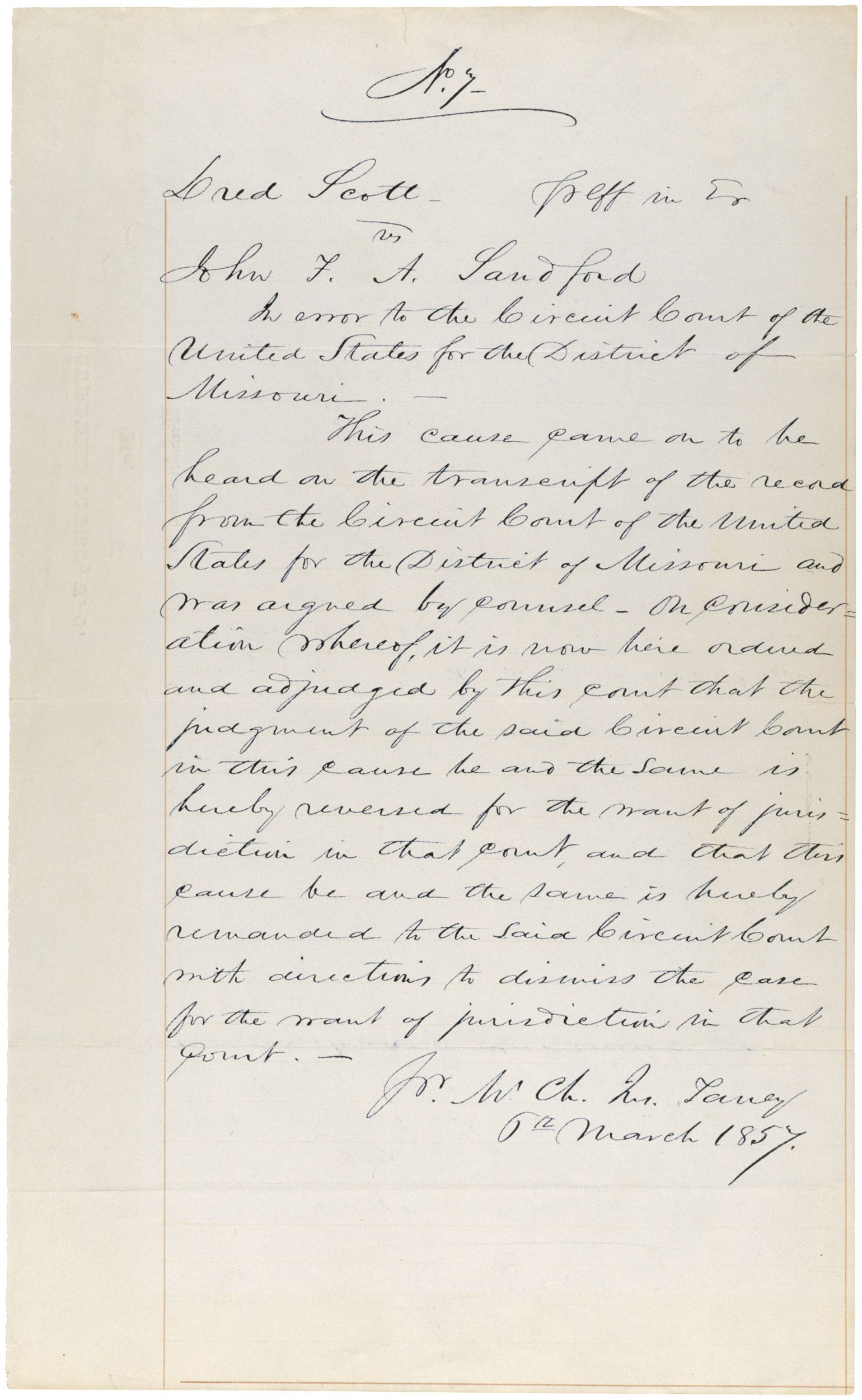

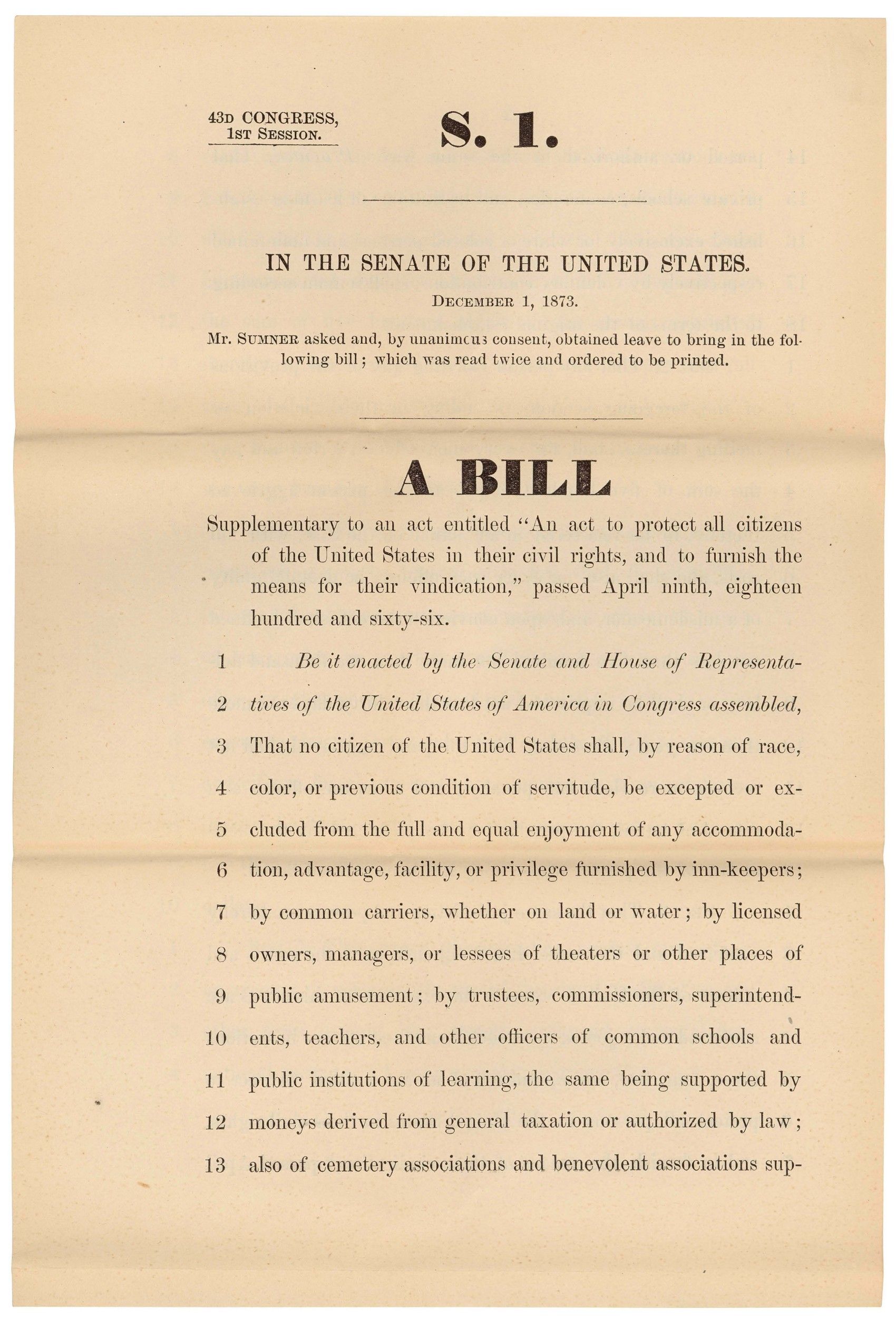

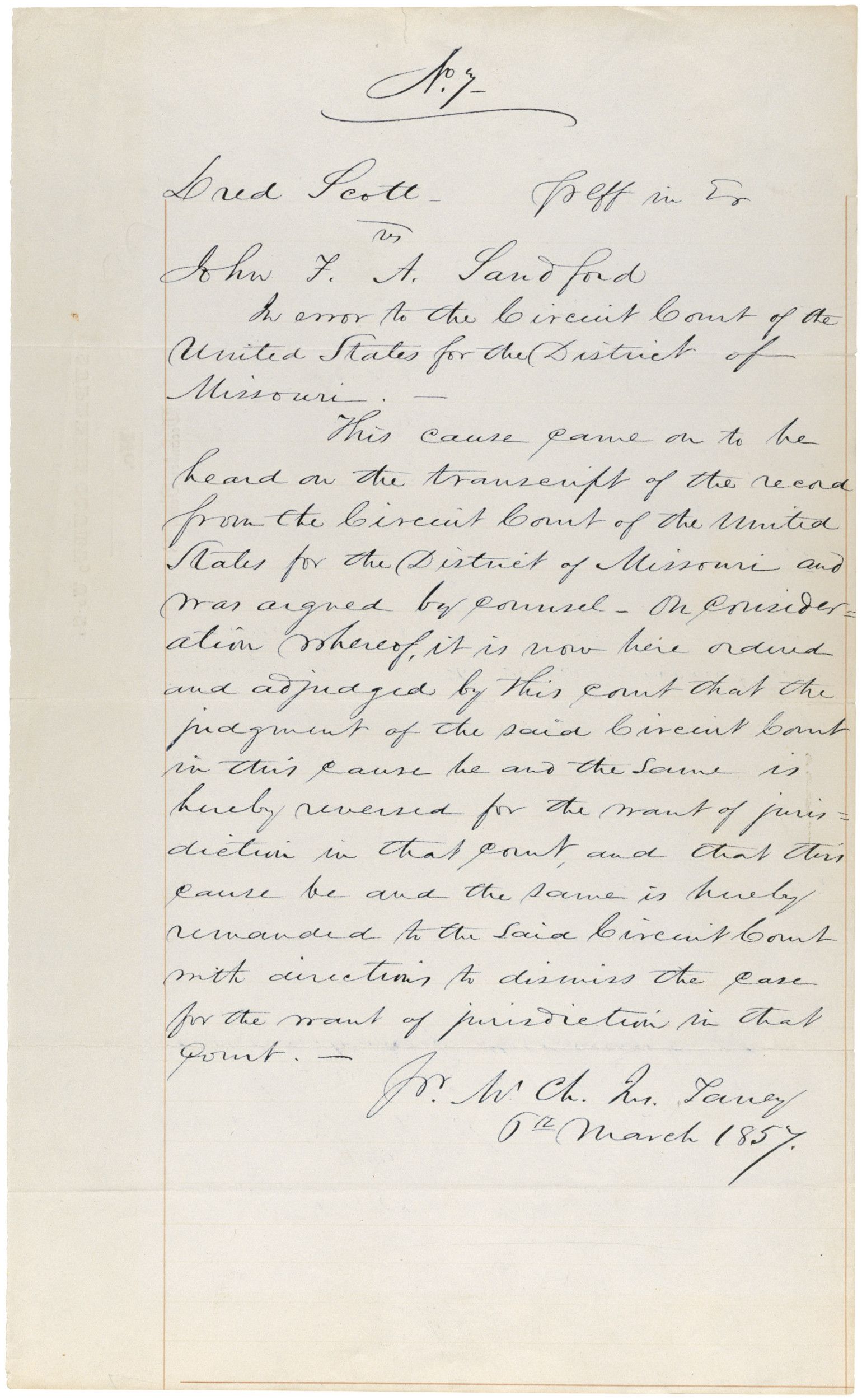

Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford

Page 1

2

Activity Element

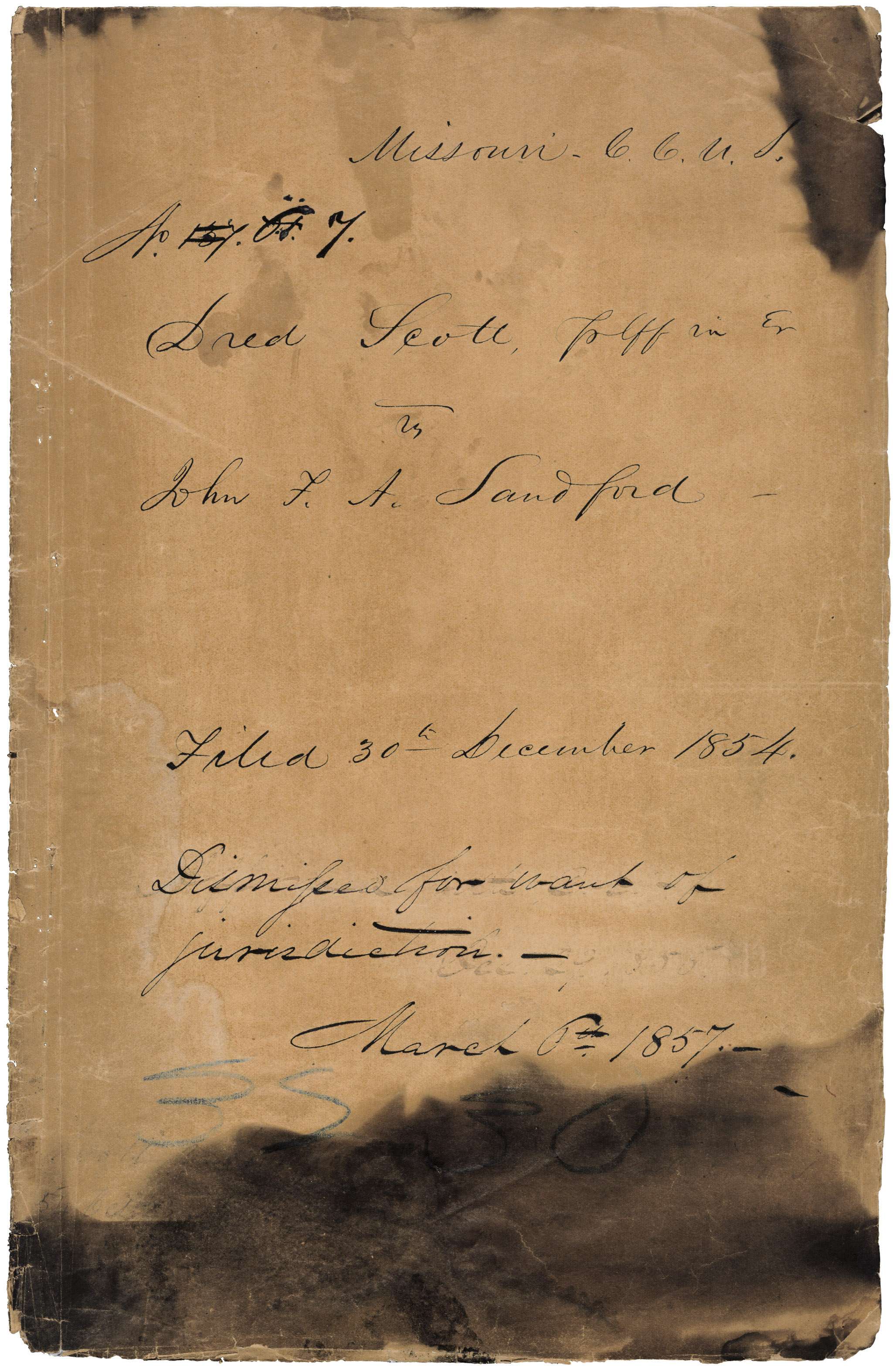

Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln

Page 1

3

Activity Element

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Page 1

4

Activity Element

Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

Page 2

5

Activity Element

Map of the Battle of the Antietam fought on the 16th and 17th September 1862 between the United States Forces under the Command of Maj. Genl. Geo. B. McClellan and the Confederates under Genl. Robt. E

Page 2

6

Activity Element

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 1

7

Activity Element

Photograph of United States Colored Troops at Port Hudson, Louisiana

Page 1

8

Activity Element

Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 2

9

Activity Element

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1

10

Activity Element

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1

11

Activity Element

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 1

Conclusion

From Dred Scott to the Civil Rights Act of 1875

Making Connections

The speed at which these changes took place was phenomenal considering how little change or social improvement African-Americans were able to make in the prior 250 years. This quick change was not well-received by others in the country. In 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court found the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional. And by the 1890s, many Southern states had either re-written or changed their state constitutions with unique ways to deny African-Americans the right to vote. Although the fight to retain them continued, these rights granted in the 1860s and 1870s were not strongly re-established until the 1960s and beyond.Select three documents (or the events they represent) from this activity that you consider to have had the most impact on the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th Century and compose a five-paragraph essay to support your argument.

Your Response

Document

Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford

3/6/1857

In this ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a federal territory.

In 1846, an enslaved Black man named Dred Scott and his wife, Harriet, had sued for their freedom in St. Louis Circuit Court. They claimed that they were free due to their residence in a free territory where slavery was prohibited.

The odds were in their favor. They had lived with their enslaver, an army surgeon, at Fort Snelling, then in the free Territory of Wisconsin. The Scotts' freedom could be established on the grounds that they had been held in bondage for extended periods in a free territory and were then returned to a slave state. Courts had ruled this way in the past.

However, what appeared to be a straightforward lawsuit between two private parties became an 11-year legal struggle that culminated in one of the most notorious decisions ever issued by the Supreme Court. Scott lost his case, which worked its way through the Missouri state courts; he then filed a new federal suit which ultimately reached the Supreme Court.

On its way to the Supreme Court, the Dred Scott case grew in scope and significance as slavery became the single most explosive issue in American politics. By the time the case reached the high Court, it had come to have enormous political implications for the entire nation. Slavery had become the single most explosive issue in American politics.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney read the majority opinion, which stated that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a federal territory. This decision moved the nation a step closer to the Civil War.

The decision in Scott v. Sandford, considered by many legal scholars to be the worst ever rendered by the Supreme Court, was overturned by the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and declared all persons born in the United States to be citizens of the United States.

In 1846, an enslaved Black man named Dred Scott and his wife, Harriet, had sued for their freedom in St. Louis Circuit Court. They claimed that they were free due to their residence in a free territory where slavery was prohibited.

The odds were in their favor. They had lived with their enslaver, an army surgeon, at Fort Snelling, then in the free Territory of Wisconsin. The Scotts' freedom could be established on the grounds that they had been held in bondage for extended periods in a free territory and were then returned to a slave state. Courts had ruled this way in the past.

However, what appeared to be a straightforward lawsuit between two private parties became an 11-year legal struggle that culminated in one of the most notorious decisions ever issued by the Supreme Court. Scott lost his case, which worked its way through the Missouri state courts; he then filed a new federal suit which ultimately reached the Supreme Court.

On its way to the Supreme Court, the Dred Scott case grew in scope and significance as slavery became the single most explosive issue in American politics. By the time the case reached the high Court, it had come to have enormous political implications for the entire nation. Slavery had become the single most explosive issue in American politics.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney read the majority opinion, which stated that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, could not expect any protection from the federal government or the courts. The opinion also stated that Congress had no authority to ban slavery from a federal territory. This decision moved the nation a step closer to the Civil War.

The decision in Scott v. Sandford, considered by many legal scholars to be the worst ever rendered by the Supreme Court, was overturned by the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution, which abolished slavery and declared all persons born in the United States to be citizens of the United States.

Transcript

Missouri - C. C. U. S.No. 7.

Dred Scott, Plff in Er

vs.

John F. A. Sandford

Filed 30th December 1854.

Dismissed for want of jurisdiction.

March 6th 1857

No. 7.

Dred Scott - Plff in Er

vs

John F. A. Sandford

In error to the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Missouri.

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the record from the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Missouri and was argued by counsel - on consideration whereof, it is now here ordered and adjudged by this court that the judgment of the said Circuit Court in this cause be and the same is hereby reversed for the want of jurisdiction in that court, and that this cause be and the same is hereby remanded to the said Circuit Court with directions to dismiss the case for the want of jurisdiction in that court.

Js. W. Ch. Mr. Taney

6th March 1857

This primary source comes from the Records of the Supreme Court of the United States.

National Archives Identifier: 301673

Full Citation: Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford; 3/6/1857; Dred Scott, Plaintiff in Error, v. John F. A. Sandford; Appellate Jurisdiction Case Files, 1792 - 2010; Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/dred-scott-judgment, April 19, 2024]Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford

Page 1

Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford

Page 2

Document

Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln

ca. 1860-1865

Shortly after being elected the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln faced a divided nation. The Civil War lasted almost his entire Presidency. Just weeks into his second term as President, Lincoln was assassinated while watching a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives Identifier: 530413

Full Citation: Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln; ca. 1860-1865 ; Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, 1921 - 1940; Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/photograph-of-president-abraham-lincoln, April 19, 2024]Photograph of President Abraham Lincoln

Page 1

Document

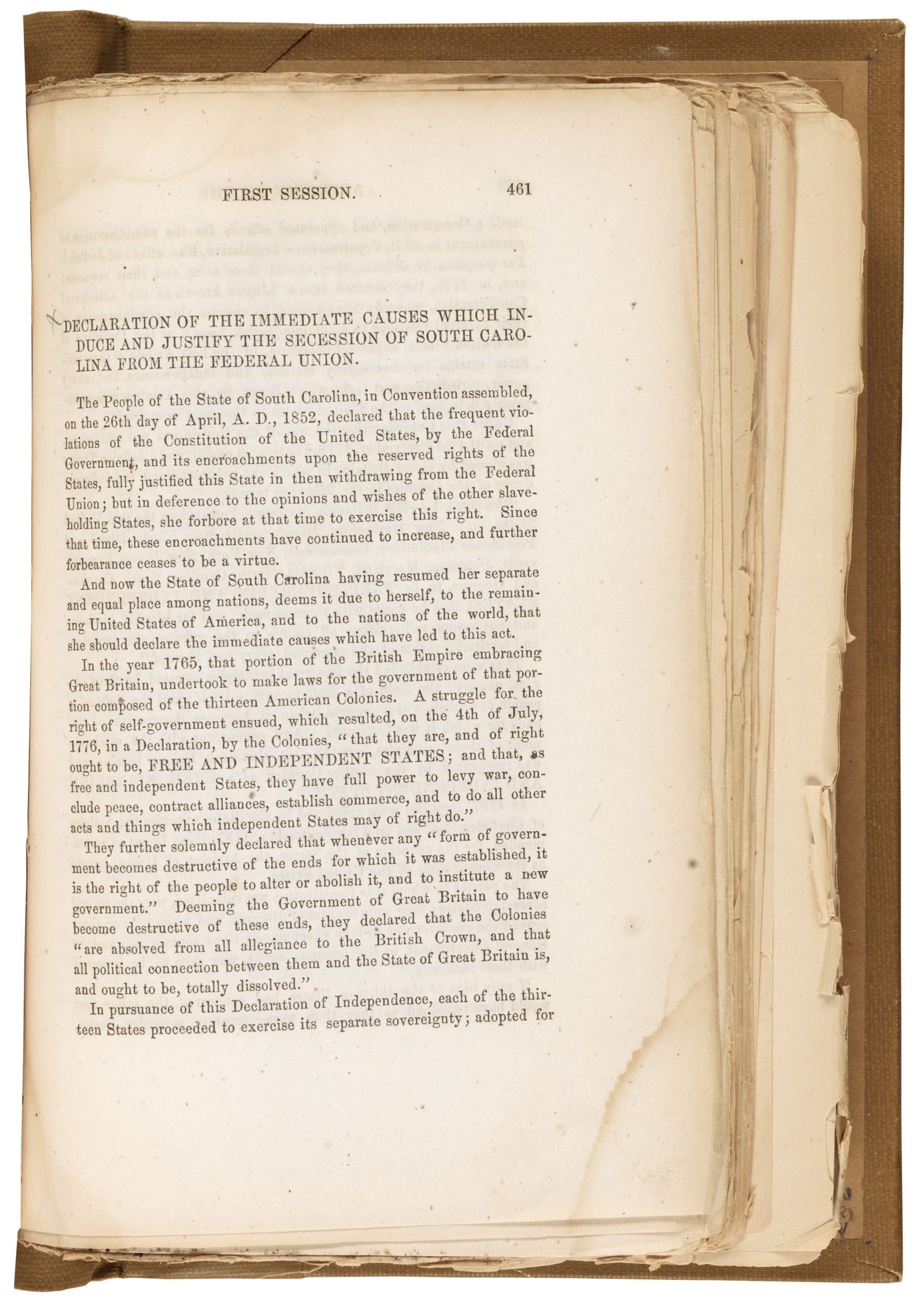

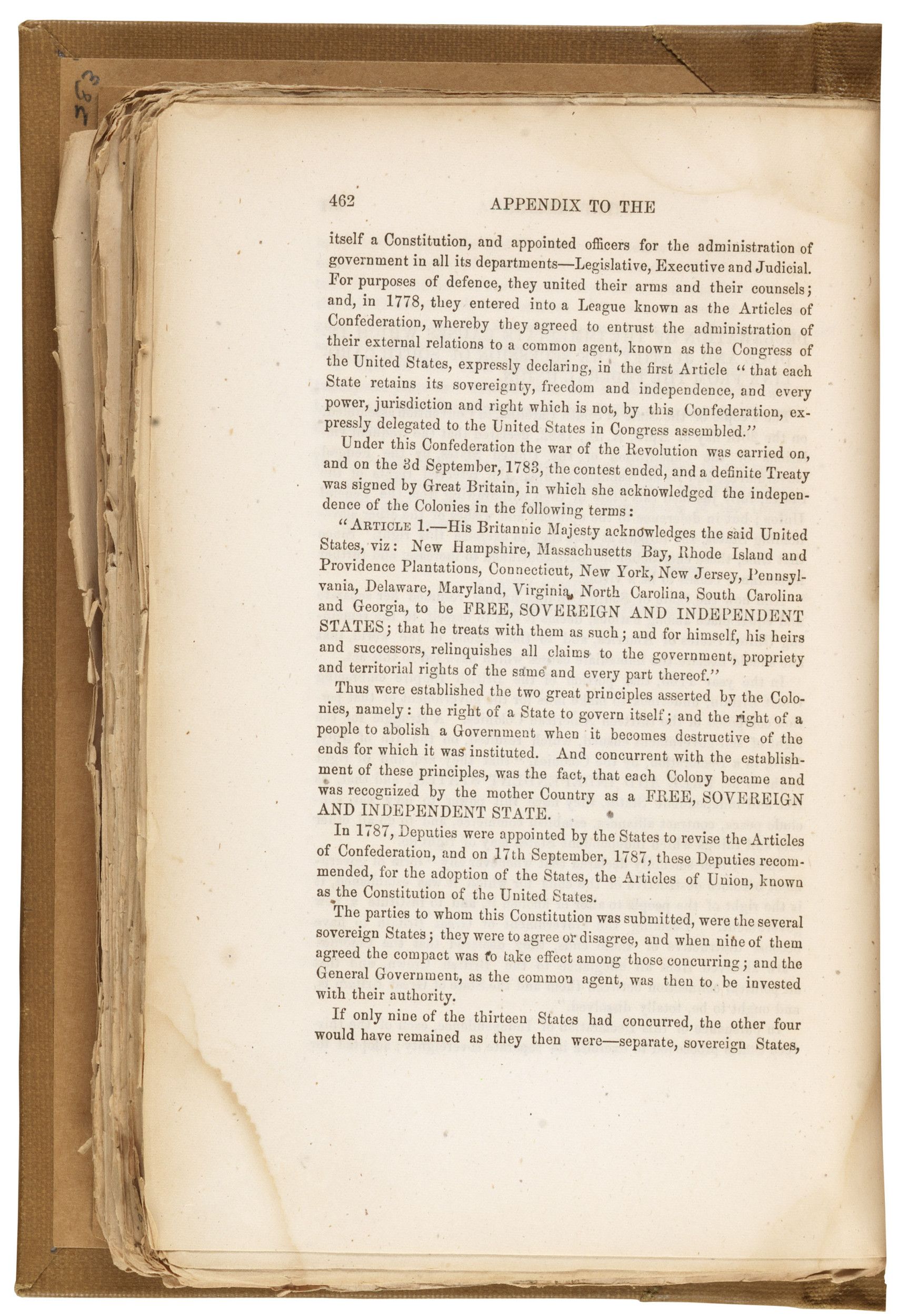

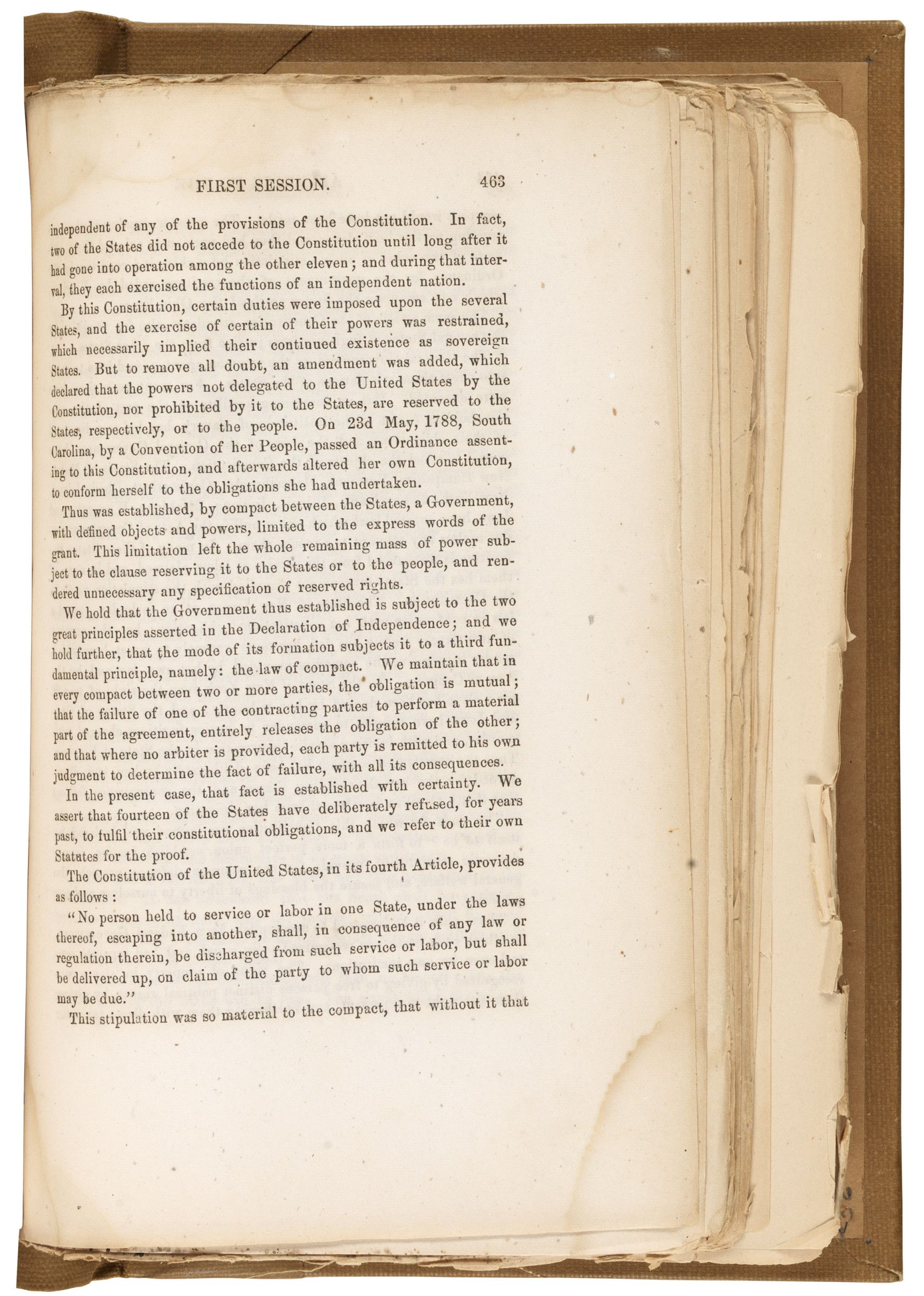

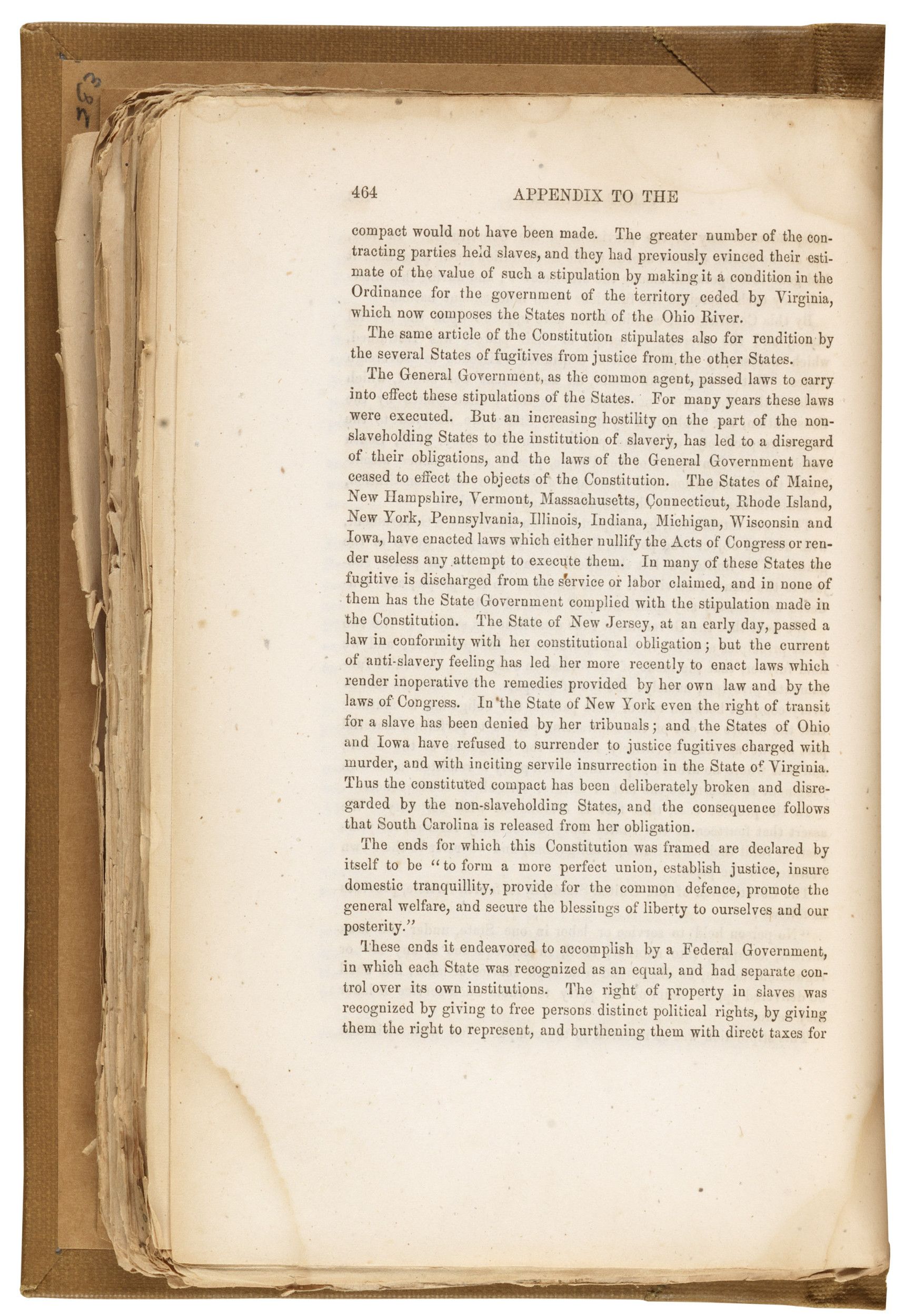

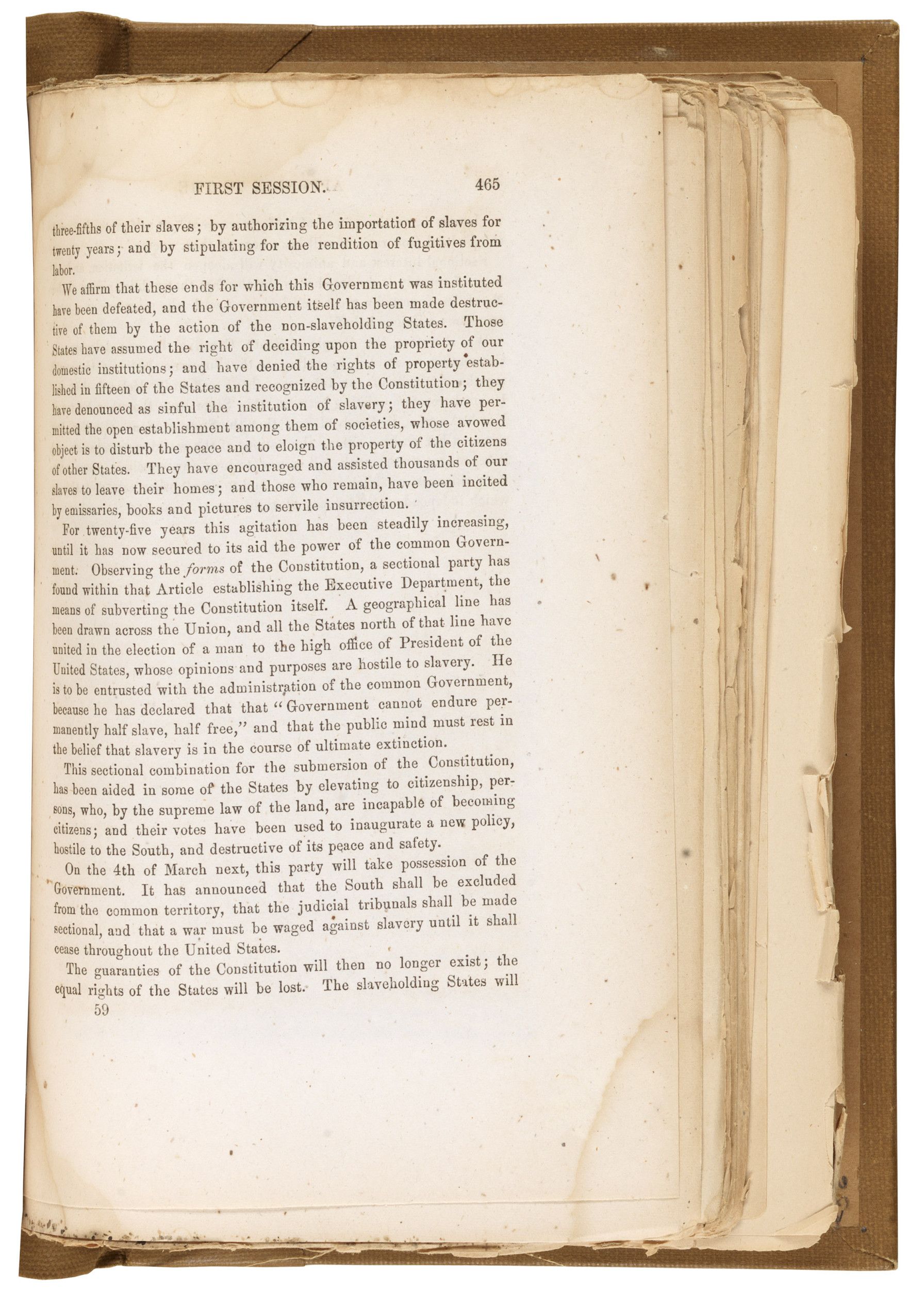

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

12/1860

This document outlines the stated reasons why the South Carolina state government separated from the United States of America, including the accusation that the Federal Government violated the U.S. Constitution and encroached upon the reserved rights of the States.

This primary source comes from the War Department Collection of Confederate Records.

National Archives Identifier: 3863809

Full Citation: Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union; 12/1860; War Department Collection of Confederate Records, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/declaration-of-immediate-causes-which-induce-and-justify-the-secession-of-south-carolina-from-the-federal-union, April 19, 2024]Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Page 1

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Page 2

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Page 3

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Page 4

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Page 5

Declaration of Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union

Page 6

Document

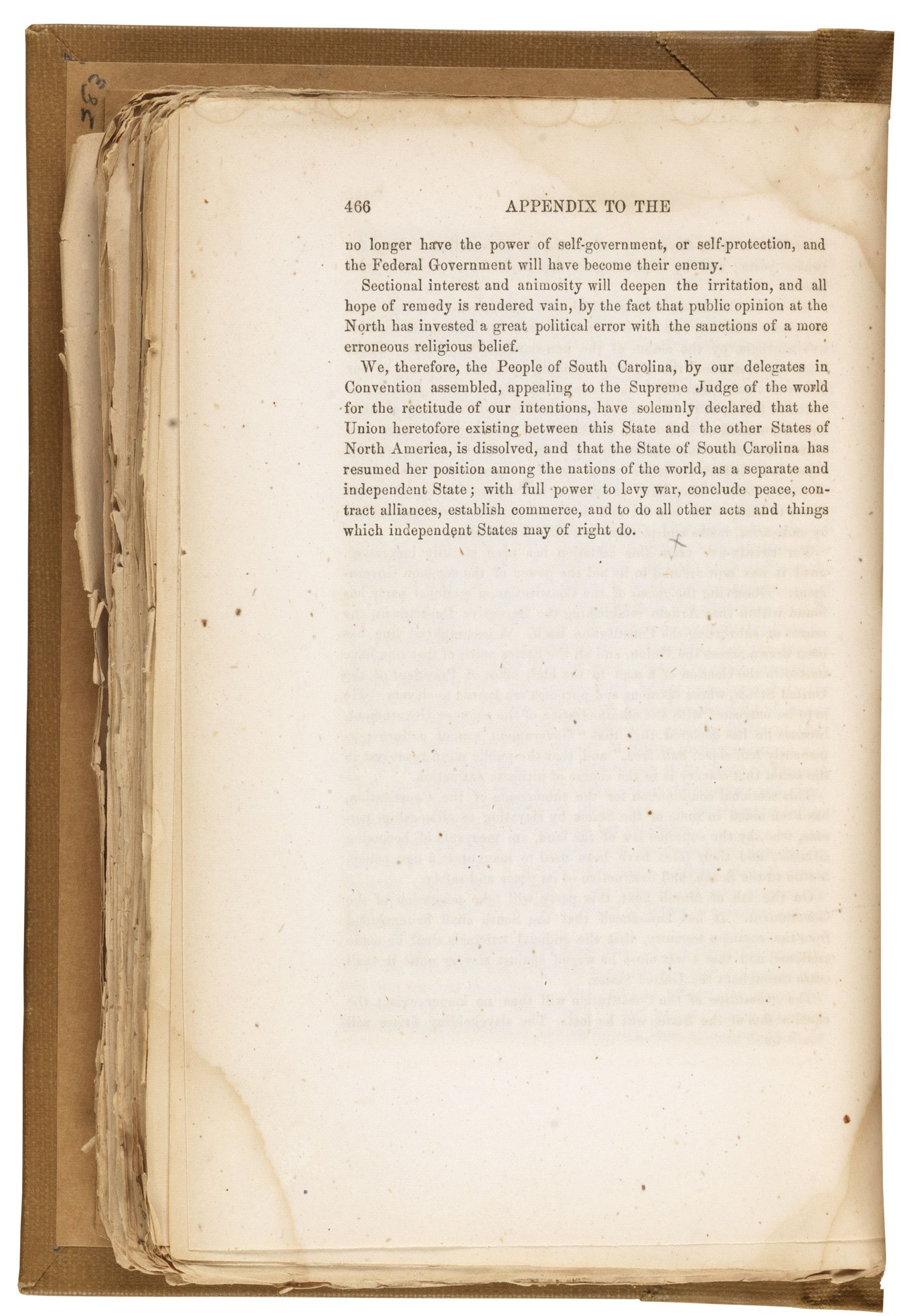

Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

3/2/1861

As southern states began seceding during the winter of 1860–61, several compromises were proposed to hold the nation together. One was a constitutional amendment that would have prevented Congress from passing legislation interfering with a state’s “domestic institutions . . . including that of persons held to labor or service.” Amendment sponsors hoped its approval would keep border states in the Union and reassure southerners that Republicans opposed only the extension, not the existence, of slavery. Congress approved the amendment, but only two state legislatures ratified it."

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 4688370

Full Citation: Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery; 3/2/1861; General Records of the United States Government, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/proposed-thirteenth-amendment-regarding-the-abolition-of-slavery, April 19, 2024]Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

Page 2

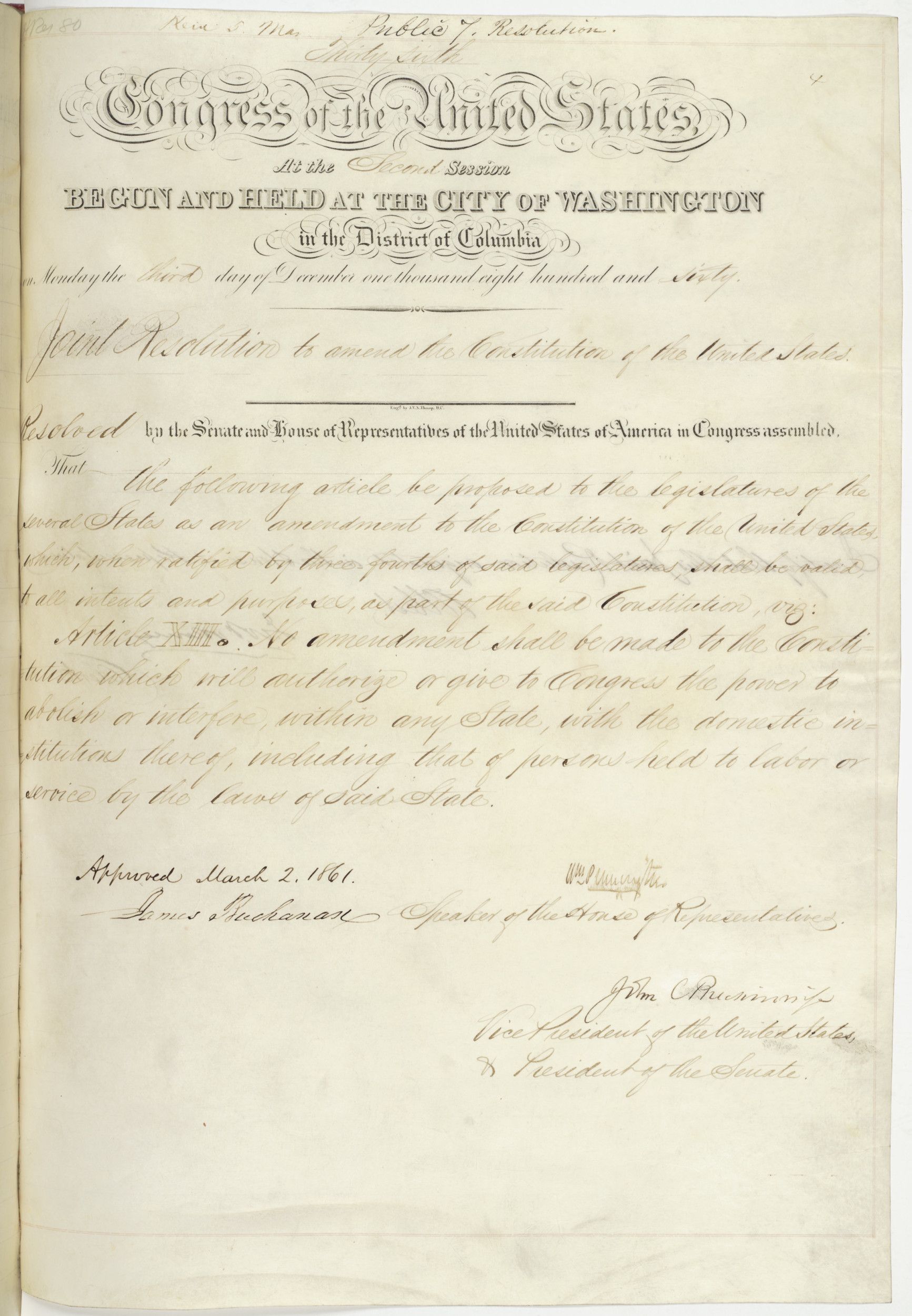

Document

Map of the Battle of the Antietam fought on the 16th and 17th September 1862 between the United States Forces under the Command of Maj. Genl. Geo. B. McClellan and the Confederates under Genl. Robt. E

10/1862

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers.

National Archives Identifier: 305578

Full Citation: Map of the Battle of the Antietam fought on the 16th and 17th September 1862 between the United States Forces under the Command of Maj. Genl. Geo. B. McClellan and the Confederates under Genl. Robt. E; 10/1862; Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/map-of-the-battle-of-the-antietam-fought-on-the-16th-and-17th-september-1862-between-the-united-states-forces-under-the-command-of-maj-genl-geo-b-mcclellan-and-the-confederates-under-genl-robt-e-lee, April 19, 2024]Map of the Battle of the Antietam fought on the 16th and 17th September 1862 between the United States Forces under the Command of Maj. Genl. Geo. B. McClellan and the Confederates under Genl. Robt. E

Page 2

Map of the Battle of the Antietam fought on the 16th and 17th September 1862 between the United States Forces under the Command of Maj. Genl. Geo. B. McClellan and the Confederates under Genl. Robt. E

Page 2

Document

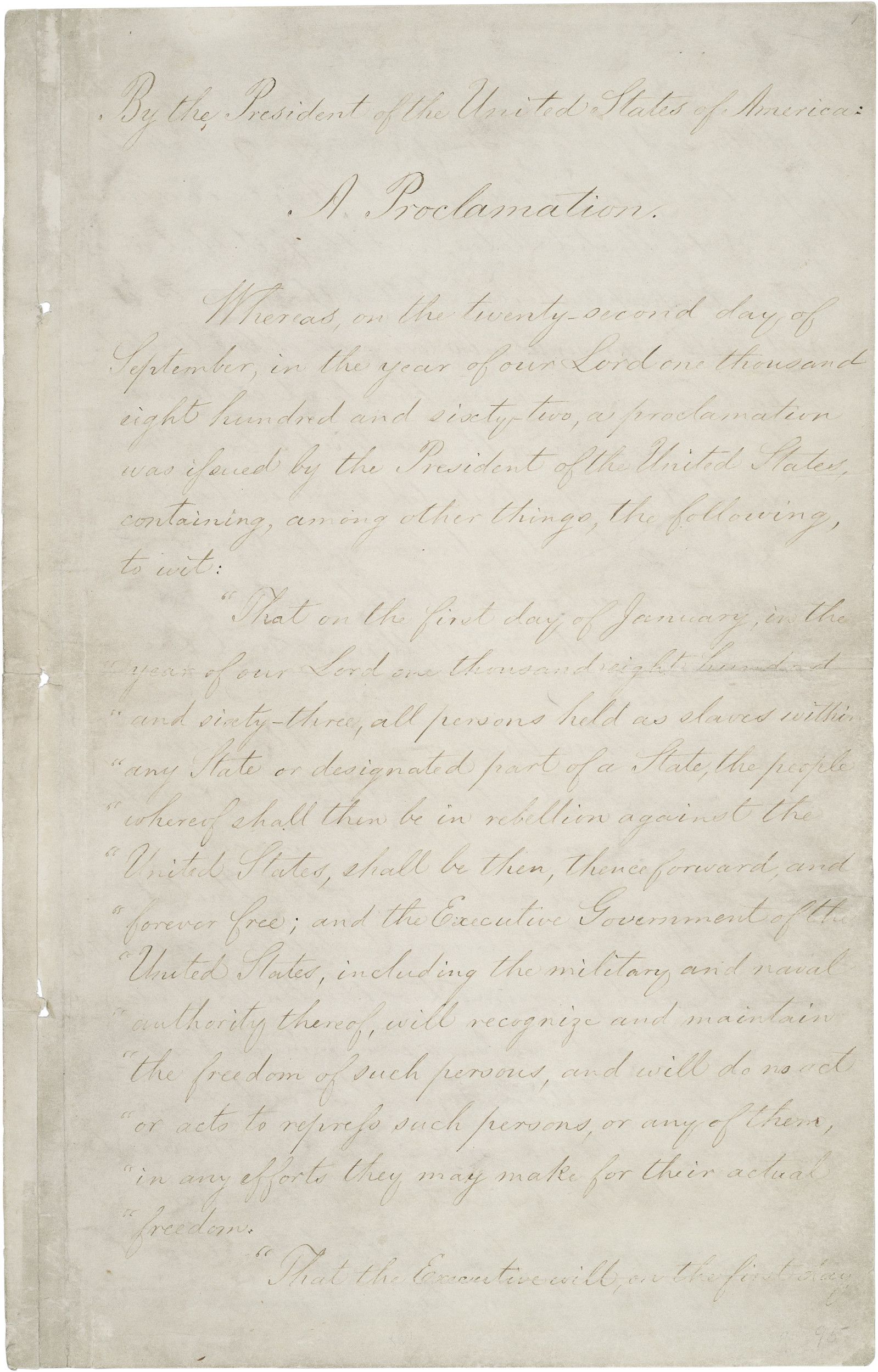

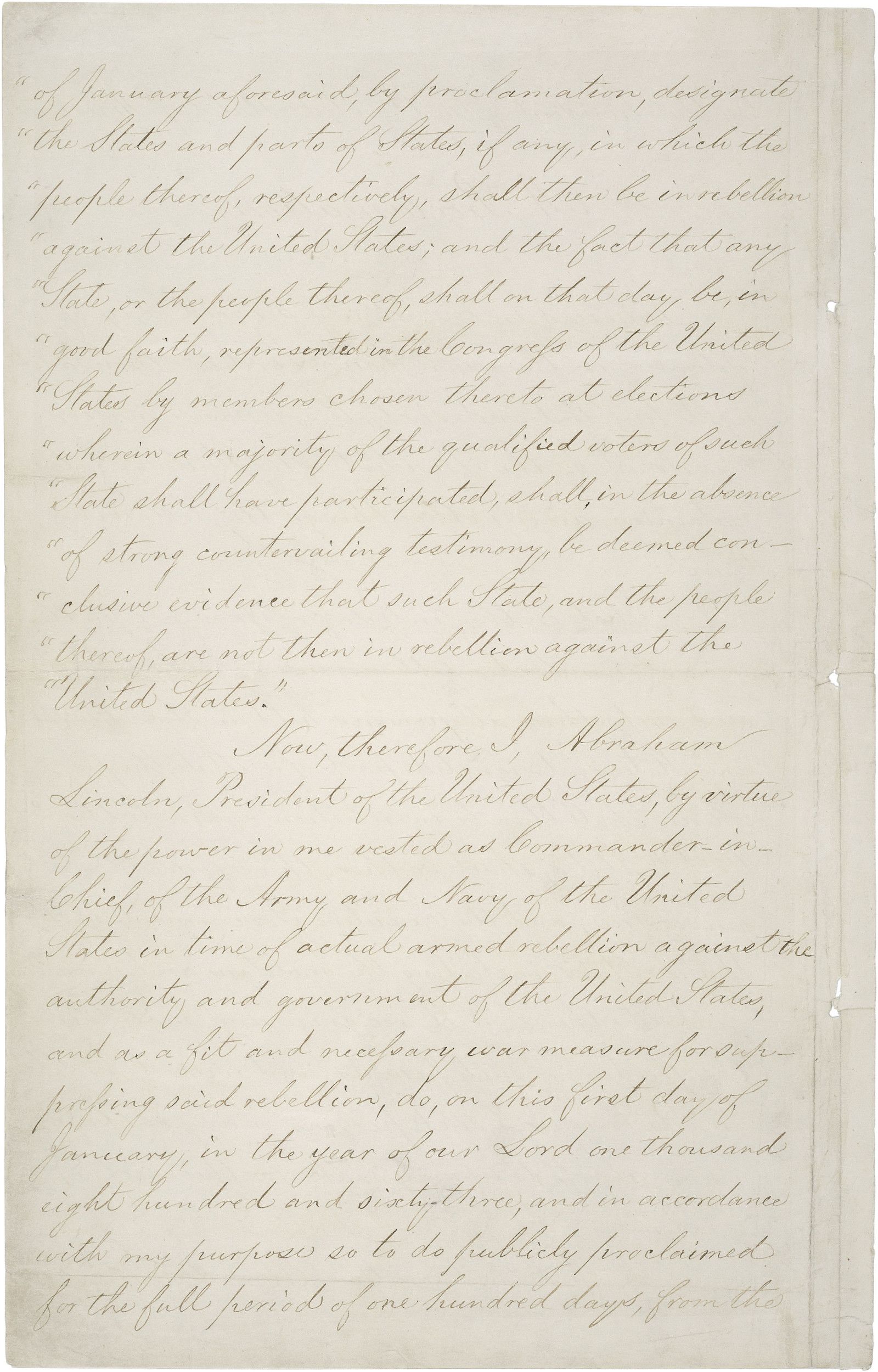

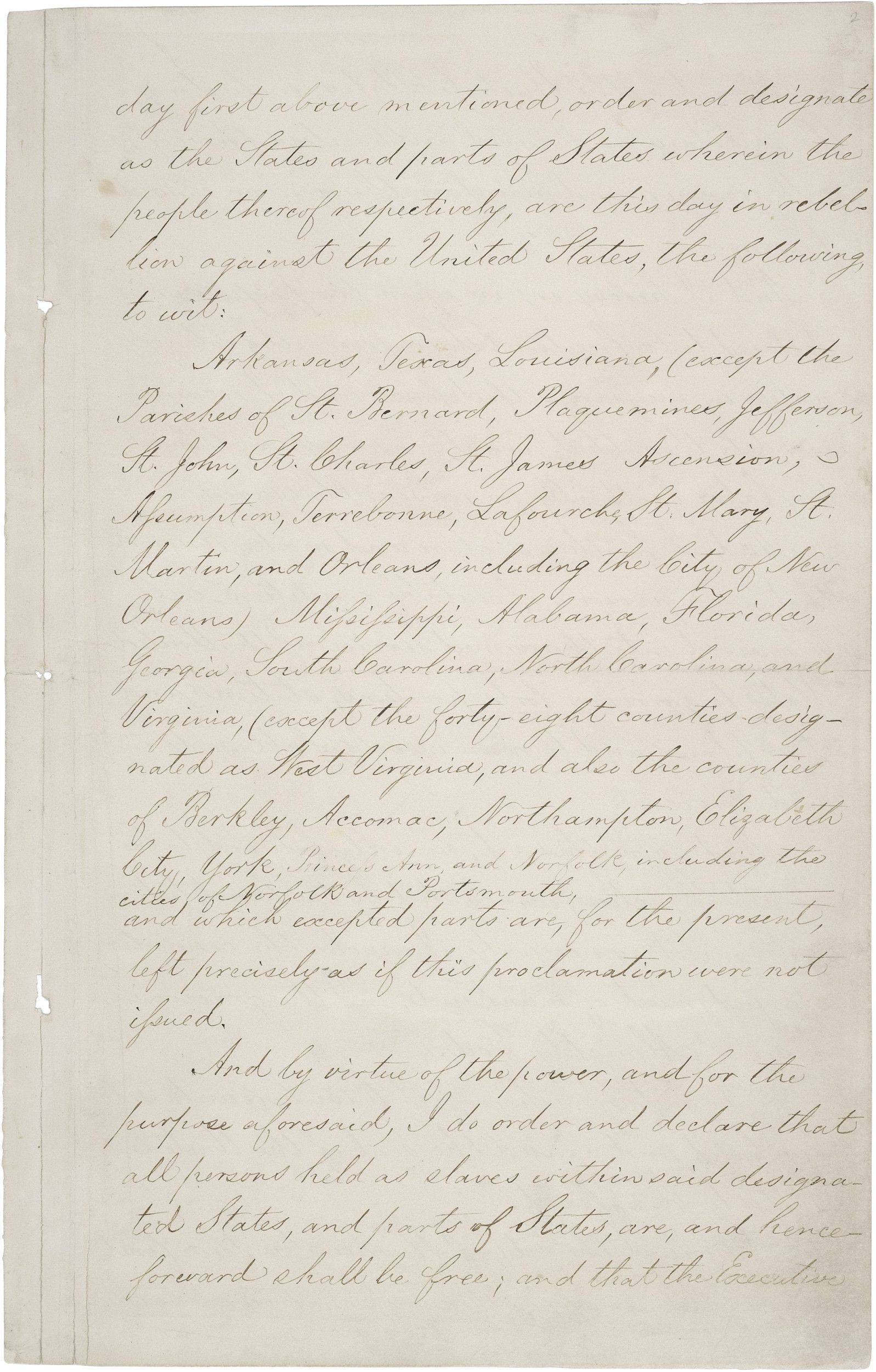

Emancipation Proclamation

1/1/1863

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, announcing, "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Initially, the Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that enslaved people in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free. One hundred days later, with the rebellion unabated, President issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Lincoln’s bold step to change the goals of the war was a military measure and came just a few days after the Union’s victory in the Battle of Antietam. With this Proclamation he hoped to inspire all Black people, and enslaved people in the Confederacy in particular, to support the Union cause and to keep England and France from giving political recognition and military aid to the Confederacy.

Because it was a military measure, however, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Union control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it did fundamentally transform the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of Federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of Black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 Black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

From the first days of the Civil War, enslaved people had acted to secure their own liberty. The Emancipation Proclamation confirmed their insistence that the war for the Union must become a war for freedom. It added moral force to the Union cause and strengthened the Union both militarily and politically. As a milestone along the road to slavery's final destruction, the Emancipation Proclamation has assumed a place among the great documents of human freedom.

Initially, the Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that enslaved people in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free. One hundred days later, with the rebellion unabated, President issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Lincoln’s bold step to change the goals of the war was a military measure and came just a few days after the Union’s victory in the Battle of Antietam. With this Proclamation he hoped to inspire all Black people, and enslaved people in the Confederacy in particular, to support the Union cause and to keep England and France from giving political recognition and military aid to the Confederacy.

Because it was a military measure, however, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Union control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it did fundamentally transform the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of Federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of Black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 Black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

From the first days of the Civil War, enslaved people had acted to secure their own liberty. The Emancipation Proclamation confirmed their insistence that the war for the Union must become a war for freedom. It added moral force to the Union cause and strengthened the Union both militarily and politically. As a milestone along the road to slavery's final destruction, the Emancipation Proclamation has assumed a place among the great documents of human freedom.

Transcript

By the President of the United States of America:A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States."

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 299998

Full Citation: Emancipation Proclamation; 1/1/1863; Presidential Proclamations, 1791 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/emancipation-proclamation, April 19, 2024]Emancipation Proclamation

Page 1

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 2

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 3

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 4

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 5

Document

Photograph of United States Colored Troops at Port Hudson, Louisiana

1864

Tens of thousands of freedmen and runaway slaves served in the regiments of the United States Colored Troops and other state units. The men in this photograph, taken in 1864, were probably members of one of these units, the Corps d’Afrique. The Corps was organized in 1863 from men who served in Union General Benjamin Butler’s Louisiana Native Guard regiments.

This primary source comes from the Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs.

National Archives Identifier: 594179

Full Citation: Photograph of United States Colored Troops at Port Hudson, Louisiana; 1864; Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, . [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/usct-port-hudson, April 19, 2024]Photograph of United States Colored Troops at Port Hudson, Louisiana

Page 1

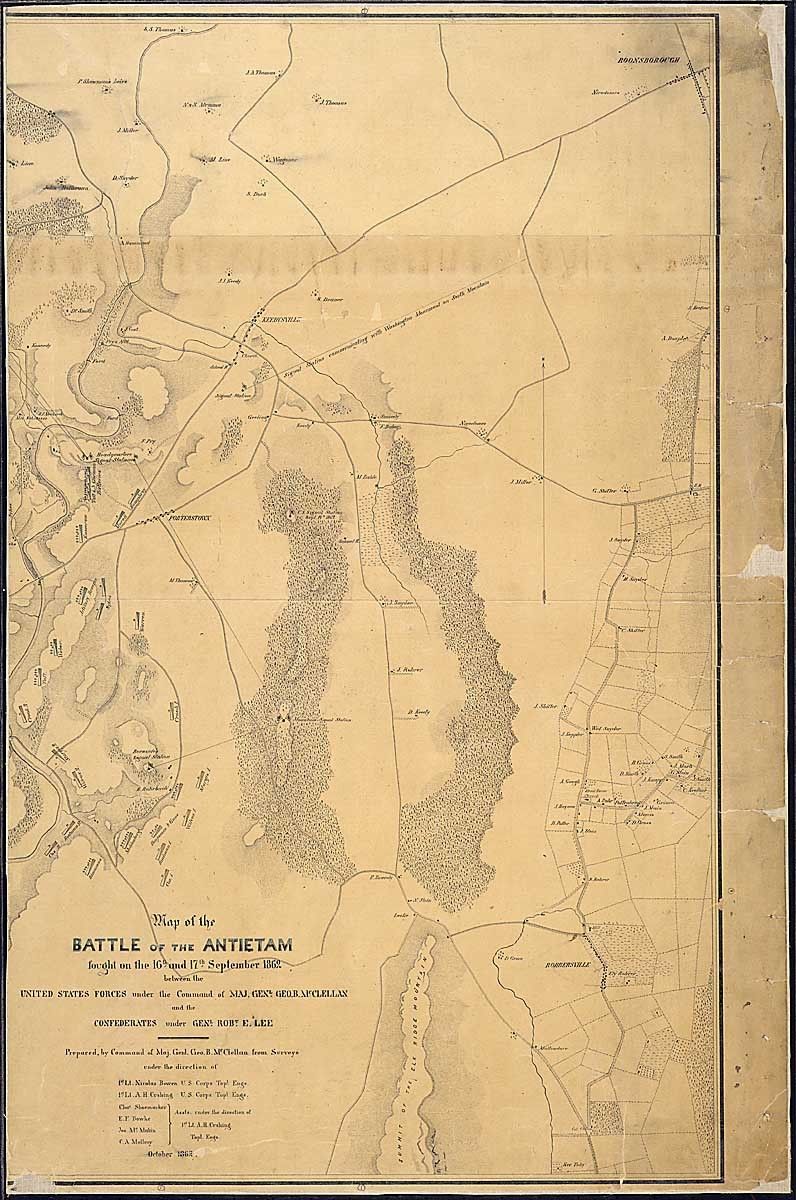

Document

Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

1/31/1865

This is a draft of a joint resolution proposing the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution that started in the Senate. A joint resolution is a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification. This particular resolution became the 13th Amendment, ending slavery in the United States in 1865.

In 1863, President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Nonetheless, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation since it only applied to areas of the Confederacy currently in a state of rebellion (and not even to the loyal “border states” that remained in the Union). Lincoln recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

The 13th Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War before the Southern states had been restored to the Union, and should have easily passed in Congress. However, though the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through Congress. He insisted that passage of the 13th Amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming 1864 Presidential election. His efforts met with success when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119–56.

On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. The necessary number of states (three-fourths) ratified it by December 6, 1865. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery. The 13th Amendment, along with the 14th and 15th, is one of the trio of Civil War amendments that greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans.

In 1863, President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Nonetheless, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation since it only applied to areas of the Confederacy currently in a state of rebellion (and not even to the loyal “border states” that remained in the Union). Lincoln recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

The 13th Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War before the Southern states had been restored to the Union, and should have easily passed in Congress. However, though the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through Congress. He insisted that passage of the 13th Amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming 1864 Presidential election. His efforts met with success when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119–56.

On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. The necessary number of states (three-fourths) ratified it by December 6, 1865. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery. The 13th Amendment, along with the 14th and 15th, is one of the trio of Civil War amendments that greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans.

Transcript

Thirty-Eighth Congress of the United StatesAt the Second Session

Begun and held at the City of Washington, on Monday, the fifth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four

A Resolution

Submitting to the legislatures of the several States a proposition to amend the Constitution of the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

(two-thirds of both houses concurring), that the following article be proposed to the legislatures of the several states as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said Legislatures shall be

valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the said Constitution, namely: Article XIII. Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Schuyler Colfax

Speaker of the House of Representatives

Hannibal Hamlin

Vice President of the United States

and President of the Senate

Approved February 1, 1865 Abraham Lincoln

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 1408764

Full Citation: Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; 1/31/1865; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/thirteenth-amendment, April 19, 2024]Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 2

Document

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

6/13/1866

Passed by Congress June 13, 1866, and ratified July 9, 1868, the 14th amendment guarantees rights of citizenship, due process, and equal protection under the law to all citizens. This document is the joint resolution – a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch – proposing the amendment. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification.

Following the Civil War, Congress submitted to the states three amendments as part of its Reconstruction program to guarantee equal civil and legal rights to Black citizens. A major provision of the 14th amendment was to grant citizenship to “All persons born or naturalized in the United States,” thereby granting citizenship to formerly enslaved people.

Another equally important provision was the statement that “nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The right to due process of law and equal protection of the law now applied to both the federal and state governments.

On June 16, 1866, the House Joint Resolution proposing the 14th amendment to the Constitution was submitted to the states. On July 28, 1868, the 14th amendment was declared, in a certificate of the Secretary of State, ratified by the necessary 28 of the 37 States (three-fourths of states), and became part of the supreme law of the land.

Congressman John A. Bingham of Ohio, the primary author of the first section of the 14th amendment, intended that the amendment also nationalize the Bill of Rights by making it binding upon the states. When introducing the amendment, Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan specifically stated that the privileges and immunities clause would extend to the states “the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendments.” Historians disagree on how widely Bingham's and Howard's views were shared at the time in the Congress, or across the country in general. No one in Congress explicitly contradicted their view of the Amendment, but only a few members said anything at all about its meaning on this issue. For many years, the Supreme Court ruled that the amendment did not extend the Bill of Rights to the states.

Not only did the 14th amendment fail to extend the Bill of Rights to the states; it also failed to protect the rights of Black citizens. A legacy of Reconstruction was the determined struggle of Black and white citizens to make the promise of the 14th amendment a reality. Citizens petitioned and initiated court cases, Congress enacted legislation, and the executive branch attempted to enforce measures that would guard all citizens’ rights. While these citizens did not succeed in empowering the 14th amendment during the Reconstruction, they effectively articulated arguments and offered dissenting opinions that would be the basis for change in the 20th century.

Following the Civil War, Congress submitted to the states three amendments as part of its Reconstruction program to guarantee equal civil and legal rights to Black citizens. A major provision of the 14th amendment was to grant citizenship to “All persons born or naturalized in the United States,” thereby granting citizenship to formerly enslaved people.

Another equally important provision was the statement that “nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The right to due process of law and equal protection of the law now applied to both the federal and state governments.

On June 16, 1866, the House Joint Resolution proposing the 14th amendment to the Constitution was submitted to the states. On July 28, 1868, the 14th amendment was declared, in a certificate of the Secretary of State, ratified by the necessary 28 of the 37 States (three-fourths of states), and became part of the supreme law of the land.

Congressman John A. Bingham of Ohio, the primary author of the first section of the 14th amendment, intended that the amendment also nationalize the Bill of Rights by making it binding upon the states. When introducing the amendment, Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan specifically stated that the privileges and immunities clause would extend to the states “the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendments.” Historians disagree on how widely Bingham's and Howard's views were shared at the time in the Congress, or across the country in general. No one in Congress explicitly contradicted their view of the Amendment, but only a few members said anything at all about its meaning on this issue. For many years, the Supreme Court ruled that the amendment did not extend the Bill of Rights to the states.

Not only did the 14th amendment fail to extend the Bill of Rights to the states; it also failed to protect the rights of Black citizens. A legacy of Reconstruction was the determined struggle of Black and white citizens to make the promise of the 14th amendment a reality. Citizens petitioned and initiated court cases, Congress enacted legislation, and the executive branch attempted to enforce measures that would guard all citizens’ rights. While these citizens did not succeed in empowering the 14th amendment during the Reconstruction, they effectively articulated arguments and offered dissenting opinions that would be the basis for change in the 20th century.

Transcript

Article XIVSection 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the

number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Section 3. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section 4. The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section 5. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 1408913

Full Citation: Joint Resolution Proposing the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; 6/13/1866; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/fourteenth-amendment, April 19, 2024]Joint Resolution Proposing the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 2

Document

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

2/26/1869

Passed by Congress on February 26, 1869, and ratified February 3, 1870, the 15th amendment granted African-American men the right to vote: the right of male U.S. citizens to vote shall not be denied or abridged “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This document is the joint resolution – a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch – proposing the amendment. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the 15th amendment appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the 13th amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the 14th amendment, Black males were given the vote by the 15th amendment.

African Americans voted and held office in many Southern states through the 1880s, but in the early 1890s, steps were taken to ensure subsequent “white supremacy.” The 15th Amendment had been carefully worded to maximize its chances of ratification. It didn't go so far as to grant the right to vote to all citizens regardless of race —instead, it barred states from denying suffrage based on race, opening a loophole for literacy, land ownership, or other requirements. It was a loophole that Southern states quickly exploited to effectively ban Black people from the polls.

Literacy tests for the vote, “grandfather clauses” excluding those whose ancestors had not voted in the 1860s, and other devices to disenfranchise African Americans were written into the laws of former Confederate states.

Social and economic segregation were added to Black America’s loss of political power. In 1896, the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson legalized “separate but equal” facilities for the races. For more than 50 years, the overwhelming majority of African American citizens were reduced to second-class citizenship under the “Jim Crow” segregation system.

During that time, African Americans sought to secure their rights and improve their position through organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) and the National Urban League, and through the individual efforts of reformers like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and A. Philip Randolph.

The most direct attack on the problem of African-American disfranchisement came in 1965. Prompted by reports of continuing discriminatory voting practices in many Southern states, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Congress to pass legislation “which will make it impossible to thwart the 15th amendment.” He reminded Congress that “we cannot have government for all the people until we first make certain it is government of and by all the people.”

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, extended in 1970, 1975, and 1982, abolished all remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorized federal supervision of voter registration where necessary. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the act involving federal oversight of voting rules in nine states.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the 15th amendment appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the 13th amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the 14th amendment, Black males were given the vote by the 15th amendment.

African Americans voted and held office in many Southern states through the 1880s, but in the early 1890s, steps were taken to ensure subsequent “white supremacy.” The 15th Amendment had been carefully worded to maximize its chances of ratification. It didn't go so far as to grant the right to vote to all citizens regardless of race —instead, it barred states from denying suffrage based on race, opening a loophole for literacy, land ownership, or other requirements. It was a loophole that Southern states quickly exploited to effectively ban Black people from the polls.

Literacy tests for the vote, “grandfather clauses” excluding those whose ancestors had not voted in the 1860s, and other devices to disenfranchise African Americans were written into the laws of former Confederate states.

Social and economic segregation were added to Black America’s loss of political power. In 1896, the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson legalized “separate but equal” facilities for the races. For more than 50 years, the overwhelming majority of African American citizens were reduced to second-class citizenship under the “Jim Crow” segregation system.

During that time, African Americans sought to secure their rights and improve their position through organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) and the National Urban League, and through the individual efforts of reformers like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and A. Philip Randolph.

The most direct attack on the problem of African-American disfranchisement came in 1965. Prompted by reports of continuing discriminatory voting practices in many Southern states, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Congress to pass legislation “which will make it impossible to thwart the 15th amendment.” He reminded Congress that “we cannot have government for all the people until we first make certain it is government of and by all the people.”

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, extended in 1970, 1975, and 1982, abolished all remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorized federal supervision of voter registration where necessary. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the act involving federal oversight of voting rules in nine states.

Transcript

Fortieth Congress of the United States of America;At the third Session, Begun and held at the city of Washington, on Monday, the seventh day of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-eight.

A Resolution

Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Respresentatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, (two-thirds of both Houses concurring) that the following article be proposed to the legislature of the several States as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States which, when ratified by three-fourths of said legislatures shall be valid as part of the Constitution, namely:

Article XV.

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude—

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Schuyler Colfax

Speaker of the House of Representatives.

B.F. Wade

President of the Senate pro tempore.

Attent.ED McPherson

Clerk of House of Representatives.

Geo. C. Gorham

Secy of Senate U.S.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 299797

Full Citation: Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; 2/26/1869; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/fifteenth-amendment, April 19, 2024]Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1

Document

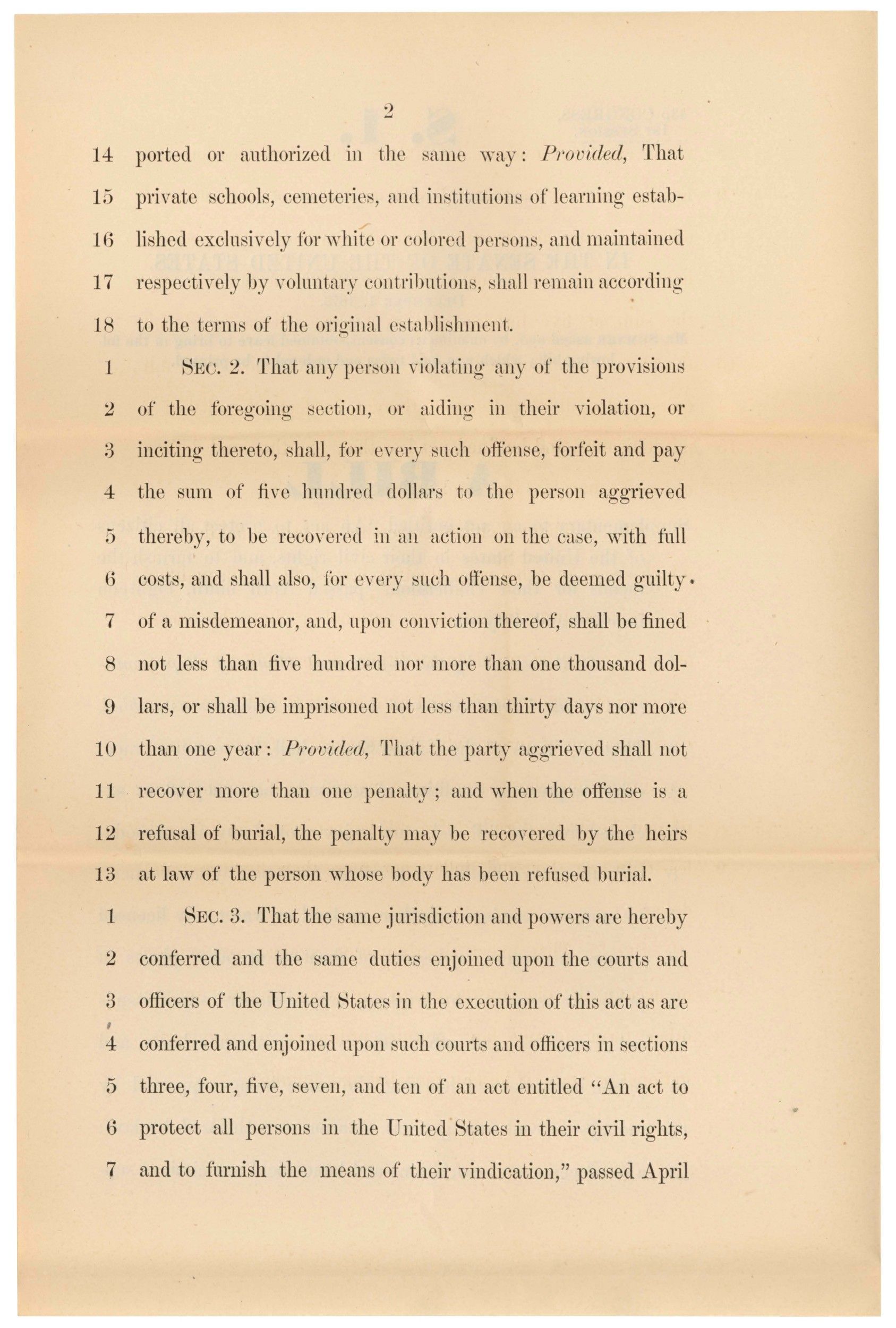

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

12/1/1873

There was a great divide over how far the Government should go to enforce the rights established by the 14th and 15th Amendments. The Civil Right Act of 1875, first proposed by Senator Charles Sumner in 1870, was an attempt to codify those rights.

Senator Sumner was the chief Radical Republican leader during Reconstruction and a vocal proponent of civil rights for freedmen. He introduced the version shown here to the Senate in 1873. It proposed to prohibit racial discrimination in public accommodations, such as hotels, theaters, transportation, and schools. He was so determined to see it pass that on his deathbed in 1874 he begged Frederick Douglass not to let it fail.

The bill that passed after much debate and revision in 1875 stated that all American citizens “shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement.” Prior to passage, Congress removed the clause which prohibited discrimination in public schools.

Senator Sumner was the chief Radical Republican leader during Reconstruction and a vocal proponent of civil rights for freedmen. He introduced the version shown here to the Senate in 1873. It proposed to prohibit racial discrimination in public accommodations, such as hotels, theaters, transportation, and schools. He was so determined to see it pass that on his deathbed in 1874 he begged Frederick Douglass not to let it fail.

The bill that passed after much debate and revision in 1875 stated that all American citizens “shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement.” Prior to passage, Congress removed the clause which prohibited discrimination in public schools.

Sumner, who died in 1874, did not live to celebrate the bill’s passage. Nor did he see its ultimate failure when, in 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives.

National Archives Identifier: 1986640

Full Citation: Sumner Civil Rights Bill; 12/1/1873; (HR43A-C1); Bills and Resolutions Originating in the Senate and Considered in the House, 1789 - 2003; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://docsteach.org/documents/document/sumner-civil-rights-bill, April 19, 2024]Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 1

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 2

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 3